Poetry

On this page:

◇ Heat Seekers by Steve Lambert, reviewed by Connor Nelson

◇ Mud Song by Terry Ann Thaxton, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ American Sentencing by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ The Treasures That Prevail by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ A History of the Unmarried by Stephen S. Mills, reviewed by Cathleen Chambless

◇ Awaiting Your Impossibilities by Donald Morrill, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Brie Season by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ Suicide by Jaguar by Dave Landsberger, reviewed by Ariel Francisco

◇ Prayer of Confession by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The Road to Emmaus by Spencer Reece, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ Lucky Bones by Peter Meinke, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The Lame God by M.B. McLatchey, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Systems of Vanishing by Michael Hettich, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Bachelor Pad by Stephen Kampa, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ On the Street of Divine Love by Barbara Hamby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ A Wilderness of Monkeys by David Kirby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The War on Pants by Kristine Snodgrass, reviewed by Leslie Taylor

◇ Landscaping for Wildlife by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ The Biscuit Joint by David Kirby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Bearable Weight by Michael Cleary, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ He Do the Gay Man in Different Voices by Stephen S. Mills, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

◇ Brackish by Jeff Newberry, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ An Elephant's Memory of Blizzards by Neil de la Flor, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

◇ Blowout by Denise Duhamel, reviewed by James Allen Hall

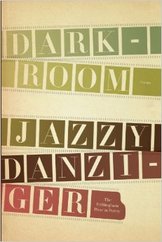

◇ Darkroom by Jazzy Danziger, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

◇ Heat Seekers by Steve Lambert, reviewed by Connor Nelson

◇ Mud Song by Terry Ann Thaxton, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ American Sentencing by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ The Treasures That Prevail by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ A History of the Unmarried by Stephen S. Mills, reviewed by Cathleen Chambless

◇ Awaiting Your Impossibilities by Donald Morrill, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Brie Season by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Bonnie Losak

◇ Suicide by Jaguar by Dave Landsberger, reviewed by Ariel Francisco

◇ Prayer of Confession by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The Road to Emmaus by Spencer Reece, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ Lucky Bones by Peter Meinke, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The Lame God by M.B. McLatchey, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Systems of Vanishing by Michael Hettich, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Bachelor Pad by Stephen Kampa, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ On the Street of Divine Love by Barbara Hamby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ A Wilderness of Monkeys by David Kirby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ The War on Pants by Kristine Snodgrass, reviewed by Leslie Taylor

◇ Landscaping for Wildlife by Jen Karetnick, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ The Biscuit Joint by David Kirby, reviewed by Marci Calabretta

◇ Bearable Weight by Michael Cleary, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ He Do the Gay Man in Different Voices by Stephen S. Mills, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

◇ Brackish by Jeff Newberry, reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello

◇ An Elephant's Memory of Blizzards by Neil de la Flor, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

◇ Blowout by Denise Duhamel, reviewed by James Allen Hall

◇ Darkroom by Jazzy Danziger, reviewed by Julie Marie Wade

|

Heat Seekers by Steve Lambert

(Cherry Grove Collections, 102 pages, $19.00) Reviewed by Connor Nelson |

Heat Seekers by Steve Lambert

Reviewed by Connor Nelson If you open Steve Lambert’s Heat Seekers in bed, at a coffee shop, or in your private study, you’ll soon find yourself reading through sunglass lenses, sunscreen smudging the cover, on the back of a Harley headed down “promiscuous, gauche, past-her-prime US-1.” Heat Seekers is the dirt underneath the fingernail of Florida—people you look past at the gas station, shady street corner business you pretend not to notice, the insect comfortable on your motel room ceiling, death—and, like a Floridian, these poems don’t mind showing a little skin. The Florida backdrop of this collection is harsh and, to a local, familiar. “The day is sun-shattered… Sweat is everywhere,” in the title poem, and in “The Worst Coast,” the sun is “sociopathic.” Meanwhile the voice remains casual. Bare, dirty realities are observed and retold in clean, consistently-relaxed syntax, perhaps an echo of Floridian nonchalance. We are “devotees of the prosaic,” the speaker informs us in “Saint You,” linguistically keeping cool no matter how hot and humid it gets. Like a camera filming a reality show, this language focuses on “life and its sincere participants,” such as those “At the Shell,” where characters are quickly and sharply drawn: “A serious young man / gases up his / perversely clean 4x4.” Just feet away: Two beautiful This comedic and irony-seeking eye draws the reader along. Each time I turned the page, I was eager to meet whoever was being observed, and I was delighted upon being introduced to the Elvis impersonator who may have been “Elvis disguised as himself,” in “Graceland.”

But time does not give up in Lambert’s world and fear is at the core of many of these poems. When “Desperado” begins “A week before chemo,” we deduce, with knowledge from other poems, that the patient is the speaker’s father. Having romanticized the past before, now the speaker, “bullied” by “the largeness of death’s reality,” looks forward rather than back: . . . Four months This voice’s ease tricked me more than once, setting me up to think life was simple and fun. The speaker describes his mother in “Calamity Jane” as

she whirls through her living room, Then an unexpected word tears the veil of simplicity: “How / graceful my fatherless mother,” revealing anguish and abandonment, the complex history that underlies most anything, the part I often forget to consider. With the swiftness of a tropical afternoon shower, these reminders of death are scattered across the collection, then quickly replaced with the calmness we are used to: “How // gracefully she suffers the graceless.”

In lines like these the language comes out of hiding, calling attention to itself, at times using the repetition of a word, as with “grace,” to pinpoint irony. This self-awareness translates into subtle humor as well: “A lean man leans / into the mouth of a blocked Dodge Charger,” in “The Decline.” Toward the end of the collection in “Something Thereabouts,” the speaker discusses the style of his observations, calling it “not of the heart of things, / but around it.” Like a magician revealing the secret to his trick, the speaker confesses: “I don’t always look deep, / but I usually look long,” arguing that in poetry and life, “Surfaces are sometimes enough.” Heat Seekers enriched my surroundings, tuned my ears to the details that make up the “humming of being.” Lambert’s poems reassured me that it’s possible to be afraid of death and still laugh; it’s perhaps essential. They will complement your summer and leave you with “a line to carry along on a scrap of paper / in the back pocket of your mind: / a small worthwhile thing.” Connor Nelson lives and writes in South Florida. |

|

Mud Song by Terry Ann Thaxton

(Truman State University Press, 80 pp., $18.00) Reviewed by Bonnie Losak |

Mud Song by Terry Ann Thaxton

Reviewed by Bonnie Losak Terry Ann Thaxton is a fifth-generation Floridian, an anomaly in Florida, home to so many who have arrived here in search of an escape, some from cold winters, others from the cold reality of poverty and despair that have come to define their homelands. Her third poetry collection, Mud Song, focuses on Florida landscape and experience in a way that calls to both those who live here and those who reside elsewhere. When reading Mud Song, don’t skip over the prelude, “History of America,” which sets the tone. Here, the speaker describes the lot of women traveling to the new world: On the boat the men drank whatever the women poured The poem grows darker in the next stanza:

Women sharpened knives The past inches forward in measured increments as the poem moves toward its conclusion:

My sixth-grade teacher taped the evolution poster The postlude, “Terry Reminds Herself How to Live,” also serves an important function in Mud Song. Here, the speaker admonishes herself that: “When your mother’s photo stares at you from the basket,/remind her that she is dead.” Other directives in the poem appear more forgiving than reproving in nature, such as: “Take recyclables out only on weeks you feel like it, and,/Jesus Christ, remember your name.” My favorite lines in this poem give the speaker permission to err in ways, it seems, she already has: “Leave your notebook/with lists and lists of things to do/in a public bathroom/an hour from your house.” The speaker’s mother reappears at the end: “Forget the gardenia you tried to grow/in memory of your mother; use the dirt from the pot/for another, more willing, plant.”

