Florida History

|

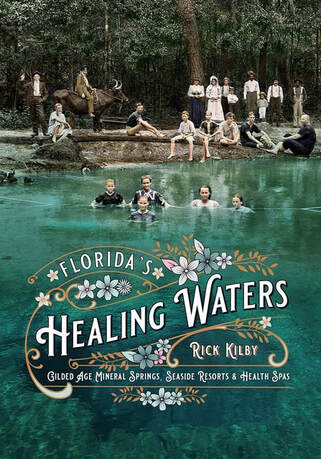

Florida’s Healing Waters: Gilded Age Mineral Springs, Seaside Resorts and Health Spas by Rick Kilby

(University Press of Florida, Paperback, 228 pp., $29.95) Reviewed by Bob Morison This is a beautiful book. Beautiful to look at, to hold, to thumb through its heavy, lightly glossed pages. University Press of Florida gave Rick Kilby’s Florida’s Healing Waters the generous treatment it deserves for its hundreds of photos and other images from the heyday of Florida’s mineral springs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when people flocked here to bathe in and drink the water. These include photos of the mineral springs with bathers in modest attire and of the verandas of grand hotels with patrons sporting the resort wear of the day – puffy blouses, long skirts, and fancy hats for women, jacket and tie and fedora or boater for men. There are vintage advertisements enticing people to take the waters to cure all that ails them and proclaiming the non-bathing amenities of the spa hotels: bowling, billiards, ballrooms, stables, hunting, fishing, casinos. Promised fine cuisine ran from shore dinners to tastes of home, Boston brown bread and baked beans. Kilby adds contemporary photos (many from his road trips) of some springs still in operation and others abandoned or paved over. At the heart of the book are chapters on the rise and decline of mineral springs in three areas: along the St. John’s river, in north Florida and the Big Bend, and along the Gulf coast, where patrons had a daily choice of mineral or salt water hydrotherapy. The St. John’s springs are the most iconic, running upstream from Jacksonville toward Orlando: Magnolia, Green Cove, Welaka, Orange, Ponce De Leon, Wekiwa, Alamonte. Kilby details the history of each spring, but the stories follow a pattern. Native Americans reveal the locations of springs. British or American settlers build plantations then rudimentary hotels for visitors. (But if you were hearty enough to make the trek in those days, you probably didn’t need to take the waters?) Among the early cure seekers was Ralph Waldo Emerson. The Civil War disrupted operations, and hotels served as local Confederate headquarters. Post-war, and now readily accessible by steamboat, the resorts expanded their facilities, activities, and marketing. They drew the leisure class from points north as well as literary luminaries (Harriett Beecher Stowe, George Bernard Shaw), business titans (Ford, Edison, Kellogg, Borden), and presidents (Grant, Cleveland). Most resorts thrived until the Great Depression, then the rise of competing destinations, saw their decline. Some survive today, but in many cases attempts to modernize polluted the waters or stopped the flow, and the springs were abandoned. In the heyday, medical (and perhaps hypochondriac) tourism flourished. No matter what ailed you, there was an app for that. The Fountain of Youth Bath House near St. Petersburg promised hot sulphur and salt baths as nature’s sure cure for rheumatism, neuralgia, and kidney, liver, and skin trouble. Dyspepsia and gastritis got a lot of play. The water at Magnesia Springs near Gainesville specialized in kidney and bladder complications. Some spas touted the precise chemical composition of their offerings, and it was the norm for the water to smell and taste foul, but only Punta Gorda’s has tested radioactive. Suffice it to say that the Sunshine State was hyping its waters long before they were packaged as swampland real estate. Surrounding chapters examine more things aquatic: the origins of recognizing the healing powers of water around the world, the opening of Florida’s wilds to tourists and cure seekers, Florida’s longstanding drinking water industry, the rising popularity of Florida’s beaches starting with Flagler’s in St. Augustine, and the practices of hydrotherapy since escaping the hucksterism. Kilby closes with a looking-forward chapter ominously titled “Population Booms and Algae Blooms.” Bad news about Florida’s current water usage and management notwithstanding, the tone of the book is fascinated and appreciative. From Kilby’s account of a visit to Warm Mineral Springs near Northport: I was a little giddy to be back in the water again. Or maybe, just maybe, Warm Mineral Springs really is the Fountain of Youth, and I was deliriously enjoying the effects. As I dog-paddled around the circular springs, I felt incredibly happy, unusually buoyant, and at peace while surrounded by dozens of health-seeking strangers speaking foreign languages. Would that we were all so appreciative of Florida’s waters. For more of Kilby’s aquatic adventures, see his Finding the Fountain of Youth: Ponce De Leon and Florida’s Magical Waters.

Bob Morison is co-author of What Retirees Want and Analytics at Work. He lives in Miami. More info at his website. Palm Beach, Mar-A-Lago, and the Rise of America’s Xanadu by Les Standiford

(Grove Atlantic, Hardcover, 319 pp., $29.00) Reviewed by Mary Anna Evans Marjorie Merriweather Post never thought small. When scouting 1920s Palm Beach for the site of a mansion to outshine all others, the cereal-heiress-turned-food-mogul sought permanence, something difficult to achieve on a low-slung coastal island with a dwindling stock of unoccupied land. In Palm Beach, Mar-a-Lago, and the Rise of America's Xanadu, Les Standiford ‘s description of her search gives a glimpse of old, wild Palm Beach: There were some slightly elevated, jungled tracts near the south end of the ancient reef that might fill the bill…but one would need vision to imagine a glorious structure placed on what now looked like forlorn scrubland a couple of miles from the center of town. Standiford provides an effective biography of Post alongside the history of Palm Beach promised in the title. He begins prior to Florida’s 1845 statehood, continues through railroad magnate Henry Flagler’s 1890s arrival, and finishes with Donald Trump firmly ensconced on the island.

