FBR Feature: Harriet Beecher Stowe

"The book of Nature here is never shut":

A Reconsideration of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Palmetto-Leaves

by Mary Anna Evans

A Reconsideration of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Palmetto-Leaves

by Mary Anna Evans

|

It took a visionary to sit down in the 1870s and write, “Florida is peculiarly adapted to the needs of people who can afford two houses,” but Harriet Beecher Stowe established herself as prescient long before that. Her Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought the evils of American slavery into the cultural conversation, fostering popular support of the Civil War. For Stowe personally, Uncle Tom’s Cabin made her something almost unimaginable in her time—a woman made wealthy and famous by her own labor.

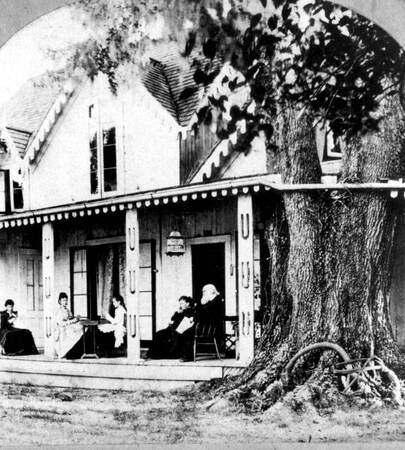

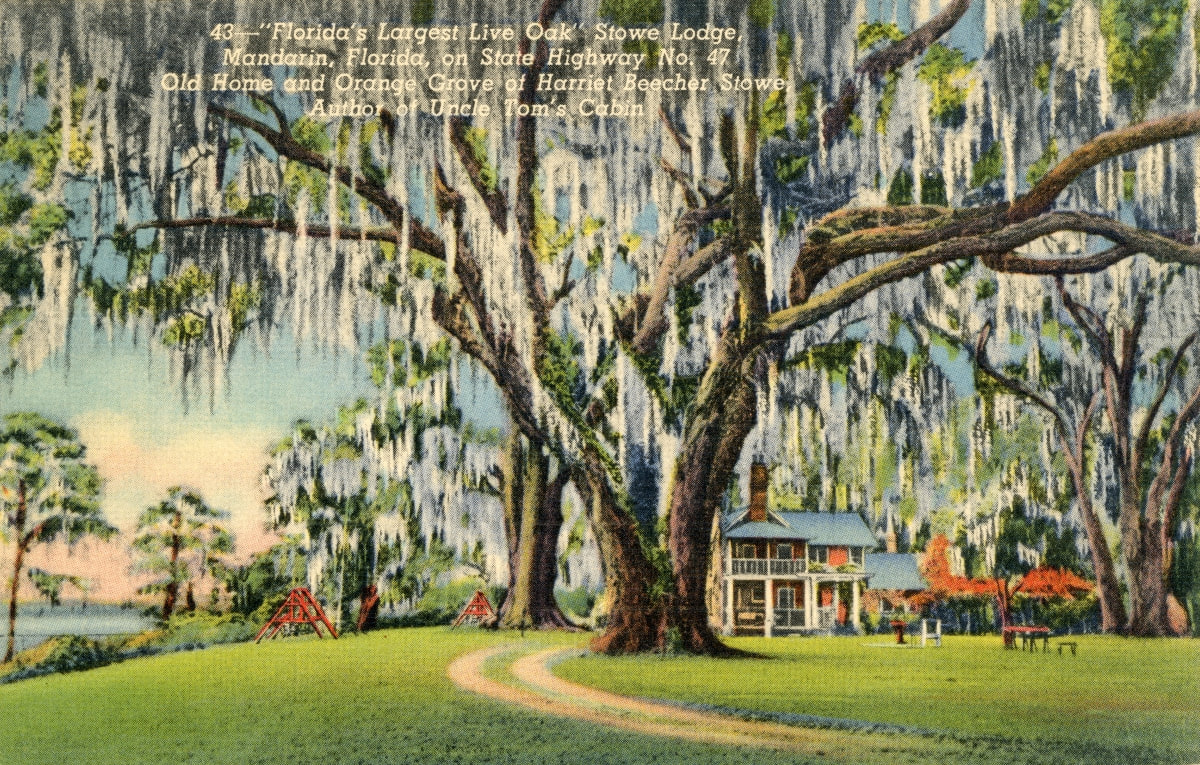

Calvin Stowe was a theology professor in Ohio and a widower when he married 24-year-old Harriet Beecher in 1836. He had warned his first wife that, “from my earliest youth my mind has been so entirely occupied by books that I have never learned the art of getting a living.” Calvin and Harriet Stowe went on to have seven children, and she began supplementing the family income with her pen years before the 1852 publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought financial security and, indeed, wealth. In 1866, Harriet made her first Florida real estate investment. In a sense, this was a consequence of the war; her son Frederic was a wounded veteran struggling with alcohol addiction, and she leased a cotton plantation for him to run, as a fresh start. Stowe became infatuated with Florida, buying a cottage in Mandarin across the St. Johns River from Frederick’s ill-fated plantation, which soon failed. In the ensuing years, she and Calvin took advantage of Florida’s suitability for people who can afford two homes, moving between Mandarin and Hartford, Connecticut. *

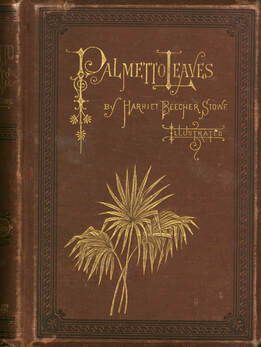

