FBR Feature: José Martí

In Search of Florida's José Martí

By Dariel Suarez

By Dariel Suarez

|

Rediscovery

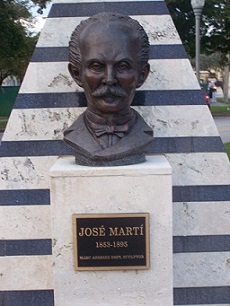

A few years ago, on the day my wife and I moved to Coral Gables, we decided to take a stroll around the neighborhood. Across from the Coral Gables Women's Club, on a triangular section of sidewalk and grass that divides two diverging streets, stood a well-kept monument of José Martí. The statue didn't look to me much like the photos I had seen of the man except for the recognizable receding hairline and thick mustache. What struck me most, however, was the fact that a statue of the national hero of Cuba, where I was born, had been placed here, as if on his own isolated piece of land, so far away from where I thought he belonged. Recently I learned that José Martí has a Florida literary landmark in Key West, and that he is considered a Florida writer. As someone who grew up the son of a decorated Cuban journalist, I felt both confused and embarrassed, as if I should have known this, as if this curious piece of information should not seem as perplexing to me as the monument near my home. Suddenly, I needed to know how Martí had become a Florida symbol. I decided to visit José Martí's literary landmark to find the connection. The Institute The San Carlos Institute stands at 516 Duval St., and is promoted as "a multi-purpose facility," serving as "a museum, library, art gallery, theater, and school." The building's façade has distinct structural features that even someone like me who knows little about architecture can recognize as Cuban: the large balcony, the multi-layered columns, the narrow, high wooden doors that resemble windows. If that weren't enough, Cuba's National Coat of Arms peeks out at the top, a clear symbol of the building's correlation to my home country. |

|

In the 1890s, members of the Cuban émigré community in Key West, most of whom had left their country due to Cuba's war of independence against the monarchy of Spain, referred to the San Carlos Institute as the "Cathedral of Cuban Patriotism," "The House of the Cuban Spirit," and "The Soul of Cuba." José Martí referred to it simply as "La Casa Cuba."

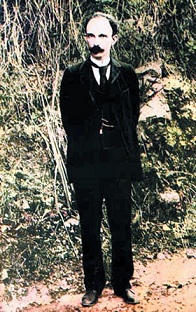

Walking its ample, freshly-painted rooms, I recognized there had to be a deep-rooted history between Martí and this place. Florida Arrival Born in Havana in 1853, José Martí spent most of his adult life in exile. He was deported from Cuba in the late 1870s for plotting against Spanish rule. During this time he travelled around Latin America before settling in New York, which became his home. There he made a name for himself by working diligently to unite the numerous Cuban émigré factions, including the ones in Florida, in order to support the revolutionary war against Spain. As a result, he came to be known as an active advocate for social justice, an unparalleled speaker and skillful writer, and the brilliant architect of an impending uprising on the island. |

|

He was formally invited to Key West after a successful trip to Tampa in early 1891. Some of the most influential figures of the Cuban exile had been thoroughly impressed by Martí's ability to convince the tobacco workers, in just three days, to donate large amounts of money for the revolutionary cause. In addition, over four thousand Tampa residents had gathered to see him off. Martí had established himself as the most prominent leader of the émigré communities.

By December 25th, 1891, when Martí reached Key West, copies of his Tampa speeches had been circulated. A flyer announcing his arrival had been distributed from door to door in the Cuban colonies that surrounded the tobacco factories. Throngs of people assembled by the pier at the end of Duval St., where he was received with joyous clamor, boisterous praise and, according to witness accounts, even tears. Martí refused to ride in the carriage that had been arranged for him. Instead he walked with the people all the way to Duval House, a distinguished hotel where a lavish banquet had been prepared in his honor. Despite being severely ill, he participated in the event and gave a short address. Then he went into seclusion for a week at the advice of a doctor. |

The Key West Speech

On January 3rd, 1892, a reenergized and focused José Martí stood on the balcony of the San Carlos Institute. He looked over an audience surpassing 5000 people and delivered a historic speech that not only invigorated Key West but secured his status as one of Florida's earliest celebrities. Newspaper reporters claimed that his capacity to enthrall, move, and persuade both the working masses and cultured leaders was like nothing the émigré community had ever witnessed.

Martí impeccably used historical, biblical and philosophical references. He spoke of social equality, prosperity and freedom with honesty and fervor. The crowd reacted to his emotive words by listening in absolute silence, waving Cuban and American flags, and applauding ardently during pauses. A correspondent of Key West's local newspaper El Porvenir described the scene as an Evangelist preaching to his devout followers.

On January 3rd, 1892, a reenergized and focused José Martí stood on the balcony of the San Carlos Institute. He looked over an audience surpassing 5000 people and delivered a historic speech that not only invigorated Key West but secured his status as one of Florida's earliest celebrities. Newspaper reporters claimed that his capacity to enthrall, move, and persuade both the working masses and cultured leaders was like nothing the émigré community had ever witnessed.