Trump’s Mar-A-Lago, built by Post, ties past to present. More than three-quarters of the book passes before Donald Trump purchases it, and this purchase marks a schism in the narrative. Before, the book offers the vicarious thrill of watching the fin de siècle glitterati spend the money overspilling their pockets. After, the narrative shifts to the questionable financial shenanigans that Trump employed to acquire and keep it. Most will approach this book with curiosity about how wealthy people really live. (Is it really voyeuristic to be curious when consumption is this conspicuous? They want us to look.) Standiford deftly delivers well-researched stories of the uber-wealthy, from Henry Flagler’s wife Mary Lily, owner of a diamond-studded strand of pearls “as big as a Parrott’s egg” to Eva Stotesbury, whose pearls hung to her feet. Their husbands’ money transformed Palm Beach into something baroque, ornate, almost fevered. Standiford doesn’t shy away from the dark side of this fever dream. Wives of robber barons do not often end well. Henry Flagler’s first wife died in childbirth in 1881. His second wife was committed in 1899, spending her last thirty-three years in an insane asylum. He married third wife Mary Lily of the Parrott’s-egg pearls weeks after his 1901 divorce. Widowed in 1919, she married a gold-digging judge and died under mysterious circumstances months later. Eva Stotesbury, heiress to Mary Lily as doyenne of Palm Beach, understood the instant social status that comes with money. She had lived forty-some-odd years before marrying rich. Standiford captures her self-deprecation in two scenes. In one, Eva responds to disapproval of her attire: “Pearls in the daytime?” sniped the matron, only to be met with Eva’s smiling riposte. In another, Eva interrupts businessmen’s bragging:

“My only astute business move,’ she said, ‘was marrying Even more than Eva Stotesbury, Standiford paints Marjorie Merriweather Post in a flattering light. Though Palm Beach glittered with the jewels of the wives of wealthy men, Post and her Mar-A-Lago glittered most brightly of all. Her marriages ended no more happily than Henry Flagler’s, but she didn’t just survive them. She ended them on her terms, while overseeing her father’s Postum Cereals, which gave us Grape-Nuts and a cultural predilection for cold cereal at breakfast-time.

Standiford provides the perfect anecdote to demonstrate her business acumen. After a shipboard meal of particularly succulent duck, Post learned the chef’s secret: it had been frozen by a method invented by a man named Clarence Birdseye. Her directors discouraged her from entering the frozen food market in an era before widespread home refrigeration, but she persisted for years. When Postum finally bought Birdseye’s operation, Postum was transformed into the behemoth General Foods. But even the most formidable women don’t live forever. Post spent years trying to save her inexpressibly expensive home Mar-A-Lago from the wrecking ball, dying in 1973 with its fate still in question. Enter Donald Trump. The book’s tone shifts abruptly with Trump’s 1985 purchase of the estate, detailing the financial machinations he used to drive down the price, drive down his taxes, and convert the property to a private club. The contrast is stark between these hard-nosed tactics and the languorous old guard, whose status depended on the illusion that money flowed like water. This book is recommended to those interested in Trump’s role in the fantasy world of Palm Beach society, but it will be of even more interest to readers curious about how that world came to be. Mary Anna Evans is the author of the Faye Longchamp archaeological mysteries, which have received recognition including the Patrick D. Smith Florida Literature Award and three Florida Book Awards bronze medals. She teaches fiction and nonfiction writing at the University of Oklahoma. Learn more at www.maryannaevans.com Hotel Scarface: Where Cocaine Cowboys Partied and Plotted to Control Miami by Roben Farzad