She promptly began writing essays about the wilderness outside her windows. Some of those essays became Palmetto-Leaves in 1873. Palmetto-Leaves was an early, important example of Florida narratives urging people to “Come on down!” She was careful not to promise unadulterated paradise, saying that “Florida, like a piece of embroidery, has two sides to it—one side all tag-rag and thrums, without order or position; and the other side showing flowers and arabesques and brilliant coloring.”

|

|

Still, her loving descriptions show that she adored life on the St. Johns. These passages are where Palmetto-Leaves shines. She saw orange trees as, “the best worthy to represent the tree of life of any that grows on our earth.” She made sand pine scrub sound like Shangri-La, even while describing it truthfully as “a dead sandy level, with patches behind them of coarse grass, and tall pine-trees, whose tops are so far in the air that they seem to cast no shade, and a little scrubby underbrush.”

Magnolia grandiflora, the southern magnolia, now grows far beyond its original range, but this was not so in the 1870s. To help her Northern readers visualize the unfamiliar tree, Stowe described it with the precision of a botanist: In front of this cottage, spared from the forest, are three stately magnolias, such trees as you never saw. Their leaves resemble those of the India rubber tree,—large, and of a glossy, varnished green. They are evergreen, and in May are covered with great white blossoms, something like pond-lilies, and with very much the same odor. The trees at the North called magnolias give no idea whatever of what these are. They are giants among flowers; seem worthy to be trees of heaven. If you’d never seen a magnolia tree, wouldn’t these words conjure one for you? And if you’d never seen a thunderstorm, wouldn’t reading about “a frown of Nature,—a black scowl in the horizon” bring you near enough to hear the wind howl?

*

I enjoyed twenty-six Florida springs before entering voluntarily exile. Stowe’s descriptions of springtime trigger an almost physically painful homesickness. When I read that the St. Johns “has looked all day like a sheet of glass. There is a drowsy, hazy calm over every thing,” I feel myself wading into water as warm as the summer air above its still, soft surface.

|

In this passage, she captures the evanescence of a Florida spring so vividly that I can only nod and say, “Yes, this is so.”