An uneven relationship with family members is a theme in many of the poems of Mud Song. In “Letter of Forgiveness” Thaxton writes, “Once I threw a green rock into the meadow. It knocked my mother out./Once, before the sky went black, I held my father’s drill like a gun.” As we near the end, though, the speaker reveals what she has learned about her mother, “I didn’t know she was afraid of losing me, of losing/all her children to the man she married, the man she hated.” A mother’s fear of loss returns as a theme in “Cold War”: Why didn’t they take my son away from me? “Walk or Fly, but Do Not Look Down” also speaks to fear, but this piece allows a glimpse into activities that do not spark dread in the speaker:

I’ve never been afraid of climbing trees. Sleeping with the windows closed and the air-conditioner on year-round may be a distinctly Floridian experience, as are many of the other concerns captured in Thaxton’s poems —Cuban refugees recently arrived (“Afternoon Forecast”), sinkholes that swallow homes (“The Truth About Florida”), and alligators sunning in one’s flower bed (“Alligators”). Somehow, though, the poems are larger than the land from which they arise. They evoke not only Florida, but also the universal refrain of loss, regret, and survival.

Bonnie Losak is an attorney practicing in Miami, Florida, and an MFA candidate at FIU. She lives and writes in Miami Beach. Her work has been published in Fiction Southeast and Hippocampus Magazine. |

|

American Sentencing

by Jen Karetnick (Winter Goose Publishing, 100 pp, $10.99) Reviewed by Bonnie Losak |

American Sentencing

Reviewed by Bonnie Losak In American Sentencing, Jen Karetnick has penned a poetry collection that is focused on and dedicated to those who suffer from chronic, invisible illnesses. As someone who fits neatly within this vast grouping, I applaud both Karetnick’s concept and its execution. The poems in American Sentencing never stray far from Karetnick’s South Florida roots. Thus, in “Self-Diagnosis: Tropical Depression” Karetnick gathers her metaphors from the sea. Referring to “hemmed-in thoughts” she asks, “What mullet/ could leap consistently through such endless/pointillism and still know where to land? /What manatee could find space to surface,/what dolphin air to breathe?” As for the subject of the poem, she “swim[s] with hands/ready to meet door jamb, feet to bed post.” As is often the case with Karetnick’s work, the concluding couplet in “Self-Diagnosis: Tropical Depression” is the most compelling: “There is little point to knowing up, down./On days like this, it’s always sideways that I drown.” Karetnick moves from depression to another invisible illness in “For Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis.” In this poem, Karetnick writes of the conflicts inherent in relying on daily doses of medicine to maintain one’s strength, one’s sanity, or indeed, one’s life. The last stanza of “For Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis” reflects the dueling sentiments confronted by those who are medicine-dependent: “I have no limits to argue with–/I can eat ice cream, pay bills, paint walls-/as long as I follow this prescripted path,/swallow forever the exact same oath.” Many of the poems in American Sentencing seethe with the suffering of women. Thus, in “Labor” Karetnick describes a “return to flames and spin as cramps/sweat under my skin and I unlock/the damper of my diaphragm, loosen/and harden in turn to breathe, breathe, /breathe this body into being.” In “Night Sweats,” Karetnick speaks to salty secretions that “flood/you in the neighborhood of sleep/where once-solid canyons of breasts,/hips, knees, parched from breath, west of age,/have slipped, begun to crack.” According to Karetnick, this nocturnal heat is “teaching you reversal, how to tread betrayal, ride luck/before lightning strikes, bringing rains.” Along with illness, death and decay figure prominently in American Sentencing. In “Will, Power,” Karetnick considers the process of bequeathing one’s belongings to those that remain behind. In this poem, the speaker leaves “to no one specific/and none intended/the white spaces that used to be words.” She further grants, “a governor’s pardon/for my natural killer cells,/disorganized, defeated,/deserting the front lines.” And, finally, in the last line of the poem, the bequest is simple and complete: “no more witnesses.” The poems in American Sentencing are not all about weighty issues, though. “Women on the Verge Discuss Viagra” begins with the etymology of the word stamina: “From the Latin stamen,/ meaning thread of woven cloth.” It continues with a query as to whether there might be, in addition to Viagra, “a pill to make them remember/to take out the garbage or mow the lawn?” The poem concludes on a humorous note, “Or better: to spark conversational vigor./No chance of that? Then don’t bring it on./This is the last thing, the last thing we want.” Whether playful or grim, the poems in American Sentencing are open and insightful. Karetnick is skilled at taking ordinary emotions and experiences and buoying them with striking images to create nuanced works. In American Sentencing, she takes this a step further by commingling themes of unseen diseases with unmet expectations and untimely death. A difficult trio, but by meeting them head-on, Karetnick manages to succeed. Bonnie Losak is an attorney practicing in Miami, Florida, and an MFA candidate at FIU. She lives and writes in Miami Beach. Her work has been published in Fiction Southeast and Hippocampus Magazine. |

|

The Treasures That Prevail by Jen Karetnick

(Whitepoint Press, Paperback, 117pp., $15.00) Reviewed by Bonnie Losak |

The Treasures That Prevail

Reviewed by Bonnie Losak Jen Karetnick’s new poetry collection The Treasures That Prevail is a primer on Miami for those who don’t know the city, and a deft, discerning reminder, for those who do. Although billed as a book about the effects of climate change, I didn’t find The Treasures That Prevail to be limited to this one subject. Instead, the poems in this collection explore such varied subjects as PTSD (“Fatigue of Blades”), the TSA (“Security Guidelines”), and terrorist threats (“Chatter”). If you read The Treasures That Prevail (and you should), read it the way I learned to only the second time ‘round—with a pinky finger marking the endnotes, for easy reference. Not only do these endnotes serve as a quick translation guide for the often obscure text message abbreviations in “Dear YKW,” but they also provide source information for the many “found” poems in this collection, rendering these poems infinitely more accessible. “Rough Diamond Fib” is one of the poems that I was ready to pass over as inscrutable until I located the endnotes. According to the notes, this poem was “found” in a 2014 Miami Herald newspaper article with the headline, “Florida clerk who mistook body for mannequin fired.” The headline alone is enough to transport the poem from the realm of enigma to an apt and vivid recitation of life in Miami, a place where tragedy and comedy often journey together. Another found poem, “Home of the R.I.P. T-Shirts,” is easier to grasp, even without the assistance of the endnotes. The notes, though, do assist by informing the reader that this poem was also “found” in a 2014 Miami Herald article, this one with the headline, “Friends and families of young, black homicide victims use T-shirts to mourn loss.” Karetnick begins “Home of the R.I.P. T-Shirts,” by introducing her readers to a T-shirt booth located in a gritty pocket of Liberty City, Karetnick then describes the sharp uptick in business that occurs at this booth, “[w]hen a well-known dope boy is murdered.”According to Karetnick, the grief-stricken come to the T-shirt booth, to cast

their loss on standard tees Karetnick captures the inadequacy of the T-shirt booth as an agent of change in a powerful final couplet:

Here, designers are archivists of death “Handcrafted,” also deals with imprinting one’s loss on a tactile surface, this time the body itself. In “Handcrafted,” Karetnick likens the work of a tattoo artist in Midtown Miami, to, “a fisherman scaling his catch.” She skillfully links the physical experience of having ink etched on one’s body with the emotional loss sought to be memorialized:

I separate myself from the buzz As “Handcrafted” makes clear, the success of The Treasures That Prevail lies in Karetnick’s ability to imbue the poems in this collection with an emotional resonance that stretches outside the City of Miami and beyond the subject of climate change, to encompass such everyday human emotions as loss, longing, and fear.