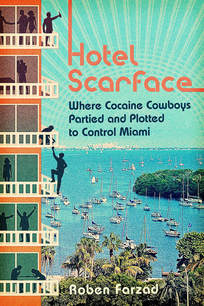

(New American Library, Hardcover, 332 pp., $26.00) Reviewed by Bob Morison In the early 1980s, when Miami was the capital of cocaine, murder, and illicit cash flow, the Mutiny hotel and club at Sailboat Bay was the place to conduct the business of drug dealing, as well as partake of all attendant debauchery. Roben Farzad introduces the Mutiny as “a fantasyland for outlaws in the hellscape that was Cocaine Miami” and “a criminal free-trade zone of sorts where gangsters could both revel in Miami’s danger and escape from it.” The Mutiny was a lucrative operation. Each of its 130 rooms and suites had its own name and elaborate thematic décor: Marakesh (sic), Singapore, Lunar Dreams, and the all black Midnight Express. In the club, “Mutiny Girls” poured Dom Perignon nonstop. Outside, valets parked Bentleys. Tipping was heavy. The members’ dress code included Rolex, beeper, cowboy boots, and a leather bag containing at least ten thousand dollars in cash and a .380 Walther PPK semiautomatic, “the sidearm of choice for the discriminating 1980s cocaine dealer.” At 2951 South Bayshore Drive in Coconut Grove, the Mutiny was about a quarter mile as the crow flies from Miami City Hall. In the Introduction to Hotel Scarface, Billy Corben and Alfred Spellman (producers of the documentary series Cocaine Cowboys) call the Mutiny “the Rick’s Café of Miami.” It certainly attracted the usual suspects: cocaine kingpins with their girlfriends and lieutenants, the bankers who laundered their money, the lawyers who tried to keep them out of jail, and even some of the cops trying to put them in. Plus the see-and-be-seen celebrities: Paul Newman, Burt Reynolds, Sally Field, Ted Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Al Pacino while filming bits of Scarface, and Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas while filming Miami Vice. At the Mutiny, everybody crossed paths with everybody. In a chapter on Raul Diaz, the most persistent, improvisational, and successful of the cops, Farzad gives a nod to the entanglements: “Diaz had been hooking up with Nancy Cid, ex-wife of Juan Cid, the prolific pot dealer. Juan Cid’s attorney was none other than Douglas Williams. Douglas Williams was also representing the bodyguard of Amilcar, Raul Diaz’s prize catch, when he wasn’t busy grilling Ricardo Morales, Raul Diaz’s start asset. (No use using a Venn diagram.)” In Hotel Scarface, it’s hard to tell the players even with a scorecard, or in this case, the cast of characters list preceding the first chapter. They bounce in and out of the short chapters Farzad uses to piece together individuals’ stories and chaotic events. The reader needn’t try to keep track of everything—just go with the splashing flow and patterns will emerge. They try to eliminate each other. Everybody eventually gets arrested. Almost everybody cops a plea and rats out his associates. And yet they’re still pals. Rat and rat-ee embrace in a prison hallway. The first big drug trial falls apart when the star witness exchanges salutes with the defendants on his way to the stand. The Cuban drug lords had donned the mantle of the legendary Mafiosi who did business and pleasure in South Florida a half century earlier, and the book’s title refers to the Mutiny’s serving as the model for the Babylon Club in the 1982 remake of the gangster film Scarface. Most of the filming was done in LA, however, because Miami’s civic leaders disavowed the connection, lest Cuban Americans be cast in a bad light. But the local news shed plenty of bad, if strangely entertaining, light. One of the biggest busts was of Jose “Coca-Cola” Yero, high-volume trans-shipper of coke to Miami via the Bahamas. In addition to one ton of cocaine, “agents seized two Lamborghinis, three Benzes and a dozen Rolex watches color-coordinated to his suits. . . He told police he was just a boat mechanic.” At the heart of the narrative are “Willie” Falcon and “Sal” Magluta, a.k.a., Los Muchachos. The Miami Senior High dropouts started big (a 30-kilo shipment), ramped up fast, and inherited the direct connection to the Medellin cartel and a choice table on the Mutiny’s Upper Deck. One of their pilots described the business model: “They were more like smugglers who were diplomats, salesmen and CEOs. It was like they were overseeing a conglomerate.” A conglomerate that “invested good money and time in the best boats, planes, trucks, attorneys, accountants, bodyguards, mules and corruptible politicians and cops.” Arrested in 1991, Willie and Sal successfully tampered with the jury of their 1996 trial but lost the rematch in 2002. Sal was defiant and painted as the brains of the outfit. He got 215 years. Willie copped a plea and got 20. And the Mutiny? Under threat of prosecution for various shortcomings, the owner was forced to sell at the top of the market in 1983. Then things went downhill, and ownership transferred to the Feds when the hotel’s main banker was sent away for 20 years. It was shuttered in 1989. (Ed Note: It is again operating as a hotel as of the posting of this review.) Farzad is too young to have Mutinyed first hand. He became fascinated with the place as a local teenager after an encounter with an old member. Nearly 100 interviews and many kilos of other research later, he’s captured a time and place thankfully not to be seen again. The book features a photo array including the principal characters, a bevy of Mutiny Girls, a gold Mutiny membership card, and a representative scene captioned, “Murder victim in trunk, Miami, 1981.” Bob Morison is co-author of Workforce Crisis and Analytics at Work. He lives in Miami. More info at his website. Making Modern Florida: How the Spirit of Reform Shaped a New Constitution by Mary E. Adkins

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 241 pp., $29.95) Reviewed by Natalie Havlina “Florida’s 1966 Constitution is sometimes ridiculed for its malleability. Who, after all, would design a document in which pregnant pigs are given civil rights?” asks Mary E. Adkins. In her new book, Making Modern Florida: How the Spirit of Reform Shaped a New Constitution, Adkins answers this question by telling the story of how Floridians adopted our present constitution “to meet the needs of a space age society.” Adkins begins by exposing the preceding,1885 Constitution, as “a document of the people of its time— if one counts only white men as ‘the people.’” An 1885 relic of the Reconstruction era, Florida’s constitution was ill-equipped to govern the rapidly growing and changing population of a diverse state. Among other problems, the “horse and buggy constitution” enabled some of the most extreme malapportionment in the country, resulting in a legislature that grossly overrepresented rural North Florida and gave little voice to the growing urban population of South Florida. Attempts to rewrite the constitution in the 1940s and 50s failed. Enter the US Supreme Court. Beginning in 1962 with its decision in Baker v. Carr, the Court began cracking down on malapportionment. These decisions contributed to the era’s “spirit of reform” and laid the foundation necessary for a new Florida Constitution. The Florida legislature took up constitutional reform again in 1965 by creating the Constitution Revision Commission. Over the course of 1966, this thirty-seven member body drafted a new constitution that was later debated, revised, and passed by the legislature. The people ratified the new Constitution in 1968 and it has governed Florida ever since. I recommend Making Modern Florida to fellow attorneys, political enthusiasts, civil rights devotees, and any civically-minded Floridian who has ever lamented Florida’s more novel constitutional provisions. Adkins does an admirable job explaining the issues, both substantive and legal, in plain language. She also adds humor and humanity to the narrative by including cameos of the main players and colorful anecdotes, such as the politically powerful Pork Chop Gang’s 1955 blood oath and future-governor Reuben Askew’s ill-fated attempt to conquer insomnia during the 1965 special session. Do be prepared to do some skimming. Readers will have different levels of interest in the nuts and bolts of the constitutional revision process. In addition, Adkins lists a number of details in the main text that would be better consigned to the endnotes. Nevertheless, the knowledge and insights to be gained from Making Modern Florida are well worth the effort. Natalie Havlina is a former federal law clerk and public interest environmental litigator. She is now pursuing graduate studies in fiction at Florida International University. Marjorie Harris Carr: Defender of Florida’s Environment by Peggy Macdonald

