FBR Feature: Stephen Crane

Expeditions and Affairs: Stephen Crane's Journey to Becoming a Florida Writer

By Dariel Suarez

By Dariel Suarez

Early Years

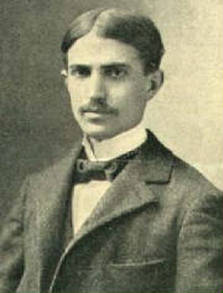

How did Stephen Crane, born in New Jersey into a minister's family, the youngest of fourteen children, become the audacious, notorious writer who "married" the owner of a Florida bordello and nearly died attempting to reach Cuba to report on the Spanish American War?

How did Stephen Crane, born in New Jersey into a minister's family, the youngest of fourteen children, become the audacious, notorious writer who "married" the owner of a Florida bordello and nearly died attempting to reach Cuba to report on the Spanish American War?

|

Born November 1st, 1871, Crane possessed, from an early age, a sense of adventure that led to a near-drowning as he paddled unsupervised in the Raritan River when he was four and a peculiar obsession with colors that made him follow the red skirt of a young lady who was visiting his family. Entranced, young Crane trailed the girl from his home to the nearest street corner, an event curiously characteristic of his adulthood.

After the death of his father in 1880, Crane went through a religious seminary, attempted to obtain an engineering degree at Lafayette, and transferred to Syracuse University's College of Liberal Arts. There he decided to leave university life for good and become a full-time writer. In 1892, he moved to New York, where he worked diligently on his craft, producing within three years Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, The Red Badge of Courage, and his first collection of poems, The Black Riders and Other Lines. Crane received critical praise for his fiction, cementing himself as a popular figure, especially after The Red Badge of Courage became a nation-wide bestseller. Scandal in New York In September of 1896, Crane, then working for the New York Journal, was researching a story about "the life of the metropolitan policeman" when he scheduled an appointment with a couple of chorus girls at the Turkish Smoking Parlors to study what he called "victims of injustice." |

As he accompanied the two women from the Parlors to the Broadway Garden, a disreputable establishment, another woman, Dora Clark, joined the group. Crane was unaware that she was a streetwalker who had been detailed on several occasions. After ushering one of the chorus girls onto a cable car, Crane noticed that Dora and the other chorus girl were being arrested for soliciting. The chorus girl claimed that they had done nothing wrong and that Crane was her husband, and Crane played along. The police officer, Charles Becker, responded by placing Dora Clark under arrest and taking her to the station.

Despite warning by members of the police force, Crane decided to testify on behalf of Dora, a known prostitute. Thanks to his reliable testimony, she was exonerated and released.

Despite warning by members of the police force, Crane decided to testify on behalf of Dora, a known prostitute. Thanks to his reliable testimony, she was exonerated and released.

|

Dora Clark then filed charges against Becker for false arrest. Crane testified at this trial, going against advice given to him by Theodore Roosevelt, then NYC Police Commissioner and an admirer of Crane's work. The Journal described Crane as being "perfectly controlled" and "cold as ice" as he was ruthlessly questioned about his less-than-reputable acquaintances, a clear attempt to undermine his credibility. Though Crane seemed unfazed, his reputation suffered greatly, prompting him to leave New York City, where he could no longer walk freely without being harassed by the police.

Florida Arrival and Cora Taylor Crane left New York in November 1896. Florida-bound, he was given $700 in gold by Irving Bacheller, founder of the first newspaper syndicate in the country. Crane was to work as a war correspondent in Cuba, where rebel forces were fighting the colonial tyranny of Spain. As soon as he arrived in Jacksonville, according to reporter Charles Michelson, Crane began "haunting the backrooms of waterfront saloons, chainsmoking and Drinking countless bottles of beer." Crane wasn't very fond of the town, describing it as "soiled pasteboard that some lunatic babies [had] been playing with." A few days after his arrival, while staying at the St. James, Jacksonville's best hotel, and waiting for a filibustering ship to take him to Cuba, he visited Hotel de Dream, a popular and stylish bordello owned by Cora Taylor. Crane was enthralled by his hostess, discussing literature with her at length, and giving her a copy of his novel George's Mother, inscribed, "To an unnamed sweetheart." Cora, for her part, was familiar with Crane's writings and immediately showed interest in him. She claimed she wanted to be a writer, and saw him as a sort of savior who could remove her from the lewd house of joy. Crane began spending more time at Cora's than at the St. James. Though there aren't many reliable accounts of their relationship at this time, it is clear that Crane and Cora spent a lot of nights together drinking and socializing, possibly discussing literature and writing. |

|

Their fervent connection, however, was cut short, as Crane prepared to leave for Cuba on the SS Commodore on New Year's Eve, 1896.

