Florida Music, Arts, & Architecture

On this page:

◇ Florida Soul: From Ray Charles to KC and the Sunshine Band by John Capouya, reviewed by Robert Morison

◇ Music Everywhere: The Rock and Roll Roots of a Southern Town by Marty Jourard, reviewed by Daniel Santos

◇ Enchantments: Julian Dimock's Photographs of Southwest Florida, edited by Jerald T. Milanich and Nina J. Root, reviewed by Pamela Akins

◇ Great Houses of Florida by Beth Dunlop, Joanna Lombard, and Steven Brooke, reviewed by Molly McGreevey

◇ Jazz From Row Six, Photographs 1981-2007 by Jean Germain, reviewed by Louis K. Lowy

◇ The New Deal in South Florida: Design, Policy, and Community Building 1933-1940, edited by John A. Stuart and John F. Stack, Jr., reviewed by Antolin Garcia Carbonell

◇ Key West in Black and White by Tom Corcoran, reviewed by Harry Calhoun

◇ A Florida Fiddler: The Life and Times of Richard Seaman by Gregory Hansen, reviewed by Leejay Kline

◇ Fiddler’s Curse: The Untold Story of Ervin T. Rouse, Chubby Wise, Johnny Cash and The Orange Blossom Special by Randy Noles, reviewed by Mark M. Martin

◇ Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida by Bobby Braddock, reviewed by Gene Hull

◇ Florida Soul: From Ray Charles to KC and the Sunshine Band by John Capouya, reviewed by Robert Morison

◇ Music Everywhere: The Rock and Roll Roots of a Southern Town by Marty Jourard, reviewed by Daniel Santos

◇ Enchantments: Julian Dimock's Photographs of Southwest Florida, edited by Jerald T. Milanich and Nina J. Root, reviewed by Pamela Akins

◇ Great Houses of Florida by Beth Dunlop, Joanna Lombard, and Steven Brooke, reviewed by Molly McGreevey

◇ Jazz From Row Six, Photographs 1981-2007 by Jean Germain, reviewed by Louis K. Lowy

◇ The New Deal in South Florida: Design, Policy, and Community Building 1933-1940, edited by John A. Stuart and John F. Stack, Jr., reviewed by Antolin Garcia Carbonell

◇ Key West in Black and White by Tom Corcoran, reviewed by Harry Calhoun

◇ A Florida Fiddler: The Life and Times of Richard Seaman by Gregory Hansen, reviewed by Leejay Kline

◇ Fiddler’s Curse: The Untold Story of Ervin T. Rouse, Chubby Wise, Johnny Cash and The Orange Blossom Special by Randy Noles, reviewed by Mark M. Martin

◇ Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida by Bobby Braddock, reviewed by Gene Hull

|

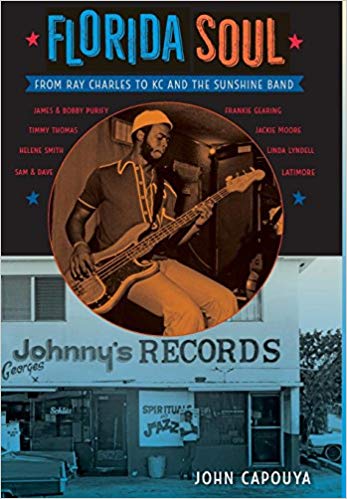

Florida Soul: From Ray Charles to KC and the Sunshine Band by John Capouya

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 396 pp., $24.95) Reviewed by Robert Morison Note: Florida Soul has received the Florida Historical Society's 2018 Charlton Tebeau Award. |

