Young Adult Archive

|

On this page:

◇ The Straight Road to Kylie by Nico Medina, reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons ◇ Hurt Go Happy by Ginny Rorby, reviewed by James Barrett-Morison ◇ Anatomy of a Boyfriend by Daria Snadowsky, reviewed by Jennifer Bartman ◇ Freak Show by James St. James, reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons ◇ Olivia Brophie and the Pearl of Tagelus by Christopher Tozier, reviewed by Louis K. Lowy |

This is the Young Adult Archive page. For more recent reviews, see the main young adult page.

|

|

The Straight Road to Kylie by Nico Medina

(Simon Pulse, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Paperback, 295 pp., $8.99, Ages 14 & up) Reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons |

The Straight Road to Kylie

Reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons When you get drunk, there’s always the possibility you’ll do something stupid, and we see the consequences of this in The Straight Road to Kylie by Nico Medina. The protagonist is seventeen-year-old Jonathan Parish who has too much to drink at his best friend’s party and has sex for the first time with an acquaintance, Alex. Most seventeen-year-old guys wouldn’t find this a problem, but in this case Alex is a girl, and Jonathan is gay. Since Alex isn’t very discrete, the word quickly gets out around Jonathan’s Winter Park, Florida high school that Jonathan isn’t gay, although he really is, and Laura, the richest, most beautiful, most popular girl in the high school strikes up a deal with him. He will pose as her boyfriend, and in exchange she will get him a ticket to London to see the Australian female singer he worships, Kylie Minogue. Laura says she is proposing this arrangement because Jonathan is the coolest guy in school now since he is very cute and has suddenly become heterosexual, and she needs to be with the coolest guy in order to maintain her reputation. Later we learn Laura has an ulterior motive, and the charade, of course, leads to disaster. As I read, I found Laura and Jonathan’s arrangement difficult to believe, but it wasn’t a problem because Jonathan’s honest observations, sense of humor and outrageous adventures were enough to keep me turning the pages. At first I thought Jonathan was a little flighty. All he had on his mind was sex, fashion, music and alcohol. But when I thought back to my priorities at age seventeen, the character seemed very realistic. Jonathan has an older model teenage-special car (a clunker with no A/C but a stereo that cranks) which he names “Aretha.” He has a part-time job at Target as a returns clerk, so you can imagine the joy of performing that job with a teenage hangover, which is played up wonderfully in the novel. He loves to sing and dance and dress up like Madonna. But his most endearing quality is his genuine affection for his female friends. There is Joanna who is, according to Jonathan, “a natural beauty” who “never gets the good guys.” Then there’s Shauna, who is “stacked,” but “super-bashful” until Jonathan gets her to let her hair down. And finally, there’s “wild-haired, gorgeous” Carrie, who smacks him on the ass when she introduces herself to him. While Jonathan seems to laugh his own problems off in the novel, he does witness these girls experiencing some genuine teenage angst. And he is their rock. Until he screws things up, that is. A fun aspect of this book is that it’s set in the Orlando area (where Medina grew up) and Jonathan and his friends make the most of the tourist town. Medina writes, International Drive is the Times Square of Orlando—an eyesore of tacky tourism, extended into a three-mile stretch of hotter-than-hell asphalt that runs from Sea World to Universal’s two theme parks. There’s a haunted house in the shape of a skull, an indoor skydiving wind tunnel, a huge water park, an outlet mall complex made up of seven buildings, go-kart tracks, tacky T-shirt emporiums, and the world’s largest Checkers. Jonathan and his friends love cruising International Drive with its “temples to tastelessness,” visiting a T-shirt-by-the-pound shop and indulging in a sundae at the McDonald’s with the world’s largest Play-Place.

Life in general for these characters seems to be a constant party. In fact, the characters have so much fun that I question the publisher’s recommendation that this book is for teens age fourteen and older. Instead, I suggest sixteen and up because there is detailed sexual content and casual use of alcohol and marijuana. In the end, since Jonathan tends to take things in stride, he doesn’t seem to experience any genuinely painful adolescent moments. The Straight Road to Kylie is not about Jonathan having to deal with being gay. His homosexuality is taken for granted, and Jonathan has a solid support system in his parents and friends. At a superficial level, Jonathan does examine his values, but the plot doesn’t present him with any difficult decisions to make. Deep introspection isn’t necessary to enjoy this book, though, because it’s a lot of fun just taking a ride around Orlando with these hilarious characters. Susan Jo Parsons is Publisher of The Florida Book Review. |