Bonnie Losak is an attorney practicing in Miami, Florida, and an MFA candidate at FIU. She lives and writes in Miami Beach. Her work has been published in Fiction Southeast and Hippocampus Magazine. |

|

A History of the Unmarried by Stephen S. Mills

(Sibling Rivalry Press, paper, 92 pp. $14.95) Reviewed by Cathleen Chambless |

A History of the Unmarried

Reviewed by Cathleen Chambless A History of the Unmarried is a dynamic and unapologetically queer collection of poetry that examines the definition of marriage in a heteronormative society and what it is like to be in a relationship that generally perplexes and, at times, enrages said society. Mills writes about a period of change, beginning when only a few select states affirmed couples’ existences by deeming them worthy of that simple word “marriage.” During some of it he was living in Tallahassee and Orlando, years before same-sex marriage became legal in Florida in January 2015. What does it mean to be unmarried only because homophobic America will not allow it? What does it mean to have your relationship called “domestic partnership” solely because it makes straight people more comfortable? What does it mean to have those arguing for your right to marry cite heteronormative standards as the reason you deserve this title, even though you are not heterosexual? Mills answers these questions, while raising more, in A History of the Unmarried. In autobiographical narrative poems Mills portrays his ten-year relationship with his husband, Dustin. Mills by no means caters to a potential straight audience by “toning down the gayness,” which many of us have been asked or forced to do. One of my favorite poems in this collection is “Holding Hands Outside a Pro-Family Rally With My Seed Inside You.” In fact, I cannot tell which act is of greater political importance, Mills and Dustin being present to protest against this pro-family rally, or the existence of this poem. Why is that? Because Mills does not shy away from the fact of how much he loves to cum inside of his husband’s ass. In fact, he successfully illustrates how downright beautiful this sexual action is to him: I doubt they would call this love, I also appreciated how Mills tackles the issue of homonormativity. In “Obama Says Same-Sex Couples Should be Allowed to Marry, May 2012,” Mills quotes Obama saying, “I think about my own staff who are in incredibly committed monogamous relationships, same-sex relationships, who are raising kids together” as the epigraph to the sex poem that follows. While Mills is married to Dustin, they are not monogamous. They are polyamourous, and this isn’t the only poem in the book that describes their sexcapades with other men. This one begins with a threesome that ends with two, Dustin and Stephen, in bed, and then Mills describes a typical domestic scene: Dustin buys groceries, Stephen cooks the dinner, they watch Seinfeld together, make love and fall asleep, their bodies “falling into familiar rhythms.” Is this not a portrait of a marriage?

A History of the Unmarried also includes odes to Jackson Pollock and Sylvia Plath, as well as excerpts about proper “housewife etiquette” from a 1950s textbook. I am partial to the way Mills’ inserts these to skillfully expose the layers in our society and our personal lives. We may laugh at them now, but there was a time when these texts were taken quite seriously. They serve as hard evidence of the heterosexism, patriarchy, and heteronormative values in American culture that have continued to thrive in the present, affecting the current definition of marriage. And Mills’ selection and placement of them lets him queerify one of the more sickening artifacts of the heteronormative marriage value system. For example, the first Housewife Etiquette Rule, which appears before Mills’ first poem dedicated solely to Dustin, reads in part: “. . . He wants something nice to look at when he comes home. He deserves it. Be gay and interested.” A History of the Unmarried stirs ingredients from multiple eras into a cocktail of the present garnished with a defiant queer parasol. Mills’ first book, He Do the Gay Man in Different Voices, won the Lambda Literary Award in Gay Men’s Poetry. This collection is undoubtedly an important piece of queer history, and queer literary history. Cathleen Chambless is from Miami, Florida. A poet, visual artist, and activist, she graduated with her MFA in poetry from FIU. She facilitates popular education based anti-oppression workshops with Miami's grassroots organization Seed 305. Her work has appeared in MPC's 10 Cent Journal, the anthology A Touch of Saccharine, the anthology Storm Cycle 2014, The Electronic Encyclopedia of Experimental Literature, Jai-Alai, and The Mind[Less] Muse. She co-authors a queer/feminist zine called Phallacies. |

|

Awaiting Your Impossibilities by Donald Morrill

(Anhinga Press, Paperback, 80 pages, $20) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

Awaiting Your Impossibilities

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta Look upon bitterness, that man sleeping in a dry well. He dreams he's an oasis and you a train of nomads lined up to drink from his hands. I had never heard of Donald Morrill before--knew nothing of his other two books of poetry and four books of nonfiction, nor that he is the Dana Professor of English at the University of Tampa--but as soon as I picked up his latest collection, with its plain white cover and peculiarly horizontal book layout, I knew this was not a book about which conclusions could easily be drawn. These are poems of long, cadenced lines that bring the reader in for questioning:

Whose near miss are you, spouse of the murderous day, cousin of the rubble, citizen of the melted mirror? They are, simultaneously, short, strange, and beautifully image-driven poems:

And that tire tread along the sand Each freshly-turned page invites you to revel in all the possibilities of Morrill's world: "a revolution's flag become a bedspread", "the clarity of an icicle, the white vein....spinning down its core", and even "destiny arranged by separate towels: for the hands, face, genitals." Surreal scenes melt into aphorisms before plunging the reader into one of many lives of the poet.

"Lives of the Poet" is, in fact, a single poem that comprises the entire middle portion of the book, and is divided into 25 sections with such subtitles as "the grand life," "the vigorous life," and "the devious life." As the broad use of the adjectives indicates, this poem is perhaps the weakest part of the book. Morrill's balanced grasp between image and adage slackens; the images lose their crispness, the precepts strike with less certainty, and even the speaker seems to acknowledge this: "It's elusive work, this defining." But Morrill wrestles his imagery back into its fine boundaries for the third and final section of the book. He concludes the collection with grand-slammers like "Twenty-Nine," in which "anything is possible but not everything," and "You, There, Listening," which asks the reader to remember that "poems are as impolite / as they are perceptive, as beside the point / as the actual." He grounds the poems in strong, visual experiences: August noon casting down its powdery halo, Here Morrill uses language with absolute precision, as if challenging us to conjure a scenario that is impossible to relate in words.

Ultimately, Awaiting Your Impossibilities is a highly satisfying read that will leave you dazzled and breathless, stumbling into the light as one who has crossed entire deserts while dreaming of dry wells and oases. "A poem's wilderness can make you mad that way." Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and received her MFA from FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

Brie Season by Jen Karetnick

(White Violet Press, Paperback, 95 pp., $17.00) Reviewed by Bonnie Losak |

Brie Season

Reviewed by Bonnie Losak I am not an adventurous eater. Unlike Jen Karetnick, author of Brie Season, I will not try anything once. Instead, my taste is guided by texture, by color, by smell, and too often, by familiarity. So I opened Karetnick’s new collection of poems unsure of whether food-focused poetry would be at all to my liking. But it was. Not only because Karetnick fills this collection as much with sensory experience as with culinary trends and woes, but because Karetnick is so skilled at noticing and celebrating the world around her and serving it up in delectable, lyrical morsels. Thus, in the second poem in this collection, “A Note to GK Chesterton,” Karetnick pauses to consider the unreliability of cheese as muse when there are great white herons that, amuse toddlers by stalking and,

the children we never One of my favorite poems in Brie Season is, “At the Holocaust Memorial,” perhaps because this memorial was an obsession of my younger daughter when she was four or five. “Tell me the story of the hand,” my daughter would say each time we passed the huge sculpture of an arm stretching upward, reaching, grasping. I told her as much as I thought her pre-school mind could understand. “There was a bad man,” I’d begin, and she’d listen, patient, as though she were following the intricacies, the horror I’d not quite described.

The next time we’d pass the sculpture, though, usually the very next day as it was on our route from home to almost anywhere, she’d ask about the hand again, never quite satisfied with the telling from the day before. I wish I’d had Karetnick’s words to help my daughter understand the suffering the memorial decries. The speaker in Karetnick’s compelling poem recounts her “first time touching the iron” of the sculpture: Nearly one hundred degrees under the sun, Like “At the Holocaust Memorial,” “Wake” is a poem that has both an international reach and a distinctly South Florida flavor. “Wake” is divided into three parts, the first of which is titled, “The Third Time Castro Died.” Here, Karetnick deftly describes the party preparations that follow yet another rumor of Castro’s demise:

Before the doubled police “First Drowning of the Season,” is also notable for its distinct South Florida feel. In this poem, Karetnick captures the manner in which a devastating event can become sadly ordinary:

The restaurant’s summer staff In Brie Season, Karetnick has managed to braid together her love of food and dining with the distinctive features of the South Florida culture to create a collection of poems that are intimate, intense, and wholly satisfying.