Florida Soul: From Ray Charles to KC and the Sunshine Band by John Capouya

Reviewed by Robert Morison John Capouya's Florida Soul is a book on a mission to demonstrate that “Florida’s contributions—to soul, rhythm and blues, funk, and 1970s dance-soul or disco—are equally rich, and deep” as those of Memphis, Detroit, New Orleans, and Philadelphia. Evidence comes in the form of profiles of singers, musicians, and producers with Florida roots and presence. Ray Charles was born in Georgia but came to Florida as an infant, and he learned to navigate as a musician and a blind man in the clubs and on the streets of Jacksonville, Orlando, and Tampa. Quintessential “Soul Man” Sam Moore of Sam and Dave grew up in the Overtown section of Miami. James and Bobby Purify (not related—Bobby’s name was Ben Moore) hailed from Pensacola. Their “I’m Your Puppet” wasn’t soul but was a big and often-covered hit. Miami’s Timmy Thomas sang his “Why Can’t We Live Together” at Nelson Mandela’s inaugural celebration. The beat goes on. Featured female vocalists include Miami’s Helene Smith (“Willing and Able”) and Betty Wright (“Clean Up Woman”) and Jacksonville’s Jackie Moore (“Precious, Precious”). Two white soul singers rate profiles: Gainesville’s Linda Lyndell (“What a Man”), who sometimes sported an afro wig in lieu of her 60s bouffant, and Miami’s Wayne Cochran, “the white James Brown,” who made it onto The Jackie Gleason Show. Capouya gives due respect and coverage to the musicians, both headliners and studio band members. There are profiles of legendary saxophonists Ernie Calhoun and Noble “Thin Man” Watts, from Tampa and Deland, respectively. The T.K. Productions crew, including Little Beaver on guitar, Chocolate Perry on bass, and Timmy Thomas or Latimore on keyboard, gets an ensemble chapter. And praise goes to the master “sweetener,” Mike Lewis, who added string and horn tracks to make the bands bigger. On the R&B and Soul circuits, everybody crossed paths with everybody else. In South Florida, paths most often crossed at the studios of T.K. Productions in Miami and under the auspices of producer, distributor, record-label owner, and self-proclaimed “payola king” (radio DJs would play a record for a modest remuneration) Henry Stone. He produced Ray Charles, the Sunshine Band, and many of the book’s other featured artists in between. Wheeler-dealer he was, modest he was not. He told Capouya, “I am the story of Florida soul, so your book is really all about me. . . . So, I’m thinking, I should get a cut.” Music trends are part of the story. The provenance of the twist craze is disputed, but Hank Ballard’s original version was first played in Tampa and then recorded in Miami (for Henry Stone, of course). The Caribbean-inspired “Miami Sound” took shape on T.K. recordings in the early 70s before reaching wide popularity with KC and the Sunshine Band and the Estefans’ Miami Sound Machine. Venues also tell a story. Capouya describes the vibrant music scenes of the 50s through 70s in Jacksonville juke joints, “Tampa’s Harlem” along Central Avenue, and especially Miami’s Overtown. In the segregation era, the biggest names—Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington, Billy Eckstein—performed on Miami Beach but weren’t allowed to lodge there. So they stayed in Overtown, frequented its clubs (where whites were welcome), and sometimes joined in wee-hours jam sessions. The entertainment districts in Jacksonville and Tampa suffered slow declines. Overtown’s was sudden when the neighborhood was targeted by politicians and divided by the construction of Interstate 95. The subjects of Florida Soul have much in common. Many of the singers began in gospel choirs but then fell under the secular influences of R&B and early rock ’n roll. They went on the road while in their teens, exposed to its vices and feeling the burden of the region’s racism. Many persevered through what they saw as the scourge of disco, and most are not fans of hip-hop and rap. Several still perform occasionally. Quite a few, including extraordinary instrumentalists, did not read music but could play or sing by ear and innovate at will. Always-in-demand Chocolate Perry (who toured with the Bee Gees and played on recordings by Dolly Parton, Kenny Rogers, Dionne Warwick, and Gloria Estefan) explained, “When you are trained that ‘This only goes this way,’ you’re limited in your perspective. I would put things together that were not supposed to go together. . . . My not knowing all the notes opened my mind up to any possibility.” Capouya profiles the music as well as the performers. He describes theory and technique (it helps to understand chord structure), quotes the lyrics, and adds his appreciation. Of Latimore’s “Let’s Straighten It Out,” he writes: “It’s masterfully sung, showcasing the power and soulful timbre of Latimore’s voice. He attacks the lyric with intensity from the first line, and the abrupt transition from the more reflective instrumental intro into his vocals only emphasizes their fervor, which never lets up Florida Soul is the product of a vast amount of research. Capouya, who teaches journalism and writing at the University of Tampa, interviewed almost all of the principals who were still around and quotes them regularly. So he narrates, but they tell their stories, giving the book a “you were there” feel. There are photos throughout of 45s, venues, posters, performances, and performers—publicity shots from back in the day and charming post-interview photos of them today. Capouya indicates how to access some original recordings and filmed performances on YouTube, and he can quote the prices of the original vinyl on eBay.