|

Hurt Go Happy by Ginny Rorby

(Starscape, Hardcover, 267 pp., $17.95) Reviewed by James Barrett-Morison |

Hurt Go Happy

Reviewed by James Barrett-Morison Hurt Go Happy, Ginny Rorby's second novel, is as much a gem as her first, Dolphin Sky. It follows the story of Joey, a deaf teenager, and her friendship with Dr. Charles Mansell and Sukari, his chimpanzee. What makes them friends is Sukari's ability to communicate through sign language. But Joey's mother does not want her to learn to sign due to Joey's family's troubled past. When Sukari is taken away and put under animal testing, Joey must confront her mother—and her own fears—to save her chimpanzee friend. Hurt Go Happy is packed with suspense, humor and emotion. It is a real page-turner. The scenes in the testing facility are poignant and moving, and will make your heart race. At every turn, you want to know what the next step will be. Even in the parts not actively suspenseful, Rorby still leaves you wondering what happens next. One of the book's strongest points is its emotion. The story confronts the problems of discrimination against the deaf, child abuse, and animal cruelty through well-crafted, realistic characters. In the dedication, Rorby says that her inspiration came from a girl named Belinda she knew when she was working at a day-care center, who was abused and beaten by her mother, and from a homeless dog that had taken up residence near her home in Miami and had to be put down. The author's emotions about cruelty towards animals and humans alike shine through in the story. Although it is obvious that Rorby is greatly opposed to child abuse and animal testing, it does not overwhelm the story as she weaves these themes in with beautiful but simple language. When she is rescuing Sukari in the lab, she says, Though this room had recently been washed down with the black rubber fire hoses that were dripping at each end of the gray concrete room, it still reeked. Joey knew the smell – she'd smelled it on her mother and on herself. The room was saturated with an odor no Clorox could cover – the stench of fear. Joey's mother once had a suede coat with a fox collar... Now, crossing this room, she imagined the fox, whose fur had made that collar, one foot clamped in a steel-jaw trap, frantically trying to gnaw its own leg off. How did they ever rid the fur of that smell of terror? The book is punctuated by glimmers of humor that keep it lively and away from being a depressing tome. Small anecdotes about Joey's teen friends' ups and downs liven up the story well, but don't overly distract from the main storyline.

In many young adult novels, it seems that the characters are either good or bad. A really good young adult novel stands out because of its complex characters. A good example of this is J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series. Another is Hurt Go Happy, in which of the characters have both a good and a bad side. Ruth, Joey's mother, restrains her daughter from learning sign language, but for most of the book, we don't know if her motives are positive or ulterior. Minor characters also are not quite what they seem at first. Lynn, Charles Mansell's daughter, seems to be very nice at the beginning, but her actions eventually show that she doesn't really care about Sukari's well-being. Even Sukari herself has her good and bad sides—she is kind and gentle, except that she hates other chimpanzees! This book is of definite interest to Florida readers. Rorby lived in Florida while she worked as a flight attendant and got a graduate degree in writing. South Florida is an important part of the story, especially the ending – for the last quarter of the book, Miami is the final destination, the ultimate goal. After you've completed the book, it will stay with you. Today at the airport I saw two people speaking to each other in sign language, and the first thing I thought of was Hurt Go Happy. But it wasn't just a passing thought—I was interested in who those people were, and what it was like for them. Rorby puts a human face on this group which is normally ignored by the general hearing public. This book is obviously of interest to those involved with its themes—the deaf, animal language, or animal rights—and for the target age group, those in their teens. But this book is for more that just the obvious readers. Adults as well as teens will find this book extremely witty, enthralling and moving. Also, if you have no idea about one of the main themes, Rorby makes it easily approachable. For those with no clue about sign language, there is a handy sign language alphabet page at the back of the book. For those not familiar with animal rights, Rorby makes the issue both approachable and enthralling. This is a highly recommended read for those of all age groups and beliefs, as it can reach—and touch—everyone. James Barrett-Morison is a junior at Ransom Everglades School in Coconut Grove, Florida. He is also a contributing editor at The Florida Book Review. |

|

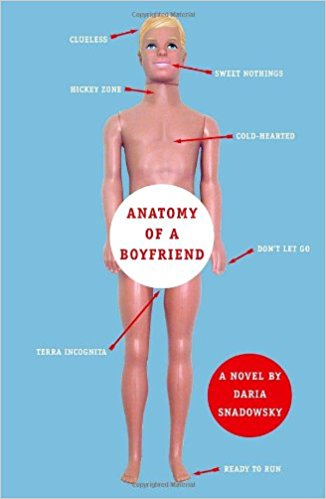

Anatomy of a Boyfriend by Daria Snadowsky

(Delacorte Books for Young Readers, Hardcover, 272 pp., $16.99) Reviewed by Jennifer Bartman |