Bonnie Losak is an attorney practicing in Miami, Florida, and a MFA candidate at FIU. She lives and writes in Miami Beach. |

|

Suicide by Jaguar by Dave Landsberger, with translations by J.V. Portela

(Jai-Alai Books, Paperback, 116 pp. $16.95) Reviewed by Ariel Francisco |

Suicide by Jaguar

Reviewed by Ariel Francisco Reading Dave Landsberger’s debut collection Suicide by Jaguar is, as the title suggests, like voluntarily being devoured by something beautiful and powerful under bizarre circumstances. Published by Jai-Alai Books in a unique bilingual edition, it forgoes the traditional parallel format and instead allows the book to be read in English when held one way, and in Spanish when flipped in reverse, creating space for an undistracted reading that doesn’t prioritize one language over the other. In the opening lines of the first poem “Is It the Shoes?” Landsberger warns the reader that traditions and conventions are being thrown out the window from the get-go when he says, “Quiet tonight. Autumn evening’s onset/ and the cicadas are dead,” killing off one of poetry’s most beloved cliches, and preparing us for the unexpected. From here, the poet moves freely from humorous odes to actor Brendan Fraser and basketball player Blake Griffin, to poems like “South Beach Haiku 2,” which explores and pokes fun at the urban Miami landscape: Pekinese in purse yawning— This theme continues in “Miami Hates You” where he asks, “Why love something continually destroyed?” in reference to his love for the city in its seeming indifference to its inhabitants, and then honing in on the absurdity of it, stating: “A chimpanzee falls in love with a pigeon.” In “History Fair," he further emphasizes this complicated relationship when he quotes someone as saying:

The secret to loving Miami is to never say Landsberger uses the absurdities of Miami scenery as a stand-in for the strangeness of the fast-paced world we live in, our place in it, and how we attempt to orient ourselves. “Earth is Where I Keep My Stuff” illustrates this well, reconciling the macro and the micro with an almost attention-deficient air:

The fact that 54% of humans can’t swim gives me hope. J.V. Portela’s translations carry the poignant humor, sharp images, and leaping metaphors into Spanish. Landsberger’s lines:

Solstice in the feedbag, lunar tide in the horseshoe, keep their sincerity and intimacy as they become:

Solsticio en el morral, marea lunar en la herradura, Including Spanish translations with poems that have a Miami connection shows Jai-Alai Books’s commitment to representing Miami as a meeting place of languages, a crossroads of cultures.

Suicide by Jaguar is both hilarious and insightful without sacrificing one for the other, from cover to cover, no matter which way you read it. It makes us question not only what is happening around us, but what our surroundings actually are and what we’re doing there (or here). The book's last poem, “Morning Haiku,” encompasses this well. Just as the book opens with a question (“Is It the Shows?”), it ends on one: Heron splashed down by the waves: Ariel Francisco is a poet living and writing in Miami, Florida. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Jai-Alai Magazine, Sliver of Stone, Tupelo Quarterly, Washington Square, and elsewhere.

|

|

Prayer of Confession by Jen Karetnick

(Finishing Line Press, Paper, 29 pages, $12.99) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

Prayer of Confession

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta I never know what to expect from a chapbook. With so few pages compared to a full-length poetry collection, there is even more pressure for each poem to shine on its own while knitting the whole book together with each turned page. Jen Karetnick rises to this challenge with her new chapbook, Prayer of Confession.

Traditionally, the first poem in a collection is the most carefully chosen to establish what readers can expect from the rest of the poems. Karetnick's "Millipedes in the Wet Season" is no exception, although her witty, formal style is so nuanced that it is easy to miss. The couplets are lyrically driven, and brimming with the kind of striking imagery present in each succeeding poem: These dark columns Aside from its tight, clean lines, "Millipedes in the Wet Season" creates the expectation of a meditative, lyric chapbook. But Karetnick pushes traditional "meditative-lyric" poetry to its wits' end. Literally.

"Women on the Verge Discuss Viagra" follows closely behind the opening poem, introducing Karetnic's more playful voice. She manages to braid together rich imagery and humorous commentary as her speaker laments the misuse and unexplored possibilities of the "stamina boost": "How 'bout a pill to make them remember / to take out the garbage or mow the lawn? / One to defoliate the nose hairs grown. / Or better: to spark conversational vigor." It is also in this poem that Karetnick begins to introduce her formidable skill with formal traditions of rhythm and rhyme. A handful of these lines rhyme intermittently, as if by accident. However, as readers step deeper into her world, we realize that she is simply acclimating us to this sometimes-strange musicality. As I mentioned, a chapbook pressures each poem to become a gem. While each one in Prayer of Confession is beautifully crafted, Karetnick truly shines when constrained by traditional forms. Her range is impressive, spanning from basic rhyming couplets to villanelles and pantoums to deconstructed sonnets and true-rhyme nonce forms. Poems that rely on a formal structure of repeated lines work in concert with their imagery and occasions in such examples as "In Suspension," Arrival: A Love Villanelle for Haiti" and "The Truth about Ghost Orbs." Karetnick's poems traverse unexpected scopes of Florida, from the backyard subtropic underbrush and palms to spook-hunting field trips in Tampa. Each turned page reveals to the reader a new facet of both the poem's speaker and Karetnick's mastery of craft. Her humorous yet serious observations tap into what it means to be complexly and perplexingly human. Prayer of Confession challenges traditions of musicality and form, and of thought and contemplation. Turning each page is like turning a well-cut diamond that refracts the many angles of light. Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and received her MFA from FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

The Road to Emmaus by Spencer Reece

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Hardcover, 144 pp., $24) Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello |

The Road to Emmaus

Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello They were on their way to that town, Emmaus, In The Road to Emmaus, Spencer Reece explores the restlessness, the “little peace” that results from his estrangement from God, from others, and from himself. He sees it as the same alienation felt by the disciples after Christ’s death. They did not know where to go, or perhaps who they were without him. They argued, out of love, out of sorrow, and out of frustration. They were in pain. For the author, this pain ultimately comes from humanity’s separation from God. Yet, Reece explores how he sees that the hurt of that ultimate division manifesting itself in every wound of our lives whether we are believers or not. This is a book of ample tenderness, a tenderness that works to cure the divisions that wound.

Sister Ann’s face was open, fragile-- There is the sense that the author has worked hard to remove the veils covering his life. He speaks frankly and with ease. He appears to have acquired a patience from doing the hard work of self-reflection. He has arrived at the belief that his condition is one of brokenness, of frailty, and so he is able to face the world with compassion and insight. His poetics emerge from that humility. In “Margaret” he writes:

As you leave Margaret behind and turn the page, Reece’s work is unobtrusive. Even when he writes in abrupt homilies, such as, “It is correct to love even at the wrong time”, they seem suggestive, Socratic, the smooth wisdom of experience. The authority of the lines comes not from his forcefulness or self-righteousness, but from the momentum of what has been lived through and learned through the body, the mind, and the soul.

Reece is at his best when he shows how love is grafted into the darkest points of life: depression, anxiety, fear, and doubt. His poems attempt to act as liaison between a fractured humanity and the active love of a God who is ever-present, even though we may not see him. They are portraits of people, including himself, struggling to survive in the face of a relentless world. Reece, writing of his experience in Alcoholics Anonymous, says, I have often thought we were like first-century Christians-- His message is that every person is broken, and to a large extent is alone in experiencing life, but that the seed of love exists and reveals itself best in relationship with others. In shared experiences love manifests and grows, Reece maintains, even if we are stuck within the solitude of deep vanity. To him, it is relationship, both to others and to God, which can save, although the danger is that understanding the love that is present in a moment will happen only after that moment has passed, just as the disciples learned, nearly after the fact, that the man beside them was Christ. Their bickering blinded them. Their vanity had taken them out of relationship to each other and to God. And, for Reece, the only way to enter back into relationship is through patience and praise, as he does in the poem “Prodigal Son,”

In Miami, this May afternoon, I look up, And in the beginning of the second stanza,

The sun shines on the people The Road to Emmaus looks deeply into how the moments of grace in our lives can go unrecognized until after they’ve been lived, and sees hope in the possibility that struggling through those moments and seeing what has been missed is necessary in order to know it when the chance comes again. In these poems, Reece becomes the witness preparing the reader for the suddenness and subtlety of love. He writes as a disciple holding a light to the experiences of his life, making this book a gesture of compassion and generosity, a man returning and turning to what makes him feel most human.