The gum-trees and water-oaks were just bursting into leaf with that dazzling green of early spring which is almost metallic in brilliancy. The maples were throwing out blood-red keys,—larger and higher-colored than the maples of the North. There is a whir of wings; and along the opposite shore of the bayou the wild ducks file in long platoons. Now and then a water-turkey, with his long neck and legs, varies the scene. There swoops down a fish-hawk; and we see him bearing aloft a silvery fish, wriggling and twisting in his grasp.

|

Time and again, she evokes the palmetto leaves of the title. Even today, amidst the encroaching highways and housing developments, palmettos persist where Stowe saw wilderness. When I read about her railroad trek to St. Augustine, I think I’ve glimpsed the coming of modernity, until I learn that horses towed her railcar on wooden rails. Perhaps she fanned herself with “…palmetto-leaves…pressed and dried, and made into fans…” while riding at a pace hardly faster than she could have walked.

The essays’ peaceful tone shifts into something more haunting when I reflect that many were written after her troubled son boarded a ship in 1871, sailed around the Horn, and landed in San Francisco. He never returned and the letters stopped coming. Stowe went to her grave hoping for word from her Frederick. She brought the convictions underpinning Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Mandarin, founding a church and school for freed slaves. She describes their lives in Palmetto-Leaves, lovingly at times, but her language and patronizing tone when referring to these African Americans grates on the modern ear, even as she is expressing admiration for them. Still, she was Harriet Freakin’ Beecher Stowe. By writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin and devoting herself to freedmen’s issues, she pursued justice for all. I’m interested in what she had to say, and I’m willing to squint at the occasional cringe-worthy statement. Others might feel differently, and that’s okay. Time passes and life is complicated. It says something about Stowe, I think, that she closes Palmetto-Leaves with another prescient statement: “In leaving this subject, we have only to repeat our conviction, that the prosperity of the more Southern states must depend, in a large degree, on the right treatment of the negro population.” |

*

Calvin’s declining health ended their travels south in 1884. He died in 1886 and Harriet died a decade later in 1896. Little physical evidence of their time in Florida remains. A historical marker marks the site of their cottage. The Mandarin Community Club occupies the Mandarin School that Harriet founded. A Louis Comfort Tiffany window in their honor, installed at Mandarin’s Church of our Savior, was destroyed in 1964 by Hurricane Dora, but fragments remain in the Mandarin Museum.

|

Scientists say that saw palmettos can be truly ancient, growing with excruciating slowness. Their stems sprawl and take root, forming clones that also grow slowly. These clonal patches can live thousands of years. It’s possible that visiting Harriet Beecher Stowe’s old haunts—Mandarin, the St. Johns, the former path of a wooden railroad—would accomplish the mind-bending task of showing me a palmetto whose leaves inspired a book that inspired the southward flood of people that, more than a century later, brought me with it.

I need to go to Mandarin and let my mind be bent. I need to listen when Harriet Beecher Stowe says, “Come down here once, and use your own eyes, and you will know more than we can teach you.” |

Mary Anna Evans is the author of the Faye Longchamp archaeological mysteries, which have received recognition including the Patrick D. Smith Florida Literature Award and three Florida Book Awards bronze medals. She is a former writer-in-residence for The Studios of Key West. Mary Anna holds a Master in Fine Arts in creative writing from Rutgers-Camden, but she also holds degrees in engineering physics and chemical engineering, and she is licensed to practice engineering in the state of Florida. She is an assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, where she teaches fiction and nonfiction writing. Her twelfth book, Catacombs, was published in August 2019. Learn more at her website.

|

Additional Reading:

“Ancient Saw Palmettos in the Heart of Florida,” 2017, In Defense of Plants. http://www.indefenseofplants.com/blog/2017/1/25/ancient-saw-palmettos-in-the-heart-of-florida Hedrick, Joan D. Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life. Oxford University Press, 1994. Klein, Shana. "Those Golden Balls Down Yonder Tree: Oranges and the Politics of Reconstruction in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Florida." Southern Cultures, vol. 23 no. 3, 2017, pp. 30-38. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/scu.2017.0025 Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Palmetto-Leaves. Osgood, 1873. Project Gutenberg. Web. Stowe, Harrier Beecher. Palmetto-Leaves, University Press of Florida, 1999. (ISBN 9780813034911) http://upf.com/book.asp?id=9780813034911 More information may be found via the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. |