Martí impeccably used historical, biblical and philosophical references. He spoke of social equality, prosperity and freedom with honesty and fervor. The crowd reacted to his emotive words by listening in absolute silence, waving Cuban and American flags, and applauding ardently during pauses. A correspondent of Key West's local newspaper El Porvenir described the scene as an Evangelist preaching to his devout followers.

|

Martí and Florida

In the days following the San Carlos speech, Martí held important meetings in Key West for the Cuban cause. He was assigned delegate, since he refused to be officially called President, of the newly-formed Cuban Revolutionary Party. He felt the word "delegate" implied actual responsibilities as a representative of the people. As such, he intended to succeed in funding Cuba's liberation from Spain's colonial stranglehold. He finally departed Key West on January 6th, leaving behind another sizable crowd of emotional followers. Martí returned to Florida several times in a continuous campaign to keep the divided émigré communities organized. He exchanged letters with both friends and those who opposed his style of leadership, and drafted important documents for the party. He gave a few more speeches at the San Carlos Institute, some in English to North American audiences, in which he asked of them not to judge Cuba's apparent lack of effective action against Spain. Time and again thousands of people congregated to see him. Some of his political and social articles, published in local newspapers in Key West, influenced the curriculum in a number of Cuban-populated schools. He even visited some of them and spoke to the students. Curiously enough, Martí was known for proposing "the substitution of the literary for the scientific spirit." He believed that a nation, in order to flourish, needed more than just intellectuals. Death in Cuba Armed with sufficient funds, José Martí returned to Cuba in April of 1895 as part of an expedition intended to set the new revolution in motion. Alongside General Máximo Gómez, he united with Cuban rebels and began fighting Spanish troops. On May 19th, in the Battle of Dos Ríos, he was told to stay behind while Gómez led his men to confront Spanish soldiers. Martí, who had been criticized by military commanders for his reluctance to engage in combat, decided to disobey orders. As he rode his horse towards battle, he encountered a Spanish column. A rattled Martí took out his pistol, prompting one of the opposing soldiers to fire. |

The San Carlos Institute

Founded in 1871, the San Carlos Institute was intended to be a place where Cuban values could be preserved away from the island through teaching. The fairly small wooden structure on Anne St., at the time one of the very few bilingual and integrated schools in the United States, was eventually moved to a larger location on Fleming St. in 1884. Two years later the Institute burned down in a fire that demolished most of Key West. A new and improved building was erected on Duval St., in 1890, the site where today's literary landmark stands. The two story building contains exhibit rooms where numerous documents, photographs and artifacts offer a glimpse into Cuban History. The San Carlos also holds the "Life and Works of José Martí: 1853-1895," a collection of documents and photographs of the Cuban martyr, donated by Florida International University. The site is currently maintained through private donations and is managed by a board of volunteer directors. Learn more at the San Carlos Institute Website. |

Though the details and circumstances surrounding his death are still disputed, it is said he died facing the sun, as prophesied in one of his poems.

|

Legacy

As I surveyed the Cuban-themed displays in the San Carlos Institute, I saw myself back in my home country for a moment. I wondered if this was the feeling that captivated Martí each time he travelled down to Key West. Perhaps that's what his followers saw in him, this man they called "The Apostle," "The Evangelist," "The Master," and "The Martyr," a hopeful reminder of what had been left behind, a tangible symbol for a nation struggling to find its identity, a nation whose people, like me, found a second home in Florida. The Institute that Martí knew was destroyed by a hurricane in 1919. The one solemnly standing on Duval St. today was completed in 1924 and almost demolished due to its dilapidated condition in the mid-1980s. Thanks to efforts by the Florida Hispanic Commission, the building was restored, reopening its doors to the public in 1992. Had the Institute been leveled, José Martí might not have a literary landmark. He might not be officially considered a Florida writer. Nonetheless, this state remembered, revered, and ultimately adopted him. He is one of ours. His name and image are celebrated in monuments all over the state—from Key West to Miami, Tampa, Orlando and Gainesville. As for myself, I feel as though I understand his puzzling monument in Coral Gables a little better. I understand José Martí and Florida's history a little better Dariel Suarez was born in Havana, Cuba, where he lived until 1997. He resides in Miami with his wonderful wife and a large number of books. Dariel's fiction and poetry have appeared in several publications including Skive, elimae, Vain, and The Absent Willow Review, where he received an Editor's Choice Award. This feature, his first non-fiction publication, is dedicated to his father. |

More info on José Martí may be found here:

— J.A. Sierra's History of Cuba

— La Pagina de José Martí (in Spanish)

— J.A. Sierra's History of Cuba

— La Pagina de José Martí (in Spanish)