Mother and father, Guillermo Cancio-Bello was born in Miami, Florida. He recently graduated from the MFA Program in Creative Writing at FIU. |

|

Lucky Bones by Peter Meinke

(University of Pittsburgh Press, Paper, 96 pages, $15.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

Lucky Bones

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta When I first picked up Peter Meinke's latest book, Lucky Bones, I was surprised to find that the first poem was a concrete poem in the shape of, as its title indicates, "Old Houses." After such a visually-striking start, I was unsure what to expect upon turning the page. What I didn't expect was an entire collection of poems that rhymed. Contemporary poetry seems to shy away from traditional forms such as iambic pentameter and both slant and true rhymes. No longer does a sonnet require the expected fourteen lines and ababcdcdefefgg end-rhymes with a well-placed turn. Now, an artfully written sonnet doesn't even need to be about love. Yet Meinke's poems are, in fact, all about love, in one form or another, and they hark back to the old-school rhyme schemes, and even the caesura as a punctuation device. Meinke writes in the opening poem, "Old houses / are best they have secrets [...] stories spread through / the rooms like the hint of camellias." Lucky Bones is, in a sense, like walking through the mind of a poet who has lived and loved immensely. This is a collection of nostalgic poems fondly recollecting "the walls dark with blood and age the dry taps laced with rust," and the memory of a Floridian Jesus Christ Lizard that "runs across water its eyes / seeing everything at once // and not with adoration." Nostalgia always comes with not only a joy for what was lived, but also a hint of wistfulness for what is now lost. But such a position of nostalgia also gives way to moments of wisdom for those just now beginning to live. You who inherit the earth after we drown But sometimes, there is also an element of playfulness that can't help but manifest itself, given the almost sing-song meter of the lines:

A martini's not strong enough Meinke continues to elevate these poems beyond nostalgia into a beautiful series of love poems for his wife, the artist Jeanne Clark Meinke. His poem, "The Activist," is dedicated "for Jeanne." At one point, he sweetly calls her "my mimosa / my warbler." And when she walks into the room, Meinke writes, "global warming's closer."

By juxtaposing the speaker's voice of reason and wit with such tender moments, Meinke somehow finds the delicate balance between the formal and emotional landscapes of each poem to keep Lucky Bones from spiraling into sappy sentimentalism. The poems in this collection offer a fresh and deceptively complex perspective on formal traditions. Nothing less is to be expected of Peter Meinke, the first Poet Laureate of St. Petersburg, Florida and emeritus professor of creative writing at Eckerd College. Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and received her MFA from FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

The Lame God by M.B. McLatchey

(Utah State University Press, Paper, 80 pages, $16.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

The Lame God

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta Because the adage is true that there are too many books and so little time, I've learned to devour poetry quickly. When I picked up M. B. McLatchey's debut collection of poetry, The Lame God, I expected to breeze through it as easily as any other book. But The Lame God is not like any other book. In fact, it is exactly the sort of book you can only read by pondering slowly. It is also a book that calls readers to action, even before the first poem begins. In the preface, McLatchey writes that roughly 2,000 children "are reported missing daily to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children." An opening epigraph next reads, "Acting quickly is critical. Seventy-four percent of abducted children who are ultimately murdered are dead within three hours of the abduction." In the first section, each poem resonates with the frustration of waiting helplessly for a child to return. The narrator in "1-800-THE-LOST" says, "I want her to discuss you in the present tense. // I want the gods to stop pretending love calls the departed home." Each subsequent section delves deeper into the anguish of loss. First, McLatchey shows the frustration which evolves into real and righteous anger, demanding that the guilty "choke up my child like the Olympians— / a girl, unbruised by her journey down their // throats." Then comes the lashing-out and self-blame. "Apology" is a list poem of regrets that will break your heart: For—trusting your safe return-- Finally, comes the acceptance—not of absence, or of seeking justice, or even of grief itself. No, these poems finally settle into the acceptance of waiting for news of any kind—good or bad—because either way, these parents will be there when their children come home. "Do not worry, daughter. We are not leaving our watch / or showing our cards—just changing the guard."

McLatchey is the poet standing at the gate, holding a torch to keep hope aflame even as the darkness descends. A graduate of Harvard University, Brown University, and Goddard College, McLatchey currently teaches writing and humanities at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona, Florida. Well-versed in Classical mythology, she knows how to grit her teeth and tell the traumatic story in a way that will make people listen. She is the rare poet who looks fearlessly and closely at the terrible actions of which humans are capable, and who tenderly yet artfully tells the true stories of Adam Walsh, Amber Hagerman, Levi Frady, Maile Gilbert, Morgan Chauntel Nick, and Molly Bish, whose mother "encouraged [McLatchey] to 'keep talking about this; keep writing.'" When Edward Field chose The Lame God for the 2013 May Swenson Poetry Award, he wrote, "it takes courage to read this book...In exploring such a grief through the language of poetry, McLatchey makes things happen—she gives a voice to those too grief-stricken to speak, and she refuses to allow us to suffer in silence." This book is not for the faint-hearted, or for the "breezy reader." This book is for those 2,000 children daily reported missing, for their families, and for those moments when poetry alone can break through the grief. "But it is especially for the child who has not yet pried open a bolted door, borrowed a neighbor's phone, and announced to a 911 operator, 'I've been kidnapped and I've been missing...and I'm here.'" Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

Systems of Vanishing by Michael Hettich

(University of Tampa Press, Paper, 106 pages, $14) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

Systems of Vanishing

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta "Think of us humans with somewhere / to go, moving quickly." It seems that we are always rushing from one thing to the next, unable to fully appreciate each moment, until pieces of our lives drift away, unnoticed, and eventually vanish altogether. This fading-away is the central theme of Michael Hettich's twelfth poetry collection, which won the Tampa Review Prize for Poetry. The first lines in Systems of Vanishing begin: "And so I understand, at least for a moment, / how something and nothing can sometimes be reversed." Opening the book with the word "And" implies that the speaker has spent time meditating on "something" versus "nothing." Already there is an omission of the struggle that brought the speaker to that new understanding. In every subsequent poem, the speaker notices something that has been lost—the loose threads from clothing, a 2,500 year old Buddhist monastery, even summer trees full of "black birds trimmed with rust." Hettich invites readers to enter his version of South Florida, full of star fruit, turtles, and an ocean that "takes me where it will." He is a true lyric poet, relying on fluid language and beautiful metaphor to unravel his narrator's "stories like old rope until they won't hold / and your boat is set free to drift." In the collection's title poem, Hettich tells the story of a boy picking apples with his mother. At one point, she steps off the ladder "into the tree and seemed / really to disappear, / which scared me." By illuminating this tiny moment, Hettich asks readers to explore our own relationships with the precious things in our lives, both before and after they have vanished. He reminds us, in "The Ache," to be present in each moment, and not to rush through the world because, "We don't mean to come to the end of our lives / before they come to our end, but we do." Perhaps this comes as a hard-earned revelation for Hettich's narrator, as demonstrated in the long poem, "And We Were Nearly Children." The poem opens with the speaker "reading in my garden on a Sunday afternoon" when he realizes that he rarely thinks of the newborn daughter he and his wife lost thirty years ago. "We'd started // a gallery and tiny small press bookstore / and thought we might even make a go of it that way, // so your mother could give you her days." This poem follows the family as they rejoice through the pregnancy, only to lose their daughter amid unexpected labor and a midwife's ill-handled panic. Through the raw heartbreak of losing a beloved child, the speaker is full of yearning when he says, "Audrey, let me tell you now // from the distance of all these years," how much they still love her even as she fades from their thoughts. This gives a profound new meaning to the art of vanishing. Systems of Vanishing is a beautiful and elegiac tribute to everything we lose, both precious and minute. This is perhaps Hettich's best collection yet. Be prepared to slow down for just a moment, step into a fading world, and practice your own system of vanishing. Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