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 258 Pages, $26.95) Reviewed by Lauren Rivera Peggy Macdonald has written an engaging biography of Marjorie Harris Carr (1915-1997), one of the three Florida Marjorie(y)s—including Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Marjory Stoneman Douglas—who used the power of the pen to bring awareness to the precarious state of natural flora and fauna, which provide a glimpse into what Florida originally looked like.To boot, it’s a fascinating history of the environment and gender politics in Florida, a detailed chronicle of an extended legal battle between environmentalists and the Army Corps of Engineers, as well as a daring and tender love story. Macdonald’s overview of Carr’s life and the obstacles to her many achievements in the introduction sets our expectations high. And we wonder, just how did Carr face institutionalized gender discrimination, transform the modern environmental movement, and raise five children in one lifetime? Primary sources give Carr’s life the vivid detail that makes this book such a pleasure to read. For instance, Chapter 2 “Blending Science and Romance in the New Deal Era,” is endearing and romantic. In 1937, she eloped with Archie Fairly Carr II, a struggling graduate student at the University of Florida who was still tied up in Gainesville, writing his dissertation, and unable to support his young wife on a paltry stipend. The couple agreed to live apart out of economic necessity, and they kept the marriage secret, because Marjorie (still going by Harris) would have been expected to resign under New Deal ordinances as she was starting a new position as a laboratory technician and field collector at the Bass Biological Laboratory and Zoological Research Supply Company in Englewood, Florida. Macdonald uses the long-distance love letters, collected and shared with her by the Carrs’ first-born daughter, Mimi Carr, to underscore the tension, anxiety and pain that tried her parents’ relationship. Their secret marriage was wrought with misgivings about their choices to live separately and devote themselves to science. Their words demonstrate their passion for scientists and each other: “Your earthly loveliness is as stable and indomitable as a rainforest,” wrote Archie to his love, and he imagined that at the moment of his death, “When the last electrons of the last atoms that have been me fly out of their orbits it will be in quest of you.”

Lake Alice, Gainesville, FL. In 1969, Marjorie Harris Carr and colleagues from the University of Florida challenged UF President Stephen C. O’Connell and FDOT plans to drain and replace Lake Alice with a 2000-car parking lot. Photo source: University of Florida Library, http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/ufarch/lakealice.htm

Macdonald effectively contextualizes Carr’s moral crusade as a devotee of flora and fauna in post World War II Florida, where progress and industry ruled the day, at the expense of the environment. Carr worked her way from local causes to state-wide activism, serving as a catalyst, Macdonald writes, in the “transition from conservation—or the idea of preserving nature for humanity—to environmentalism, whose goal was to protect nature from humanity.” Rigorous and tenacious, Carr forged her own brand of activism, using her M.S. degree in zoology from the University of Florida to publish her ongoing research on bass, moccasin, or the Oklawaha River, harnessing the clout of editorial teams on major Florida newspapers to gain support for her views. Yet when it was more effective, she was willing to play the part of a demure housewife. Some legislators, such as state senator Bob Graham, only knew her as Mrs. Carr, Archie’s wife.

Macdonald argues that, “Marjorie stands in contrast to certain interpretations of women’s environmental activism in the late twentieth century,” refuting historian Robert Gottlieb’s distinction between male and female leadership roles and pointing out that his view overlooks Florida campaigns and leaders. “Using Gottlieb’s model for female and male leadership styles as a guide, Carr’s style would have fallen into the ‘masculine’ category—like most of the other women leaders of the early environmental movement—because she emphasized science, economics, and politics over traditional women’s concerns.” Macdonald illustrates Carr’s influence as a founding member of Florida Defenders of the Environment (FDE): A state legislator once claimed that Carr's mere presence at the Florida State Capitol persuaded legislators to take action on the barge canal issue. "All you have to do is walk the halls," the legislator told Carr. "You don’t have to say a word. Just be seen there, and every legislator who sees you will say to himself, 'Oh, yes. The Barge Canal.'" Macdonald’s inclusion of quality photographs reproduced in grayscale partly satisfies the desire to “see” the places mentioned throughout the text. Those who want to visit and see the Florida places she saved, can, and Macdonald’s biography shows us how she did it.

For me, it is especially satisfying to read about a woman who had the passion and knowledge to motivate and inform citizens of this planet who grew up without environmental consciousness as part of their curriculum in schools, the message sent through children’s films, or the reason for recycling programs in their neighborhoods. Macdonald’s biography of Carr compellingly illustrates her life-long fight. Lauren Rivera, a native of Miami, received her MFA in Creative Writing from Florida International University. Gainesville is the new setting of a growing family, teaching secondary Language Arts, and plenty of reading and writing Digging Miami by Robert S. Carr