The chapters can be read in any order. Capouya cross-references, draws connections, and repeats details where they apply to multiple profiles (as mentioned, paths cross a lot). A thorough index and selective bibliography await those who want to learn more. So does Florida rank up there with the meccas of R&B and soul? That remains entertainingly debatable. But Florida Soul does put the Sunshine State definitively on the map. And it’s a book for Soul Survivors everywhere. Bob Morison is co-author of Workforce Crisis and Analytics at Work. He lives in Miami. More info at his website. |

|

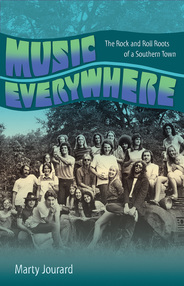

Music Everywhere: The Rock and Roll Roots of a Southern Town by Marty Jourard

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 261 pp., $19.95) Reviewed by Daniel Santos |

Music Everywhere: The Rock and Roll Roots of a Southern Town

Reviewed by Daniel Santos Music Everywhere: The Rock and Roll Roots of a Southern Town is about how Gainesville, Florida sprouted a plethora of talented musicians in the rock scene in the 1960s and 70s, from Steven Sills and Tom Petty to Eagles founding member Bernie Leadon and many more. One of the best things about the book is that it’s written by one of those musicians. Marty Jourard, a native of Gainesville, knows a thing or two about rock and roll. He played alongside Martha Davis in The Motels for decades. Along with his band he won numerous awards including two Australian Gold Records for the hit song “Total Control.” While Marty Jourard is a successful musician, he speaks little of himself in the book. His focus is the Gainesville music scene. However, Jourard doesn’t just jump into the music right off the bat. Jourard believes that a large part of why so many successful artists came out of Gainesville is the town itself, and he describes it with the utmost beauty and nostalgia: In the years that preceded the sudden growth in its live music scene, Gainesville was more conservative and relatively idyllic . . . In the summer the county health department dispatched a flatbed truck that slowly drove through neighborhoods in the evening, spraying a white mist of vaporized kerosene to control the mosquito population; kids would gleefully run through the fog and follow the truck down the street. After school, children would play outside until dark. In certain neighborhoods each mother had a handbell she would shake to signal when it was dinnertime; you knew the sound of your bell. Children often ran around barefoot. Some older kids would go frog-gigging at night and return home with a bucket of bullfrogs. Rattlesnake Creek ran through part of the city, and younger kids, including this writer, would wade through the shallow water and routinely find and collect ten-million-year-old shark teeth and fossilized shells. Deep pools in the creek held crayfish, water snakes, minnows, and softshell and snapping turtles. Dragonflies hovered about, and the unique sound of cicadas filled the air as you waded about: you were a part of the nature that surrounded you. Gainesville and nature were inseparable. Gainesville was a uniquely beautiful place. It was a small town with a state university that was growing in the post-war era. It was a southern town but it was also a place where a multitude of different cultures and people gathered. For instance, Jourard touches on Tom Petty’s grandfather, William ‘Pulpwood’ Petty. William, who lived in Waycross, Georgia, had married a full-blooded Cherokee woman. As a result, he wasn’t welcome in Georgia, so he crossed the border into Florida and settled in Gainesville.