Anatomy of a Boyfriend

Reviewed by Jennifer Bartman It’s unfortunate that including frank description of body parts and everyday sex acts should be considered daring in young adult fiction, but thanks to American prudery and those abstinence-only-education types, it is. For some adolescents, Anatomy of a Boyfriend will be an exciting glimpse into the world of sexual experience. For others, especially those who are looking for greater openness about other aspects of teen life, as well, the story may be lacking. The novel follows the course of seventeen-year-old protagonist Dominique’s first romantic relationship with Wesley, a fellow high-school senior, and travels with them into college the following school year. This teen love story includes descriptions of Dom and Wes’s experimentations with, among other thing, manual stimulation, oral sex and vaginal intercourse. The novel is written in first person, so the emotional and sexual details of the relationship are delivered in Dominique’s voice. She possesses a sometimes annoying mixture of naiveté and knowledge, which perhaps helps to build her authenticity as a teenager. She plans on becoming a doctor and reads Grey’s Anatomy for fun, so she knows the proper terms for body parts and functions; however, at seventeen, she has never seen a penis outside a medical text, much less actually touched one. When she does touch her boyfriend’s genitals for the first time, she explains, “It’s cool how the skin can move up and down a little, like it’s not really attached to whatever’s underneath.” But when he does not ejaculate after a few minutes of this, she wonders, “Do you have to do something special to finish a hand job? I don’t remember any grand finale techniques in the sex encyclopedia.” I imagine it would be fun for the adolescent who identifies with Dom to read many of her own sexual questions answered over the course of the novel. I found elements of Dom’s sexual experiences to be especially authentic and amusing: Her first time having intercourse only lasts a few seconds. Her adolescent boyfriend is unable to help her reach orgasm. She worries about farting during sex. Though the novel has many such energetic and amusing moments, I think some adolescents will have trouble identifying with the rest of Dom’s story. She seems to have very little conflict in her life until the end of the novel, and for a teenager, she has very little angst. When she fights with her loving parents, they make up almost immediately. Her boyfriend’s family adores her, too, and do so as soon as they meet her. She attends a small private school where her mother is a teacher, and she gets good grades. Her loving father is the chief of police in her beautiful Florida town. She is part of a middle-class family, who spend weekends fishing together. If I were an adolescent reading the book—well, actually, when I was adolescent, I probably wouldn’t have read the book. Or at least the whole thing. For starters, I would have been completely embarrassed holding it in the bookstore for too long, because the cover is basically a naked Ken doll with a white circle covering the plastic lump that represents his penis. Second, I would have thought Dom was a stupid goody-two-shoes who needed to get a life and a clue. I would have skimmed over the “boring stuff” about Dom’s oh-so-white-bread experiences, reading the sex parts and skipping to the sections where conflict actually takes place. Adolescents are interested in conflict, and I know very few who have lives as sheltered or ideal as Dom’s. A lot of messy, scary and complicated things happen to adolescents, and although a few messy, complicated things are addressed in Anatomy of a Boyfriend, I was left wondering if Dom experiences were out of the ordinary or if mine were. When I was a teenager, my friends and I knew a hell of a lot more about sex than Dom does in the book. We may not have known the exact chemical make-up of semen (which Dom can state by heart), but we started experimenting much younger then she did, and we had at least seen a little bit of porn or watched Real Sex or read some erotica by seventeen. Furthermore, girls we knew were sexually harassed, raped, pregnant, into S&M, clandestinely dating much older men or other girls, and getting into all kinds of sexual stuff on the internet. Every single girl I knew had some sort of body-related issue or shame. How could they not in our culture? However, none of these issues seem to exist in Dom’s world. For the majority of the novel, her biggest problem seems to be that she is constantly falling down—literally—only to be helped up by her boyfriend or loving family and friends. Perhaps I am being too hard on the protagonist, and on the story. Maybe the publisher would allow explicit teen sex only in this otherwise tame setting, and the author submitted to writing an otherwise G-rated world. Also, some difficult, although entirely ordinary, things do happen in Dom’s life at the end of the story. Perhaps there are many girls like Dom—an only child who goes to small private school and has only one friend with whom she discusses relationships—for whom this novel would not only be riveting, but also really informative and sexy. To them, I say, read the book immediately, and then go ahead and Google “dental dam” since, although Dom knows where to buy one, you have probably never even heard of it. And don’t worry, unlike Dom, it probably won’t hurt you the first eleven times you have vaginal intercourse. For other adolescents, however embarrassing the cover and annoying the protagonist, the book does involve honest descriptions of sex acts with which you may be currently experimenting. More importantly, this novel turns out to explore the value of masturbation, and, if you are an adolescent girl, it is very likely that no one talks to you about masturbation at all. If Anatomy of a Boyfriend convinces even a few adolescent girls to learn to enjoy, rather than scorn, their own bodies, then it is worth its weight in “personal massagers” like the one Dom receives from her best friend Amy toward the end of the book. Jennifer Bartman is an MFA candidate at Florida International University. |

|

Freak Show by James St. James

(Hardcover, Dutton Juvenile, 224 pp., $18.99, 15 and up) Reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons |

Freak Show

Reviewed by Susan Jo Parsons If you thought your adolescence sucked, and that it was so hard to fit in because of some little quirk or flaw you may have had, consider Billy Bloom’s dilemma in James St. James’ Freak Show. Billy is a seventeen-year-old New Jersey drag queen newly transplanted to Florida. He has been passed on to his father by his mother, who “couldn’t take another day,” so Billy moves into his father’s mansion on a Fort Lauderdale waterway. His dad enrolls him in an excusive prep school which is located at the edge of a swamp. Dwight D. Eisenhower Academy, according to Billy, is populated by “A seething, writhing army of upper-crusties… Stepford teens in full preen… your choice of blond or blonder… the WASP nest.” This nest of “WASPS,” “Evil Cheerleaders,” “Junior Klansmen,” “Muffy Mafias,” “Bubba Gumps,” “Bible Belles” and “Debutaunters” have never seen the likes of Billy. Conservatively, Billy dresses as a pirate for his first day at school. No dress, no makeup. Well, OK, the remnants of mascara. And just a little lip gloss. And a crimson sash. And so the disgusted looks, the cruel remarks, the spitballs, the little punches, the kicks from behind and “ballistic weaponry” begin (“rubber bands…pencils, pens…maxi pads…ketchup in a condom…large and small rocks…dog shit, bird shit, hamster shit”…). The Fort Lauderdale Billy lives in is a little different from the one I call home. The teens I have encountered here seem pretty tolerant. And most teachers I know don’t overlook gay bashing in the classroom—even if the bashers are star members of the school’s football team. But it’s fiction, and the character is prone to hyperbole, so I willingly tossed my Fort Lauderdale aside for Billy’s for a while. The tauntings rage on. A group of Bible Belles wait for Billy in the mornings chanting in unison, “If a Man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.” And St. James writes that “The jackals are circling…The violence is now flagrant, even casual. Bruises are commonplace. As is blood.” Billy finds one ally, however, a girl he refers to as “Blah-Blah-Blah.” He doesn’t bother to learn her name because, after all, she will only speak to him behind the bookshelf in the library when no one is looking. She is simply a source of gossip for him, and later a “sidekick” for one of Billy’s schemes, and he apparently doesn’t appreciate her risking her life to befriend him. But I forgive Billy because he has a troubled life. He slowly reveals that his mother is not quite up for motherhood, and his father is mostly absent. Billy suffers from self-loathing and on particularly bad days he hides in a locker located in his bedroom, or in between the folds of a sofa bed in a guest room. He finally dares to appear at school in full drag after realizing that they all hate him anyhow, so what the heck. He’s not going to give into them. But his outrageous outfit (as a “Radioactive Swamp Zombie”) ignites the worst violence to date in members of the football team, who he refers to as the “Backseat Boys” since they sit in the back of his Biology class. However, amazingly, one of the Backseat Boys, Flip, leaves the ranks and rushes to Billy’s rescue during the severe beating. So Billy falls in love. Who could blame him? Flip is a “Bambi-eyed pretty boy,” with “white-blond hair like Icelandic royalty,” and “bright green eyes, like kryptonite.” Flossie, Billy’s African-American maid and chauffeur, adds that Flip “doesn’t have the brains God gave a squirrel.” Billy struggles to maintain the friendship with Flip, happy just to smell his sweet scent and see his golden hairs up close even if Flip is heterosexual and off limits. After some successes and some setbacks, Billy decides to go for it—he campaigns for Homecoming Queen. The competition is stiff as he runs against a Bible Belle who has been campaigning since the 7th grade. The joy of this book is when Billy goes into full drag, which is often. Take, for example “The Application of the Maquillage:” Your face? White! Yes—Look At Me White…The foundation must be thick and oily—the worse for your skin, the better it will look. Pile on pound after pound of it. Slather it on with a spatula—it should be two or three inches deep. I want to see bird tracks in there by morning…Your lips—a slash! A gash of red, blood red—raw like a wound…On the cheeks? Around the eyes? Perhaps a little color? Technicolor, darling! And when Billy selects, or makes, his dresses it’s a day long process. Or a week’s process. There is the Zelda Fitzgerald-After-the-Fire look. And the Super Freak. There is the application of various fruit to wigs or “a hibiscus to the ear.” Everything has to be PERFECT!