(University Press of Florida, 296 pp., $29.95) Reviewed by Jan Becker In a city like Miami, whose growth over the past century has been primarily vertical, it is easy to forget one is walking on ground that has been tread on for more than ten thousand years. In Digging Miami, Robert S. Carr, Miami-Dade County’s first archaeologist and executive director of the Archaeological and Historical Conservancy, directs his readers’ attention towards the subterranean history of Miami as told through the artifacts found during planned excavations and often accidentally during construction. The book provides the reader with a unique vision of the past easily overlooked on a stroll through the streets of the Magic City. Much of Digging Miami is a catalogue of ancient trash heaps and bone yards. For the archaeologist, it is fortunate that inhabitants of Southern Florida have been dumping their garbage for thousands of years, because refuse heaps yield the clues needed to recreate the past. While archaeological research has been conducted in South Florida since the late 1800s, the earliest excavations were not done with a great deal of care in preserving or cataloguing the artifacts found. More modern methodology only began to be employed in the early 1980s, so one can assume there is still a lot left for the ground to yield. The book is structured so that the reader progresses from the very earliest fossil records, before humans first came to South Florida, through different waves of settlement beginning with those who migrated from Siberia, then the Florida Indians, Tequesta, Seminoles, Spaniards, and into the more recent waves of immigrants who developed the region beginning in the 19th century. Much of the book is technical in nature, explaining how digs operate and cataloguing the findings. The writing is tedious in places, as one could expect from a study of shell tools and decorative patterns on pottery shards. However, these passages are necessary to understand what archaeologists find that might not catch the eye of an average pedestrian, and the technical material is tempered with surprisingly lyrical passages. Carr’s description of the modern Miami skyline feels more like poetry than prose: “Towering buildings bite into the sky and a million artificial lights dim the sea of stars that once hugged the earth’s horizon.” The ease with which a wrecking ball can ruin a potential site of excavation is shown in the 1897 destruction of a fifteen-foot high burial mound at the mouth of the Miami River. Construction crews building the Royal Palm Hotel leveled the mound, not to make room for the hotel’s foundation, but to ensure hotel guests sitting on the veranda would have an unobstructed view of Biscayne Bay. Carr includes documentation from the foreman of the clearing crew, John Sewell, who wrote that all they found were a few “trinkets.” However, Carr chillingly claims that between fifty and sixty skulls were recovered and given away and that, “Many skulls made their way to the Girtman Brothers general store, where they were reportedly sold as curios to visiting tourists.” Throughout the book, Carr gives examples of this kind of skullduggery. Carr’s work as an archaeologist requires extreme diligence to ensure that we do not lose artifacts that lie under the foundations of buildings currently being leveled to make room for more modern structures. When I began reading, I hoped to learn more about the forgotten Lemon City Cemetery in Miami that was rediscovered in 2009 after bones and coffin fragments were unearthed during demolition of a YMCA to make room for low-income housing. Local historian Larry Wiggins was able to locate the death certificates of 523 deceased people, all of whom were black, 70% of whom had come to Miami from the Bahamas or were of Bahamian descent. Of the 523 reported burials, only 20 sets of bones have been recovered. Others were either moved by family members when the cemetery was abandoned or ground into what became the foundations of the YMCA building. The housing project plans were altered to preserve the cemetery site, and a memorial has been erected, but the bones are still waiting to be reinterred in a final resting place, and very little is known about the people to whom they belonged. Carr explains that those who did the physical work of building Miami were often forgotten, or buried where it proved to be most convenient: “Some reports indicate that laborers who worked on railroad construction gangs and died during service were unceremoniously buried in solution holes along the railroad tracks.” Reading Digging Miami, I was surprised at how thoroughly I was affected by a newfound understanding of how vulnerable the relics of the past are to modernity’s machinery. Carr explains that historical preservation is important, “because it defines us as a civilization and a community. We connect to our history because it reveals a deeper part of who we are and who we should not be.” I find myself walking more gingerly through the city these days, more mindful that under the asphalt and macadam lie the bones and belongings of people who lived here and died with no markers to indicate their presence. Jan Becker lives in Florida. Her writing has appeared in Sliver of Stone Magazine and is forthcoming in The Circus Book, Emerge, and Brevity Poetry Review. |

Roaring Reptiles, Bountiful Citrus, and Neon Pies: An Unofficial Guide to Florida’s Official Symbols by Mark Lane

(University Press of Florida,Hardcover, 152 pages, $19.95) Reviewed by Nicholas Garnett As anyone who lives here can tell you, Florida suffers from one hellacious identity crisis. Head north, away from South Florida’s teeming multi-lingual, multi-cultural mashup and, before you know it, find yourself in a rural Nowheresville, set in the middle of The Land That Time Forgot. The contrast is not only urban vs rural. Florida’s economy is boom and bust, its politics split evenly, if not uniformly, red and blue. Florida’s legislators, charged with managing the state’s affairs, have tried their best to impose some sense of identity upon the mayhem. The results, as Mark Lane, the author of the funny and insightful Roaring Reptiles, Bountiful Citrus, and Neon Pies, points out, have ranged from mixed to all-mixed-up. Lane, a Central Florida native and a columnist and feature writer for the Daytona Beach News-Journal, surveys nineteen of the State’s official symbols that range from the wacky to the woeful. Unlike the proclamations about which he writes, Lane does not take himself too seriously. In his foreword, entitled a “Helpful Letter to School Librarians,” Lane dispels the notion that his book is intended to be a serious reference guide. “Sadly,” he writes, “this is not that book. It’s full of the kind of unnecessary commentary that might cause trouble.” If by “trouble” Lane means laying bare the inherent weirdness of the third most populous state in the country, he is correct. Lane devotes each of the book’s chapters to one state symbol he has deemed worth of examination. The first, Florida’s official dessert, the Key lime pie, is a story of contrasts and contradiction. Even the taste blends the tart and the sweet. Then, there is the matter of the pie’s main ingredient, the Key lime, which no longer comes from Florida. Lane tell us that Key lime production, wiped out by hurricane Andrew, has been replaced by limes from Mexico. Yet the immense popularity of the dessert, combined with its identification with Florida, elevated it to state-symbol worthiness, though, as Lane points out, it took the proponents of Key Lime till 2006 to prevail in their “pie fight” with North Florida legislators, who favored the Old South delicacy, pecan pie. In Florida, even the obvious can take a while to be recognized. The state’s official nickname, the “Sunshine State,” seems like a no-brainer. However, Lane reveals that it was 1970 before the legislature made the slogan official, putting an end to other, considerably less zingy proposed nicknames such as the Peninsula State, the Everglades State, and even the Alligator State. Here, Lane pauses to dig into—and at—the enigma that is Florida: Yes, we are also a bright spot for crime, drugs, poor mental hygiene, political craziness, state and municipal corruption, heedless driving, poorly maintained infrastructure, underfunded schools, environmental destruction, sinkholes, lightning, hurricanes, sharks, and pythons . . . but damn, it’s nice and bright outside. Even in February. Ouch. But you can’t say Lane didn’t warn the school librarians.