Bachelor Pad by Stephen Kampa

(Waywiser Press, Paper, 104 pages, $17.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

Bachelor Pad

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta Whenever I tell people I am a poet, inevitably someone asks what kind of poetry I write. Specifically, they want to know, "Does it rhyme?" Usually I say no, contemporary poetry has moved away from the whole rhyming business. These days, formal poetry is most often used as an exercise in dexterity of language and meter, much like practicing music scales. Imagine my surprise upon reading Stephen Kampa's second poetry collection, Bachelor Pad, in which nearly every poem follows a different, complex form of rhyme and meter. This complexity is what captured my attention first. Here was a poet who rhymed—and rhymed well. I found myself caught up in the rhythm and rhyme driving the energy of such poems as "One Table Over": How distant Christ's divine Tetelestai At first, I found the musicality of the rhymes stretched across each verse to be charming, almost whimsical, creating a light-hearted atmosphere—that is, until I remembered that the poem was about a couple whose marriage was publicly falling apart. This was the true power of Kampa's poems.

In an interview with the Academy of American Poets titled "The Art of Finding," the poet Linda Gregg spoke of how people tend to admire poems "chiefly for their craftsmanship and musicality [...] along with the patterning and rhymes." But in doing so, the real value of the poem is missed. Gregg goes on to say that what matters "even more than the shapeliness and the dance of language is what the poem discovers deeper down than gracefulness and pleasures in figures of speech." What I found in the depths of Kampa's poems was more than carefully crafted language or cleverly integrated meter. Instead, I found myself connecting with the expression of insatiable broken-heartedness. I admit I was skeptical at first about this book so boldly titled, Bachelor Pad. I braced myself, certain to find poems based on a slew of lusty exploits that would make me, a female reader, cringe. But for Kampa, a poet who won the 2010 Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, the 2011 Gold Medal in Poetry from the Florida Book Awards, the Theodore Roethke Prize, and the River Styx International Poetry Contest, I knew there had to be something more. Indeed, there was. I found no sexy poems, no seductions or conquests, not even a heaving bosom. Instead, I discovered a mournful speaker unlucky in love. The second poem in the book, "Plenty to Him," starts out: "Already there were signs / That they would not have sex or something more—" followed by poems in which the speaker recognizes what he's lost upon seeing an ex-lover at a laundromat, or else comes to terms with his endlessly poor luck "After you've met / The wrong girl yet again." Kampa's narrators are not all about lament and self-pity. Many poems have bright moments of revelation in which the speaker tries to make sense of his continuing single status: "That being full depends on who is filling." Or, that "crumb by crumb we find / Pain is the bread we eat," giving him hope to keep looking. Kampa uses the formal aspect of his poetry to do what Linda Gregg calls combining the tools of poetry "with the meaning to make us experience what we understand." Bachelor Pad is for anyone who has ever lost a lover—or more than one—and who seems fated to be alone. For anyone who has ever masked heartache with a shrug and a smile, who doesn't give up hope, these are poems full of solace. This is a book for the bachelors—and bachelorettes—past and present. Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

On the Street of Divine Love by Barbara Hamby

(University of Pittsburgh Press, Paper, 144 pages, $16.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

On the Street of Divine Love

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta In the winter of 2011, I was wrapping up my first semester as an MFA student, and although I love South Florida's 80-degrees-in-December weather, I was missing the northeastern snow of home. It was finals week, and I had had no time for pleasure reading. But I happened to pick up the November/December issue of The American Poetry Review and flipped it over. Taking up the whole back page was Barbara Hamby's "Ode to Forgetting the Year." This wasn't any melancholic Keatsian ode, or an ode in the tradition of mudane-objects-turned-extraordinary Neruda. Oh no, this was a jubilant ode that was downright funny. Forget the year, the parties where you drank too much, Throughout that winter break, I couldn't get that poem out of my mind. I had to know more about Barbara Hamby and her poetry. Her debut collection, Delirium, won the 1994 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry, the Norma Farber First Book Award, and the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. The Alphabet of Desire (1998) won the New York University Poetry Prize, and Babel (2004) won the Donald Hall Prize in Poetry. Her first foray into fiction, Lester Higata's 20th Century (2010), received the Iowa Short Fiction Award the same year she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She and her husband David Kirby, also a poet, co-edited the humor poetry anthology Seriously Funny, and she is currently a Distinguished University Scholar teaching creative writing at Florida State University.

Since reading that first ode, I've slowly read through her other books, marveling at her jazzy, rollicking syntax and playful sensibility, demonstrated in such poems as "Betrothal in B Minor": "All women bewail the betrothal of any woman, / beamy-eyed, bedazzled, throwing a fourth finger // about like a marionette." When On the Streets of Divine Love came into my hands, I was eager to see how the new poems worked alongside selections from previous collections. One of the perks of reading a selected-works collection is being able to see how an author has developed or deviated from skills and themes in her earlier poems. I found that the work included from Delirium was just as striking as her newest poems. From the first, she demonstrates an insatiable hunger to know the English language as it exists today in al its pliability, "for ours is a language of materialism first, // a language in which ideally everything you need is obtainable." If anything, Hamby's love of language and cultural history have expanded with each collection from such poems as "Hatred" from her second book, to "Ode to American English" in her third, and "I'm Making Walt Whitman Soup" in her most recent work. Hamby isn't just having fun with language; she's throwing the whole of history and culture into the mix. Mockingbirds and Mr. Rogers sit next to Dosso Dossi and the devil; barbecue and Bozo the Clown somehow fit with short skirts and Donatello's David. Humor and death walk hand-in-hand through each poem. If you can only own one Barbara Hamby book, this should be the one to grace your bookshelf. She translates the years into "the language of bees...into onyx, into Abyssinian / into pale blue Visigoth vernacular," forgetting nothing, offering us an ecstatic exploration of the oddities that make up art history, American pop culture, even poetry itself. On the Street of Divine Love is a delightful linguistic smorgasbord in praise of this world of fascinating oddities in which she exists as both poet and person. "[A]nd in the white nights of summer / we became poetry, every breath an iamb." Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

A Wilderness of Monkeys by David Kirby

(Hanging Loose Press, Paper, 104 pages, $18) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