While Jourard often journeys into the past of the musicians in Music Everywhere, his basic structure is chronological. There is no full chapter on prominent musicians like Tom Petty or Stephen Stills. Instead, each chapter corresponds to a particular year and is filled with multiple stories of bands and what they were doing at the time. This shows their growth as musicians. One particular story about Don Felder, a boy who would go on to become the lead guitarist of the Eagles, comes to mind—the night "around 1960 or 61" when he met B.B. King. Felder and a friend, who stole his father’s Jeep, went outside the city limits to see the legend play. As Felder recounts, Blacks would play outside city limits and in barns because liquor licenses weren’t issued to clubs in what were called Colored Towns. “Neither Don nor his friend had the five-dollar admission charge, so they listened and watched the performer from a window. In Felder’s words, ‘I saw women crying and screaming “Tell it like it is, B.B.!” and him standing there with his Gibson 335 or whatever it was he was playing, plugged into a Fender Concert set on 10. Every knob was on 10 because I saw it when I walked up to the stage afterwards. And he played four sets, and between each set he’d walk back and sit in the back, which was the horse stall, with bales of hay in it. It was in a real barn. I have no idea where it was; we had to ride in this guy’s Jeep through cow pastures to get there. So I walked in the back door, and there was B. B., and I introduced myself and told him I’d bought this record, and I loved his playing, and he was so nice and kind.’” Jourard doesn’t just trace the history of these artists, he also shows the effect music had on the town itself. One such story involves Buster Lipham, an owner of a small instrument store that blew up after the Beatles hit it big on The Ed Sullivan Show. All the local bands hung out there. Tom Petty even worked there back in ’67. However, my favorite thing about Music Everywhere is the music. At the start of each chapter—with the exception of the first and last ones—Jourard provides a full playlist of the top songs of the corresponding year as well as particular songs of bands that will be covered in the chapter. I loved this feature. It provided me a platform to get familiar with the music of the day, as well as helped beef up my own personal playlist on Spotify. Having heard the listed songs, I was able to follow exactly what the pros were talking about throughout that chapter—why the Beatles were so revolutionary and how they influenced musical powerhouses like Tom Petty. I felt the bands grow through the years. I heard them change with every new member as well as with the times. The playlists are integral to this book, and I recommend that readers listen before starting a chapter. It may slow down reading, but it’s worth it. The final chapter is titled "1977-Present," and helps to show how the influence of the music that flourished in Gainesville continues. I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in music in general, but especially to those into rock, blues, R&B, country, soul, blue grass, folk, punk, grunge, post grunge, electronic, industrial . . . heck, if you like anything that makes a pretty sound you might like this book. Also, those who are interested in Florida or the South will find this book enjoyable—I certainly did. Born in the not so mystical land of Miami, FL, Daniel Santos is an avid reader and writer of science-fiction and fantasy. He is a graduate of Florida International University. |

|

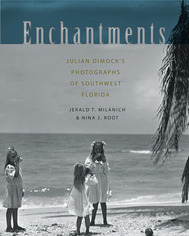

Enchantments: Julian Dimock's Photographs of Southwest Florida edited by Jerald T. Milanich and Nina J. Root

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 172 pp., $34.95) Reviewed by Pamela Akins |

Enchantments: Julian Dimock's Photographs of Southwest Florida

Reviewed by Pamela Akins If a picture is worth a thousand words, what does one say about 100-plus photos from a time and place of bygone beauty and primordial mystery? Enchantments is a new coffee-table book of photographs taken by Julian Dimock and A. W. Dimock, when they sailed and paddled through the waterway wilderness of Southwest Florida and the Everglades during the first decade of the 20th century. Artistically rich and sometimes curiously strange, the images have been pulled from the archives of the American Museum of Natural History by Nina Root, director emerita of the museum’s research library, and Jerald Milanich, curator emeritus of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Julian Dimock and his disgraced financier father were “gentlemen explorers” who published hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles documenting their treks through Florida swamps and savannahs between 1904 and 1913. Using Marco Island as their base, they sailed the ragged Southwest Florida coast in their houseboat, the Irene. With smaller craft, they explored the rivers flowing into the Ten Thousand Islands and canoed into the Everglades and Big Cypress Swamp, amassing almost 2,000 photographic negatives on glass plates. The photos illustrated nearly 80 articles for Collier’s, Field and Stream, Harper’s, Scribner’s, Country Life in America and other periodicals. Enchantments is divided into four segments: “The Coast,” “The Mainland,” “The In-Between,” and “The Last Florida Adventure.” In each segment, the photographs are organized by subject matter. Captions accompanying the images offer excerpts from the original magazine articles written by the Dimocks as well as additional historical information about the individuals, places and wild life featured. The book’s duotone printing in black and gray ink enhances the depth and richness of the images. And the glass plate negatives often create sharp light and dark contrasts: dark palm fronds are splayed against a clear sky, a tangle of black mangrove roots gird a white shore. Some of the most striking photos capture the play of light in this place of abundant sunshine. Diffused sunlight streams from behind storm clouds, bright light reflects off white-sand beaches, and a sun sets on a hard-edged Gulf horizon. One of the most beautiful duotones is the book’s cover photo; it catches the softness of young girls in white pinafores drinking cocoanut milk on a Marco Island beach. Another startling image shows a man hand-fishing from a canoe, a large hooked tarpon twisting mid-air and white spray dotting the space beneath it. This photo was used for the cover of The Book of Tarpon, the Dimocks’ definitive guide to tarpon fishing still in print and a favorite of fishermen today. The amazing thing about these pre-Ansel Adams pictures is that they were taken when this part of Florida was still untamed, beyond the frontier of Anglo civilization, and before development had reduced the images’ placid streams, impenetrable mangrove thickets and enigmatic shell mounds to truck farms, condominiums and gated communities. Photo after photo bears witness to this uneasy Eden and the fierce beauty of its flora and fauna: interminable saw-grass and flower-clogged rivers, massive live oak roots and giant cypress trees, nesting blue herons and young turkey-neck anhingas, trussed alligators and torpid crocodiles. The photos not only document the area’s wild beauty, they also offer a rare glimpse into the hardscrabble lives of the men and women pioneers of this mosquito-infested wilderness. There are Seminoles in straw hats and striped skirts poling the Everglades, Florida crackers with mud-crusted wagons, African Americans picking pineapples, moonshiners tending a still at night, and wary outlaws sitting on porches, vigilant against frontier justice. The images also show the encroachment of civilization: hummocks cleared for grapefruit groves, a warehouse for phosphate mined from the Peace River, heron rookeries threatened by plumage hunters, a corduroy road cut through the swamp to Deep Lake Plantation. Each stark image wraps you into an inscrutable past world, when the wild and dangerous still possessed Southwest Florida, but also when 20th-century “progress” lurked at its edges and the frontier was slowly yielding to man’s transformation. These beautifully luminous, historically enlightening and occasionally transcendent images truly are enchantments worth getting lost in. Pamela Akins is creative director of Akins Marketing and Design, and, although a born and bred Texan, she now lives in Sarasota, FL and New London, CT. |