Subsequent chapters present symbols that range from the predictable (the official fruit, the orange), to the unexpected (the official bird, the mockingbird) to the bizarre (the official state fossil, the Eocene Heart Urchin). And then there’s the downright embarrassing. Florida’s state song, “Old Folks at Home” also known as “Swanee River,” was written in 1851 by Stephen Foster and adopted as the state song in 1935. The song, which pined for the good old days of the Old South, included the cringeworthy line “Oh, darkies, how my heart grows weary . . .” In 2007, Governor Charlie Crist found the spirit of the song, not to mention the lyrics, so embarrassing that he broke with tradition and eliminated it from his inauguration ceremony. The Florida Music Educators Association ran a contest to find a replacement, but, in a compromise in 2008, the state legislature adopted the winner, "Florida, Where the Sawgrass Meets the Sky," as the state anthem, while “Swanee River” with some cleaned-up lyrics, remains the state’s official song to this day. Lane never misses a chance to stick it to Florida, but he does so with the earned perspective of an insider. He ends his book by recounting his childhood as the son of a NASA Apollo engineer, a transplant from Upstate New York, who “latched on the Florida Dream hard.” Part of that dream was an optimism that man would walk on the moon. Another part was that he could live in a warm, sunny place surrounded by natural wonders to be explored. That sense of wonder has stayed with Lane, who writes: At heart, I still see the state as one big roadside attraction crawling with monkeys and alligators and perfumed with flowers the size of dinner plates. All of which, based on what Lane has told us, have legitimate shots at become future official state symbols.

In fact, by the time we reach Lane’s hilarious afterword, a facetious proclamation designating the flip-flop as Florida’s official footwear, we may be tempted to proclaim that, in Florida, the question is never why. It’s why the hell not? Nicholas Garnett's writing has appeared in Salon.com, R-KV-RY Quarterly, Sundress Publication's Best of the Net; Tigertail, A South Florida Poetry Annual, Best Sex Writing of 2013, and All That Glitters (Sliver of Stone). He is co-producer of the Miami-based storytelling series, Lip Service: True Stories Out Loud. The Corporation: An Epic Story of the Cuban American Underworld by T.J. English

(William Morrow, Hardcover, 592 pp. $28.99) Reviewed by Victoria Calderin In The Corporation: An Epic Story of the Cuban American Underworld, author and journalist T.J. English weaves historical accounts of the Cuban Mafia with details of the lives of those involved to recreate a vivid, dramatic world. English, who previously authored Havana Nocturne on the influence of the mob in Cuba, has now written about the inverse relationship, the influence of a Cuban on the mob, focusing on Jose Miguel Battle Sr. and The Corporation, the criminal empire he created and ran in New Jersey, New York, and of course Florida. Battle, who bet on the CIA’s plans to remove Castro from power as did many other Cuban expats, ended up losing his bet. Unlike those who walked away from the table after losing, he decided to go all in and use what he knew from serving on the police force in Cuba and later being trained by the CIA to birth The Corporation. The first chapter opens in April of 1961 with Battle among the American-trained Cuban forces of Brigade 2506 attempting to overthrow Castro at the Bay of Pigs. The second chapter jumps a year and a half and bring us to Miami to see President Kennedy address the broken remnants of the invasion: It was an overcast day on December 29, 1962, when President Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline, were driven into the stadium in a white convertible. The cavernous Orange Bowl was filled nearly to capacity with forty thousand people. [. . .] A platform had been set up at the fifty-yard line, with a podium adorned with the presidential seal of the United States. Before stepping to the podium, Kennedy greeted a line of brigade members, some of whom were missing limbs and others on crutches. [. . .] The entire audience rose to its feet, cheering wildly, with shouts of ‘Guerra! Guerra!’ and ‘Libertad! Libertad!’ Some of the brigade members had tears in their eyes. Such jumps in setting and use of loose chronological order continue though the book. English's structure allows him to focus on and explore the stories of many people connected to Battle directly or tangentially, such as Ernestico Torres, one of Battle's protégés, as well Idalia, Ernestico's girlfriend. You get to see Ernestico and Idalia, among other accomplices, cross Battle, go on the run, and be killed on Battle's orders. You also get to know Julio Ojeda, "a Miami detective with an impressive resume," who travels to New York to aid in Battle's arrest, takes part in Battle's trial in Miami, and ultimately goes on to be indicted himself.

The striking detail English brings to each passage reveals the thoroughness of his research. For example, in this excerpt Battle is talking to Mujica, a fellow member of Brigade 2506, after Mujica has met with him to request independent control of some gambling spots in Miami: “Then you agree,’ said Mujica. ‘I’m free to have my bolita holes and stay in business.’ The reader who wants to know more about English's research can check out the impressive thirty-six pages of notes.

And readers should be warned that there are a few graphic images of crime scenes and mugshots, as well as floor plans and images of many of the people involved in the story. As you would expect of any history of mobsters and gamblers, there is also a whole lot of colorful language in English and Spanish. If you were a soldier on the battlefield, say, a brigadista pinned down behind enemy lines at the Bay of Pigs, having a platoon mate with cojones could be the difference between life and death. Instinctively, that platoon mate attempts to come to your rescue, because a person with big balls does not wither in the face of risk. He does not care about the odds. He acts. Duty calls. He takes that chance because he has big balls. In any given situation, there is normally a fifty-fifty chance that a person will have made a wrong choice. Having big balls has little to do with intelligence. Sometimes the guy with an excess of moxie is the dumbest guy on the block. English’s style made even someone like me who is familiar with a lot of this history feel like I was diving into new and dark tales of one Jose Miguel Battle Sr. and his world, rather than reading the same stories yet again. He takes a complicated and nuanced story of crime and politics and gives you an amazing read.