A Wilderness of Monkeys

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta I've never been able to answer the question: What six people, living or dead, would you invite to dinner? Too many choices, too many conversations I would like to have. Einstein? Da Vinci? Whitman? After having the pleasure of reading David Kirby's tenth collection, A Wilderness of Monkeys, I realized that the dinner question isn't so much a matter of favorites as it is one of strategy, much like using the last of the three proverbial wishes to wish for a thousand more wishes. If I were to invite David Kirby to be one of those six dinner guests, I would, in fact, get a menagerie of historical figures—at least, I would get Kirby's version of them—from John Montagu, Fourth Earl of Sandwich, to Thomas Jefferson , to Buzz Aldrin. If Kirby's poems are any indication, he would be the life of the party, regaling, among others, Jane Austen and Nikola Tesla with anecdotes of doing yoga in the airport, or sending fan mail to Michael Byers, all with a classy glass of wine in his hand. I first discovered David Kirby, the Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of English at Florida State University, at the Sanibel Island Writers Conference in 2011. During a poetry workshop, as I was scribbling away Kirby's methods of sparking a poem, of submitting work to magazines, he said he had recently overheard two girls in front of a building on his campus. One girl said to the other, "I'm kind of a whore, but she's, like, way a whore." That phrase has stuck with me for years. What a surprise to see it as the title of a poem in A Wilderness of Monkeys. I was surprised, too, to find in the poem, alongside those girls, The Grateful Dead, Mark Twain, Hoosiers, ketchup, and mathematicians. Kirby—or, "the Kirb," as he refers to himself when he becomes one of his poems' own "historical figures"—is an impossible mathematician in his own right, adding characters, facts, and events by the handful into a single poem, and somehow making it equal success. This proficiency has led him to be nominated for the National Book Award and garnered a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Brittingham Prize in Poetry, inclusion in Best American Poetry, and the Florida Book Award. Now, he's done it again with his tenth collection of poetry, A Wilderness of Monkeys. The book is divided into four, self-contained mini-collections. The first section describes desire: to know, to love, to be free—big desires. The second feels largely autobiographical, and encompasses such strange crowds as "Legion, For We Are Many," and "Sexy Republicans." In the third section, Kirby unspools little life moments, and remakes myths and daydreams in poems such as, "Jesus' Dog," which is a wonderful retelling of the Persephone myth, and "Motherfocker, Prince of Wails," an exploration of Shakespeare's Hamlet. In the fourth section, Kirby addresses poetry itself, language, and "The Things We Can't Have." He ends the book with a poem of direct address: "To a Poet Living Two Billion Years From Now." In it, he says, "Look, I've got Whitman by one hand, future poet, // and I'm reaching out to you with the other...But it's not the poem / you need. That poem hasn't been written yet, / and you're going to be the one who writes it." Back at that presupposed dinner party, Kirby moves around the room, until he reaches an aspiring young poet, two billion years behind him. "You're going to write the poem that gets us out of this mess," he says to this poet. He raises his glass of wine, his poems still ringing in our ears, and he says with a wink, "You're going to write a poem that blinds us." Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

The War on Pants by Kristine Snodgrass

(Jackleg Press, Paperback, 60 pages, $13) Reviewed by Leslie Taylor |

The War on Pants

Reviewed by Leslie Taylor Kristine Snodgrass’ first full-length book of poems, The War on Pants, has a thesis statement of sorts, a quote from a news story about a robot designer, as its epigraph: “‘What is a human?’ he asks. ‘Please define and we will make a copy.’” The poet then gives us a series of poems and soundscapes exploring themes and topics ranging from gender identification to memes, in what reads like a collection of poems from a dystopian future. The titles and some of the language concern robots: “Robot, Girl,” “Gender and Robots,” “Robot Almanac,” Robot Rage,” and “Robots and Church.” There is a sense of pessimism about the future of technology and gender that permeates the poems. “We are generous with our vaginas, like philanthropists” states the single line of “Robot Whores.” Snodgrass is aggressive yet mysterious in her commentary and imagery. Even for a poetry book, there is a lot of white space, a lot of room for the audience to wonder where the poet is taking them, a lot of space for meanings to fall behind. The most interesting moments in the book are fueled by the poet’s playfulness. “Then Orpheus, List” starts as a repetitive syntax poem, then transforms into an untraditional ballad, and concludes with the repetitions again. It is a beautiful mixture of styles and language and sound. Metamorphosis. Die! And gay sang and see night as angst. That’s the off sang. See night as angst. That’s the off sang. Sing and die, the off sang. Sing and die. The off sang. Sing gay and die. The off sang. Wanna ampersand? & die. & die. & die. The off sang. Order fang and bereft. & die sang. List, list, list. The poem functions both in experimenting with words and sonic textures, but also as a homophonic translation of Rilke’s “Sonnets to Orpheus” (1-5). It is this mixture of old and new that captures Snodgrass at her best.

In the poem, “Mend The Pants,” the phrase “Mend the child’s pants” transforms into “Mind the child” to “Mind the verb” with a dozen other variations. The poem is an example of concrete poetry; it is shaped by its line breaks as a pair of pants. Thread the needle and the pants will mend. Thread the needle/ and the pants will mind. Mind the thread. Mind the needle. Mind the child. Mind the pants/ and the threads. Mind the child’s pants. Mind the child’s thread. The needle in/ pants.The needle in pants and thread. The needle in the pants and thread is minding the/ child. Mind the child and the/ verb. Mind the verb. The/ verb is IS. Snodgrass’s primary technique here is repeating a phrase with slight alterations every few repetitions. The meaning transforms in each repetition, beginning as an everyday phrase, but warping into a comment on gender and child rearing. Reminiscent of Gertrude Stein, but more accessible, Snodgrass allows mundane phrasing to warp and gain new, subversive meanings.

But repetition can become tiring to the eyes, and there were times when I felt a shorter poem tightened to the more meaningful lines could be stronger. Her poem “Robot Resentment” is one example of a poem which over utilizes repetition without enough variation or payoff. The repetition of a line like “No, you’re wrong. No you’re wrong. Say it again. No you’re wrong. Say it again, you’re wrong.” can be hard to follow or to find the powerful moments like those in “Mend the Pants” or “Then, Orpheus List.” In this instance, the technique seems to have more theoretical interest than actual enjoyment. The largest concern I have is with the one-line poems. One-line poetry is a delicate art of subtlety and inference. The poem “Robot Social Networking” reads, simply, “You are a moron.” The intended effect seems to be along the lines of criticizing the audience and society, but I saw it as a cheap shot. Societal critique can come off as late night comedy. The poem “Sexting” contains the line, “You are defining my sexuality, Anthony Weiner.” I am a fan of Oulipo and experimental forms, so I came away from the book desiring more: more commentary on gender, more playfulness with form, more of the concrete poems like “Mend The Pants.” With this first book, Snodgrass has created an interesting beginning. I hope Snodgrass will build on these themes in her future works to reach deeper and continue exploring the frontiers of language, technology, and gender. Leslie Taylor is a graduate student at Florida International University's Master's in Fine Arts program in Creative Writing. He enjoys Oulipo literature, hobby board games, and talking during movies. |

|

Landscaping for Wildlife by Jen Karetnick

(Big Wonderful Press, Paperback, 40 pages, $14) Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello |

Landscaping for Wildlife

Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello Florida is sawgrass and swamp, mango y papaya, arroz con pollo, black beans and rice, oranges, and star-fruit dangling above the ionized chain-linked fence separating two pink houses. Florida crawls, and creeps, and looms like an alligator’s dark back with its great jaw hidden beneath the water’s surface. Jen Karetnick’s Landscaping for Wildlife puts that wildness into form. The book begins with the poem “Adult Congregate Living Facility”: Peacocks nest on the roof of Nightingale Manor. These congregants are not only the despairing elderly imprisoned by age and failing bodies, they are representative of the human condition in which we are all imprisoned. Karetnick includes herself among the suffering.

and I shout, too, to any god there is for a measure In this, the book's first encounter with wildness, the peacocks, symbols of pride and beauty, are themselves "housebroken," while we see the wildness of human rage against the boundaries of life which seem to close in on us, and our anger with ourselves for the ways we engage the anxiety of those encroaching borders. This poem presents the contradiction of wanting total freedom, and reaching to bring form to a life. And as a reader I'm left wondering to which god the author shouts.

Karetnick plays with form, to some degree, in every poem. “Echolalia” consists of two sonnets—actually, one sonnet that is a mirror of itself so that the last line of the first poem becomes the first line of the second poem, the next to the last becomes the second line, and so on. It is, as the title suggests, a play with repetition. The poem speaks of her colicky baby, and the reader can imagine the merciless repetition of that sharp cry and how it led the author to the poem’s form. In fact, it is the reiteration of lines and rhyme that emphasizes the infant’s barbaric squeal. Once again, it is form that gives wildness its voice. In her title poem “Landscaping for Wildlife” Karetnick returns to the idea of confinement versus liberation. First, fire the gardener, then disable the gas-powered mower. The first line indicates that ‘landscaping’ is not a noun as in ‘landscape’ or ‘landscapes,’ but instead it is a gerund, which indicates activity, making the title a verb phrase, an action. She is asking the reader to disengage, to landscape so that what is wild can thrive. We are not to pare-back or take-away. Throw the scissors down. Open yourself to the crabgrass creeping over flagstone Landscaping is a cease-fire. “Remove everything/non-native, including yourself.” This is not repairing land or restructuring it to include wildlife as well as humans, this is a complete removal of human constructions. This is the reign of wildness. This is the impulse from the first poem to declare that freedom is formless. This is the scream, the cry of the wilderness in us. However, Karetnick turns at the end of her poem.