Disaster at Sea Crane's voyage was the vessel's fifth attempt to reach the island. The ship was carrying over twenty-five men, as well as considerable ammunition to be distributed among rebels in Cuba. As they made their way down the St. John's River, a heavy fog impaired the pilot's vision, causing him to collide with a sandbar. The Commodore was towed off the sandbar the following day and continued its trek without the captain or crew properly examining the ship's damaged hull. Soon a leak began in the boiler room. The crew was unable to repair the malfunctioning water pumps. The Commodore came to a standstill miles away from the closest shore. The Cuban members of the group were lowered in the first two boats. Witnesses described Crane's behavior as poised and admirable, that of a true sailor, while the rest of the crew abandoned the sinking ship in the early hours of January 2nd. Stephen Crane, Captain Edward Murphy, oiler William Higgins, and Steward Montgomery were the last to leave the ship. They got into a ten-foot dinghy, the smallest lifeboat. |

|

Looking back, the men in the dinghy saw a group still aboard the ship, then in danger of submerging at any moment. Mate Frank Grain, wanting to retrieve a forgotten article, had ordered his lifeboat back, putting the lives of seven men at risk. Some of them made rafts and pleaded with Captain Murphy to tow them, since they could no longer return to their lifeboat. The men in the dinghy tried to help, to no avail. The sea was too rough. Mate Grain, who had stayed on the Commodore, plunged into the sea to certain death. The lifeboats and rafts scattered. Crane and three other men were now in charge of their own survival.

Using the Mosquito Inlet lighthouse as a reference point, the men in the dinghy rowed toward shore. By late afternoon, they found themselves close to land near Daytona, huge breakers between them and safety. The captain fired his gun and waved a flag of distress when he noticed people on the beach. From such a distance, however, the people on shore thought the men were fishing. They left without getting help. A near-disastrous effort to fight through the waves convinced Crane and the others to spend the night at sea. On the morning of January 3rd, certain that no one would rescue them, they decided to risk it all. As they feared, the strong surf overturned the small boat, forcing the men to swim toward shore. To avoid being weighed down, Crane released his belt that held the $700 in gold. At one point Captain Murphy had to keep Crane from going under after Crane began to suffer from cramps. By the time they reached shore, where a man named John Kitchell assisted them, Crane, Captain Murphy, and Steward Montgomery were barely alive. Oiler Higgins hadn't been so lucky. He had drowned, his dead body lying face down on the sand. Women from the town brought the survivors coffee, remedies, and blankets. Crane had survived the ordeal that would inspire his classic short story "The Open Boat." |

The Commodore Controversy

Soon after the sinking, some suspicion arose. Reporters wondered whether sabotage or careless overloading had caused the disaster. Captain Murphy stated in an interview that neglect had doomed the ship. Crane indicated that the vessel appeared to be in great condition and that the leak in the boiler room was a strange occurrence. In the end, nothing proved foul play. Other questions were raised about Murphy. Maritime codes say a captain is supposed to be the last person to abandon ship. Grain seemed to have reproached the captain for not returning to help, but Murphy's arm had been broken by a crashing wave before he left the ship, so according to witnesses it would have been pointless for him to struggle back onto the Commodore. |

|

"The Open Boat"

Upon hearing about the disaster, Cora telegraphed Crane, asking him to return to Jacksonville. Since it was Sunday and no locomotives were running, she offered to pay for a private one. Crane refused. Unable to wait, Cora chose to go get him. A witness recalled that when they met at the Daytona train station they kissed "like lovebirds." A few weeks later, in mid-February of 1897, Crane wrote most of "The Open Boat" while at the St. James and the Hotel de Dream or sitting in waterfront cafes. He read the first draft to Captain Murphy, who stated, "That is just how it happened, and how we felt." Crane's relationship with Cora blossomed during this time. When Crane decided in March to go cover the Greco-Turkish war, Cora wanted to go, expressing her need to be with him at any cost. Crane left for New York to make arrangements with the New York Journal, while Cora stayed in Jacksonville to sell the Hotel de Dream. Life After Florida The Greco-Turkish conflict lasted only thirty days. The loving couple, done reporting from the war, settled in England, where Crane introduced Cora as his wife and she took his last name, though she was legally unable to marry. Her previous husband, Donald William Stewart, had refused to divorce her. |

|

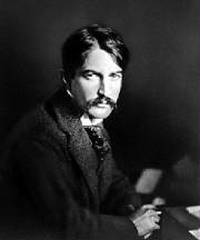

For the rest of the year, Crane wrote a number of short stories and articles that unfortunately did not translate into much income. He became friends with notable writers such as Joseph Conrad (a big admirer of Crane's style), H.G. Wells, and Henry James, all of whom remained close friends until Crane's death.