The book is a quick read since it is broken up into little chapters and has lots of white space between the paragraphs. St. James’ demonstrates the character’s exuberance BY HAVING HIM SHOUT A LOT ABOUT HOW FABULOUS OR HORRIFYING SOMETHING IS!! Another fun aspect of the book is when the narrator admits he is totally unreliable. For example, about half way through the book, Billy stops all the action to admit that he lied about what really went on between him and his mother back in New Jersey. The book has a wild climax, with the whole school and the press present. In the end, while Billy is a bit prone to exaggeration, the book should appeal to anyone who is going through, or has experienced those painful ups and downs of adolescence. I just wish he had been a little nicer to Blah-Blah-Blah. Susan Jo Parsons is Publisher of The Florida Book Review |

|

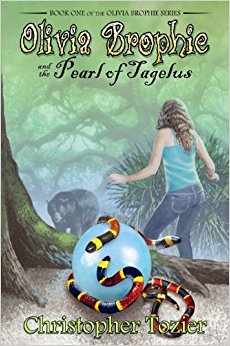

Olivia Brophie and the Pearl of Tagelus by Christopher Tozier

(Pineapple Press, Paperback, 208 pp., $12.95) Reviewed by Louis K. Lowy |

Olivia Brophie and the Pearl of Tagelus

Reviewed by Louis K. Lowy Olivia has several problems. She hasn’t heard from her mother, who is a US soldier fighting in Iraq. Her father appears to no long want her or her younger brother, Gnat. Her father has arranged for them to move away from their house in Wisconsin to the scrublands of Lyonia, Florida, to live with eccentric Aunt and Uncle Milligan. And, oh yeah, Olivia’s received for her tenth birthday a red barrette that has a strange influence on animals. This only begins to scratch the surface of Chrisotopher Tozier’s Book One of the Olivia Brophie series Olivia Brophie and the Pearl of Tagelus. It is a rousing, Tom Sawyer on steroids adventure that involves—among others—an ancient underground city, a witch, an evil cult, a lovable echinoid named Squirt, frogs who write in ancient Arabic, and a sphere that controls the laws of nature. Though Tozier’s tale is a non-stop Tilt-a-whirl, it is also the story of Olivia trying to cope with her mother’s absence and with a father who has apparently abandoned her. It also traces her journey from immaturity to maturity, where she learns to cope with the burden of enormous power and the responsibility that comes with it. We get an inkling of both of these in the following short passages. The first—following her battle with the witch, Miss Rinkle—deals with her desire for parental love. Olivia walked out onto the ice. One thing she did remember from living in Wisconsin was how to walk efficiently on ice. She looked down at the top of Miss Rinkle’s head. It occurred to her just how much she had wanted Miss Rinkle to like her. How nice it was to have a woman care for her and tell her how smart she was. Later, as she is walking through the woods, we get a sense of the weight she feels pressing upon her.

Long gone was the little girl who ran into the woods wearing flip-flops and harassed an innocent tortoise. Long gone was the little girl dreaming of becoming a ballerina. . . Everyone was depending on her. Tozier was wise to include Olivia’s intimate struggles because they provide depth to the larger, grandiose battle, and ultimately they are the reason we want to root for her.

Another secret weapon in Tozier’s arsenal is Gnat, Olivia’s six-year-old video game freak of a brother. He analyzes everything in player terms: his Aunt is Mothership, he is Gnat, Power Soldier Level Six, and when he hits the back of another boy’s head with acorns, he refers to them as bonus points. He is funny, realistic, and likeable. Olivia treats him like a dorky younger sibling. Beneath her sarcasm and Gnat’s dependence on Olivia, Tozier reveals their affection for each other. Olivia Brophie and the Pearl of Tagelus is written for middle-graders. It is fast paced, larger than life and filled with lessons on Florida habitat, above and below the ground. It is the first in a series, and by the end of this initial offering Olivia is in even more trouble than she was throughout the previous 214 pages. Tighten your harness and hold on, the carnival ride is about to crank into overdrive. Louis K. Lowy, a former firefighter, is the recipient of a Florida Individual Artist Fellowship. His work has appeared in Coral Living Magazine, New Plains Review, Merge and The MacGuffin, among others. His sci-fi novel Die Laughing was released in August 2011. Contact him at his website www.louisklowy.com. |