Should you desire the tin-roof company of Caribbean parrots, Karetnick implies that, without form, what is left is indistinguishable from a heap of compost. Form brings beauty. In trying to live without form you must be prepared for the consequences. Yet, even in the absence of a human structure, wildness is governed by some loose geometry, though it may not be a figure we would choose to engage, or enjoy. The fact is human involvement brings form. It is in the act of engaging wildness that we begin to transform it. This is what Karetnick has done in her latest collection, constructed poems that sing her wild voice.

Guillermo Cancio-Bello was born in Miami, Florida. He recently graduated from the MFA Program in Creative Writing at FIU. |

|

The Biscuit Joint by David Kirby

(Louisiana State University Press, Paperback, 80 pages, $16.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta |

The Biscuit Joint

Reviewed by Marci Calabretta David Kirby's most recent collection of poems, The Biscuit Joint, is its own manual to the author's poetic process. Kirby claimed his niche in the poetry world with such collections as The Ha-Ha (2003), The House on Boulevard Street, a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award, and Talking about Movies with Jesus, which won the 2011 L.E. Phillabaum Poetry Prize. Now, without losing his famous sprawling syntax and snowballing imagery, Kirby has achieved a voice of deeper maturity that comes with 89¢ "senior coffee." Kirby, the Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of English at Florida State University, boldly opens The Biscuit Joint with the poem, "Why I Don't Drink Before Poetry Readings," a two-page introductory piece that is just one sentence. The narrator admits to avoiding alcohol "[b]ecause it's as though even a single drop of alcohol / awakens some area of your brain in which a thought / will begin to take shape the way a mushroom appears / on your lawn after a heavy rainstorm." That single drop swells into a phrase that is "all but unholy, has turned into / something so horrible that you'll be lucky if anyone / who hears it ever speaks to you again." However, as both the imagery and imagination intensify, Kirby gracefully executes his signature move of harnessing the escalating energy of his lines into a sculpted finish, in this case, coaching the narrator to "take a deep breath and let half / of it out and look down at your pages and then up again / and open your mouth and say, / 'Thank you, thank you so much for that lovely introduction.'" That first poem sets the tone for the rest of the book. Readers experiencing Kirby's poems for the first time might be surprised, perhaps even daunted by the complex and lengthy sentences, but those familiar with his meandering and introspective style will find a heightened sense of self-awareness woven through each poem. "If the poems work," Kirby reveals in the Notes page, "they work best when they move the way the mind does...I tend to start with a small thought, watch it snowball into something beyond itself, and, after a couple of minutes, do my best to bring everything together and make something that'll stand on its own." A compelling example of this is in "East of the Sun, West of the Moon," which moves rapidly yet fluidly from the narrator's mother's funeral to David Copperfield to the question, "what is a moly and why is it holy." Kirby spins the chaos of the mind's associative leaps into a tapestry of strength found only in living and tugging at the threads of sword-fighting and Sherlock Holmes, Turandot and train rides through Siberia. He also shares a private perspective on death and the gravitas attached to being "almost happy": "My father is the first of our parents to die, and when / he does, Barbara says, 'We only have to do this three / more times, right?'" Kirby's collection is aptly titled from The Complete Woodworker's Bible.The opening of The Biscuit Joint explains that a "biscuit joint" is defined there as a technique of joining two pieces of wood. "Done right, the joint is stronger than the wood itself." Every image and poem in Kirby's most recent collection is joined together and strengthened by the narrator's own delightful train of thought, the wild and scenic route upon which everything hinges. "And though poetry doesn't mean anything to most / of you, a lot of you are in those poems I wrote / earlier, and you're all in this one. Come on / in, Grandma! You can sit next to Federico García Lorca." Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her work has appeared in Rainy Day, The Albion Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the co-founder and managing editor for Print Oriented Bastards and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

|

Bearable Weight by Michael Cleary

(Word Tech, Paperback, 94 pages, $14) Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello |

Bearable Weight

Reviewed by Guillermo Cancio-Bello Weight of loss, of love, of regret, weight of sadness, of faith, of doubt, unbearable weight of existence and death; Michael Cleary’s poems each lug a piece of the load of living. He was raised in the Adirondack town of Glens Falls, New York, and now finds himself living in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Bearable Weight is his newest collection of poems. The book is broken into two sections, Flummoxed and Points in America. They speak to the two halves of his life: youth and adulthood, Glens Falls and Fort Lauderdale, faith and doubt, innocence and experience. They create a topographical map by which the reader can feel around and sense the emotional landscape, and the development of that landscape. The collection begins with the poem “Adam and Eve Make Love.” It opens with the lines, “Paradise gone/for good.” This idea of paradise lost, of the inability to regain not only innocence but also a seamless and unshaken faith is central to the work as a whole. The vanishing of paradise implies that it once existed, and should exist but doesn’t, and therefore we are left with an ache, a hunger. For Cleary it is desire that satisfies, at least briefly, our longing. It is this earth, this body, our hunger and the ability to answer and respond to it in thoughtful ways that makes us human. It is “making love/out of what’s lost,/a world/out of nothing/but one another.” All we have is what is left after paradise, and we must make the best of it. Throughout these poems there is a struggle between the spiritual and the corporeal, between the sacred and the profane. He defines the battle in his poem “Carnal” with the lines, “Each day/a see-saw/quarrel with/spiritual.” He goes on to say that the carnal is our only “consolation” for what we now lack after our fall from paradise. He ends with the lines, “The body’s/despair undone:/the bearable weight of/mortal.” He ends with death, death as the final reprieve from the struggle not only of living, but also of trying to define what living means. Yet this book is an attempt to add at least a word to that definition in some way, perhaps just a syllable. Cleary understands there is a power behind every word. Watching my deaf student listen, Language becomes a way to reach the meaning for which he longs. Language itself may even be a conduit to that meaning.

Cleary is at his best when he locates that spiritual struggle and the hunger for meaning in events from his past that have marked him significantly. He speaks with keen tenderness of his first marriage and divorce in his poem “First Wife.” I see now something dark was passing The idea of loss, or absence, becomes a physical object, a mirror. This loss existing as a physical space between two people is not only a retelling of the fall of Adam and Eve, but a lived experience in which the lovers are unable to see each other and move closer. Instead, each is trapped in vanity and self-pity at having lost each other, lost paradise, and for that act were unable to forgive themselves.

As the poems move forward in time the darkness of loss, although a presence, has become less of a threat as if the author in the writing of these poems has come to terms with his own nature and its place in a larger world. Among bright ocean swells The poems grow from the confusion of Flummoxed where Cleary is “desperate/with the night’s last song” nearly broken by the weight of living, to the acceptance of Points in America where “cuts and sores healed so rough/the hide never forgives its hard lessons.” These later poems written in Florida become not paradise regained, but rather a relinquishing to an unknowable power, an acceptance of the fall. What is left is this body in this life among the other living. For Cleary, Florida is a coast to stand on and look out at a horizon that can never be reached but only observed and felt as a distance, as wind, as wave after endless wave. Florida is the symbol for Cleary’s metaphysics: a body reaching into endless and unfathomable waters.

There are no angels here, Guillermo Cancio-Bello was born in Miami, Florida. He recently graduated from the MFA Program in Creative Writing at FIU. |

|

He Do the Gay Man in Different Voices by Stephen S. Mills

(Sibling Rivalry Press, Paperback, 100 pages, $14.95) Reviewed by Julie Marie Wade |

He Do the Gay Man in Different Voices