Despite their moderate income, Crane and Cora enjoyed giving the impression of affluence. They were not shy about spending money and mingling with the elite. They rented a villa in Ravensbrook, though they could not afford their expenses. Anxious to witness a war, Crane jumped at the opportunity to report from Cuba. He arrived in Key West in April 1898, two days after Spain declared war against the U.S., marking the beginning of the Spanish-American War. Crane spent time in Key West and Tampa acquiring information before landing in Guantanamo Bay in June. Communication with Cora was difficult, and she would go weeks at a time without hearing from him. Meanwhile Crane's tuberculosis, which he'd contracted at an early age, quickly worsened. Last Days Crane reunited with Cora in England in January of 1899. The couple moved to Brede Manor, an infamous estate said to be haunted by the spirits of children. Crane spent the majority of the year writing and battling his illness. In December, Crane and Cora put together a lavish party that was to last several days. Conrad, Wells, and James attended, joining the couple in raiding the pantry, playing games, and enjoying music. On December 29th, while Crane played the guitar, he collapsed onto the shoulder of a guest, spitting blood. His condition deteriorated and in April of 1900 he suffered two more hemorrhages. He wrote his will at the end of the month, leaving all his personal possessions to Cora. In a futile attempt to help him, Cora took him to a spa in Germany, but on June 5th, 1900, Stephen Crane passed away in his bed at the age of 28. |

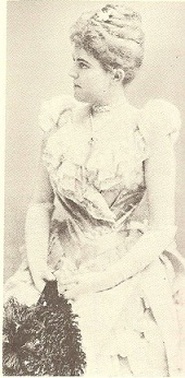

Cora Crane

Born in 1865, Cora Taylor married twice before she met and fell in love with Stephen Crane. She became the first female war correspondent when she reported from the Greco Turkish War under the pen name Imogene Carter. After Crane's burial, she returned to England in the summer of 1900. She struggled to keep a steady income, accepting money from influential friends and battling with creditors, until she left the country in 1901. She spent a few months in New York, Kentucky and New Orleans before settling in Jacksonville in 1902. There she built another brothel, the Court, which she managed. She married Hammond McNeil in 1905, and two years later he shot and killed one of her lovers. Cora refused to testify in McNeil's trial, he was acquitted, and the couple divorced. She managed the Court until 1910, when she suffered a stroke and passed the managing duties to her housekeeper. Cora died in September of the same year, collapsing from heat exhaustion after helping to push a car out of the sand. |

|

Legacy

Obituaries compared Crane to Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Louis Stevenson. Cora brought his remains back to the United States, and his funeral was held in New York. Among the attendees was Wallace Stevens, then twenty-one. Stephen Crane was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Hillside, New Jersey. Crane's time, in Florida and in the world, was brief but memorable. From his affair with Cora and the Commodore ordeal to crafting "The Open Boat," Crane's footprint in Florida must be recognized. Today he is considered a Florida writer, and his literary landmark is located in Daytona Beach at Lilian House (today the oldest home on the beach side of Daytona Beach), where he stayed after the shipwreck. Dariel Suarez was born in Havana, Cuba, where he lived until 1997. He resides in Miami with his wonderful wife and a large number of books. Dariel's fiction and poetry have appeared in several publications including Skive, elimae, Vain, and The Absent Willow Review, where he received an Editor's Choice Award.

|

More info on Stephen Crane may be found here:

— The Stephen Crane Society

— The Stephen Crane House

— The Heritage Preservation Trust of Volusia County has begun fundraising to restore the Lilian Place House, site of the Stephen Crane Florida Literary Landmark.

— The Stephen Crane Society

— The Stephen Crane House

— The Heritage Preservation Trust of Volusia County has begun fundraising to restore the Lilian Place House, site of the Stephen Crane Florida Literary Landmark.