Victoria Calderin is a Miami-based writer and MFA candidate at Florida International University. Utopian Communities of Florida: A History of Hope by Nick Wynne and Joe Knetsch

(The History Press, Paperback, 165 pp., $21.99) Reviewed by Natalie Havlina In Utopian Communities of Florida: A History of Hope, authors Nick Wynne and Joe Knetsch describe eleven Florida settlements established between the 1790s and the 1930s that sought to create, not a perfect society in the sense of Thomas More’s Utopia, but an improved society. Though the communities differed in a number of ways, their participants shared the belief that, “they could alter the flow of culture and create a better world.” Some of the communities discussed in the book were based on religious ideals. A colony for Catholics was established in San Antonio in the 1820s, a safe haven for Jews north of Micanopy in the 1880s, and a permanent camp of Spiritualists in Volusia County in the 1890s. More secular ideas motivated other groups. The principles that drove Cyrus Teed and his followers to found the Koreshan Unity settlement in Estero in the 1890s combined religion with philosophy and science, while the Chautauquans retreat at Defuniak Springs became an “intellectual center” during the early 1900s. Yet other colonists were motivated by the hope of survival. Eleven hundred indentured servants, mainly farmers from Minorca on the verge of starvation after a three-year drought, came to settle the New Smyrna colony on Mosquito Inlet. Likewise, economic hardship brought people to Withlacoochee, Escambia Farms, and Cherry Lake Farms, three cooperative communities planned by the federal government as part of the New Deal. The book presents each community in a separate chapter that begins by placing the group in its historical context and ends with a description of the colony’s ultimate fate. Some of the communities evolved into other entities. The Catholic colony in San Antonio, for instance, became a Benedictine abbey, while Melbourne Village, Crystal Springs, and Defuniak Springs are “viable towns” today. Other settlements failed dramatically. Moses Levy’s Pilgrimage Plantation never attracted enough settlers to begin with, and the continuation of New Smyrna became impractical after one group of its colonists mutinied and a second fled to St. Augustine to escape the harsh treatment of their overseers. The Yamato Colony, a community of Japanese immigrants near Boca Raton, “disappeared entirely” when the federal government used its powers of eminent domain to appropriate the Yamato lands in 1942, even though the colony’s inhabitants were so well-respected by their neighbors that not a single citizen of Yamato was interned during World War II. Utopian Communities of Florida also delves into the backgrounds of the idealistic, and frequently charismatic, individuals who founded the communities. The authors actually devote more space to Cyrus Teed and the development of his ideas than on the Koreshan Unity Teed established at Estero. The book describes the life and philosophy of James Cash Penney, “a man of action with a growing ambition that grew more aggressive as he accumulated more wealth.” After building the J.C. Penney Company department stores to great success in the 1920s, Penney established the experimental Penney Farms near Green Cove Springs, “to try out his ideas of scientific management of farms and a cooperative arrangement for profit sharing.” He was forced to abandon the Penney Farms project when he suffered “huge losses” in the Great Depression. Wynne and Knetsch pack a lot of information into a short book and their style can be quite dry, as they focus on educating their readers, rather than entertaining them. Black and white photographs of the communities, their founders, their members, and, in the case of New Smyrna, their ruins, do help bring the history to life. Those with a particular interest in idealistic communities or the history of settlement in Florida will find Utopian Communities of Florida a compact work of scholarship with some interesting information. Natalie Havlina is a teaching assistant in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Florida International University and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. Prior to coming to FIU, Havlina spent a decade practicing public interest law in the Northwest. The Allure of Immortality: An American Cult, a Florida Swamp, and a Renegade Prophet by Lyn Millner

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 360 pp., $24.95) Reviewed by James Barrett-Morison Today, we often think of cults in terms of their isolation from regular society: odd beliefs, odder practices, and policies like disconnection from friends and family members. At first glance, the Koreshans, the late 19th and early 20th century religious movement featured in The Allure of Immortality, seem to follow the same trend: an eccentric leader, Dr. Cyrus Teed (who names himself Koresh after a religious vision), who claims to be a Messiah and predicts the end of the world; a following which lives in collective housing, hiding itself from reporters; and repeated moves, from upstate New York and San Francisco to Chicago and eventually to swampy Estero, Florida. But rather than being an isolated cult, the Koreshans were tied in with politics and society, first in Chicago, where they intersected with the suffragette and labor movements, and later in Estero, where they became intimately bound up in the nascent politics of Lee County. They also advertised heavily and ran a successful printing business for decades. Much of what the public knew about the Koreshans focused on their quirky religious beliefs. Lyn Millner doesn't linger on or sensationalize these, focusing instead on how they affected the movement's workings and external relations. Equality of the sexes drew women to the movement—women outnumbered men from the moment Teed set up shop in Chicago in 1886—and prompted rumors, lawsuits and threats from their spurned husbands. The related goal of "breaking the family tie," showing no particular regard for parents, siblings, or children, shaped hierarchy and organization within the Unity, the Koreshans' organizing body. The goal of strict celibacy was shared with similar communities like the Shakers, and helped Teed forge alliances with them, as did their practice of collective living and staunch opposition to Gilded Age capitalism. The Koreshans' most particular and famous belief is the hollow Earth theory. Millner explains it thus: "Imagine peeling the paper map off an old-fashioned school globe, slicing the globe open, then pasting the map inside. . . At the center of the globe is the entire cosmos." China, Teed said, was separated from America not by the Earth, but by the heavens. Rather than focusing on the scientific particulars, Millner discusses the hollow Earth theory in the context of a long and expensive Gulf beach encampment that Teed and followers conducted in an attempt to prove themselves right. The Koreshans' theories and practices drew ridicule from the press, a powerful force in the late nineteenth century. The press is, in fact, one of the main characters in the book. Teed's relationship with journalists, who would frequently publish inaccurate and sensationalist stories, was always tense and sometimes downright hostile. When confronted by a reporter, one Koreshan said, "You newspapers may sneer all you like, but the time's coming when you will tremble. The end of the world is at hand. Other folks fear it. We know when it will be here." Where other movements crumbled under the harsh light of yellow journalism, the Koreshans were steadfast, even after repeated scandals, migration across the country, and even Teed's death, when their expectation of his resurrection failed grotesquely. Millner writes that she found it difficult at first to get inside the mind of Cyrus Teed, in part because his writings, convoluted and esoteric even in personal letters, contrast sharply with descriptions of him as a quiet but charismatic and hypnotic man. How could a doctor from New York convince hundreds of believers to follow him to the most remote corner of Florida, to set up a city with nothing but their bare hands? But over the course of the story, Millner captures Teed's power and the committed faith of his followers becomes clear. For a book of historical nonfiction, The Allure of Immortality contains numerous downright thrilling moments. A low-speed foot chase, in which a constable and an attorney, seeking to arrest Teed and co-leader Victoria Gratia, chase after them across Chicago and onto a train, had my heart pounding. And a brawl over a misheard phone call in the sandy streets of Fort Myers between then-sixty-seven-year-old Teed, a hotelier, the town marshall, and several others acts as a turning point in both the prophet's life and the politics of Lee County. Throughout, Millner's writing is historical journalism at its finest, combining a refusal to bend the facts with beautiful and enthralling prose. This is perhaps most evident in her depiction of Estero, an almost magical place where: there were so many fish in the shallows that the bottoms of their skiffs rumbled with them. . . Disturbing the water produced clouds of flickering blue-green plankton, an effect one follower compared to the Milky Way. Sometimes they entered the water and bathed in the phosphorescence, carrying it out on their skin. The Allure of Immortality interweaves the stories of Teed, his followers, the press, turn of the century society, and the harsh and beautiful landscape of southwest Florida. I couldn't recommend it more highly—as high as the heavens above, or even beyond them to China.

James Barrett-Morison, a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor, is a native Miamian now living in Boston, Massachusetts. Finding the Fountain of Youth: Ponce de Leon and Florida's Magical Waters by Rick Kilby

(University Press of Florida, Paperback, 136 pp., $14.95) Reviewed by Marci Calabretta "Every kid growing up in Florida learns that the Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon led the first bunch of Europeans to land on the peninsula, on April 2, 1513. And for decades, they were also taught that Ponce was on a special quest . . . a magic fountain that restored youth." Whether you are a Florida native or have only visited, you have probably heard of Ponce's quest, and may have even dipped your toes into some Floridian water at least once or twice. Although the Sunshine State's springs hold no magical properties, "the story of the mythical, magical waters is in so many ways the story of Florida." Rick Kilby, a graphic designer in Orlando, Florida, stumbled upon his own quest for the Fountain of Youth during a family gathering in St. Augustine, which is reputed to be Ponce de Leon's landing site. While exploring a spring's tourist attractions, Kilby found it to be "both kitschy and historic, and I loved it." Soon after he began traveling up and down the state, hitting every tourist spot that even remotely connected itself to the great Spanish explorer and his legendary spring. Finding the Fountain of Youth is a compilation of Kilby's findings, from historical facts about the state's development to vintage brochures, postcards, and archival photographs of the various "tourist traps." This colorful book begins with a brief history of Ponce de Leon's exploits: how he mistook Florida for another island, began his search for gold, and attempted to establish colonies among the indigenous Native American settlements. Kilby debunks a few myths, and then describes how local advertisements appropriated the Spaniard's quest for the Fountain of Youth to boost the tourist trade. After the Civil War, and again in WWII, waves of veterans and the elderly settled roots into the swamps of the state, making their way inward from the coast. Even Harriett Beecher Stowe, in a chapter of her 1872 book Palmetto Leaves entitled "Florida for Invalids," said, "If persons suffer constitutionally from cold; if they are bright and well only in hot weather; if the winter chills and benumbs them, till, in the spring, they are in the condition of a frost-bitten hot-house plant—alive, to be sure, but with every leaf gone—then these persons may be quite sure they will be better for a winter in Florida, and better still if they can take up their abode there." Thus, the myth was perpetuated that Florida's springs held magical anti-aging properties. Not only were the sick and aged drawn south, but also the wealthy and successful, including railroad tycoons Henry Plant and Henry Flagler. Their railroads settled parts of Florida previously untouched. Over 700 springs were discovered, "the largest concentration of springs on the planet," according to journalist Cynthia Barnett. Floridian architecture blended "Moorish, Spanish Colonial, Mission, and Italianate" to create a so-called " fantasy Mediterranean Revival" that can still be seen today: "Cream stucco. Scarlet hibiscus. Black iron grilles. High above, the whispering fronds of a coconut palm. A great red jar in the corner. A table set for luncheon on the cool, tiled floor. A brilliant splotch of sun on the wall. Your Spanish garden? Why not?..." Kilby uncovers for us a Florida that goes beyond its beaches and palm trees. Packed with mermaids, ancient springs, strange stone crosses, springs, and lions, Finding the Fountain of Youth is perfect for anyone who has not explored the "tourist traps" and is interested in both the history and mythic attractions of the Sunshine State. Every page is filled with fun facts, vintage flavor, and colorful photographs of the state boasting "perpetual rejuvenation." Whether or not you call Florida your home, you will find something magical about the waters rippling through these pages. Marci Calabretta grew up in Ithaca, NY and is currently earning an MFA at FIU. Her chapbook, Last Train to the Midnight Market, is out from Finishing Line Press. She is the co-founder and managing editor of Print Oriented Bastards and a Contributing Editor at The Florida Book Review. |