|

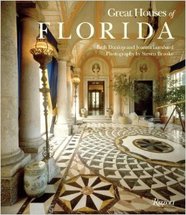

Great Houses of Florida by Beth Dunlop, Joanna Lombard, and Steven Brooke

(Rizzoli, Hardcover, illustrated, 256 pages, $55) Reviewed by Molly McGreevy |

Great Houses of Florida

Reviewed by Molly McGreevy Eighty years ago the New York Times reported that, although Florida’s real estate had been able to make many people “fabulously rich overnight,” by 1927 “hundreds of persons who bought property during the boom…were unwilling to make further payments when the slump came and chose rather to write off their deficits and let the investment drop.” Sound familiar? You don’t need to look at the foreclosure signs across the street or the newly erected but empty condominiums in your downtown area to know the same thing could be written about our housing market today. The Times quote begins the introductory discussion in Great Houses of Florida, an informative photography book showcasing the state of Florida’s most treasured houses. According to authors Beth Dunlop and Joanna Lombard, Florida’s “boom and bust” past, which is destined to keep repeating itself, provides the contemporary visitor with one (of many) lenses through which one can view its historical architecture. In spite of hardscrabble living conditions and plenty of swamp water, dreamers back then—just like they do now—insist on taking a chance in La Florida, the “Land of Flowers.” The book offers an array of Florida homes and styles. Beginning in Key West with the Audubon and Hemingway houses and then traveling north, the book’s handsome photography gives intimate glimpses of well-known attractions such as the Deering’s Vizcaya in Miami and the Ringling’s Ca d’Zan in Sarasota. Readers can also peek into a St Augustine coquina-rock home complete with furnishings c. 1770. Other homesteads, such as those belonging to Marjorie Rawlings, author of The Yearling, and La Casita, a preserved cigar maker’s house in Tampa, are more modest but provide a window on Florida’s past. Continuing west in the Florida Panhandle, one can walk through Historic Pensacola Village, where over twenty homes have been listed. The text gives a detailed explanation of the historical and stylistic influences, if any, on each house. Enthusiasts will be satisfied the authors have done extensive research. Dunlop is editor-in-chief of HOME Miami and HOME Fort Lauderdale magazines and an architecture critic of the Miami Herald, and Lombard is a professor at the University of Miami School of Architecture. And Steven Brooke’s photography is lush and colorful, much like the paradisaical gardens growing around these estates. In fact, the plants here attracted many famous scientists and naturalists, whose houses are included in the book. Charles Deering was one of these. A visit to his 144-acre estate at Cutler reveals a breathtaking view of a shoreline vista, its rows of palms preserved against the advice of his architect. David Fairchild bought his Kampong estate in Coconut Grove and used the grounds to study his collection of rare plants and trees. And in Fort Myers, Thomas Edison erected a winter home that also included a laboratory for his work with rubber plants, his gardens used for both “pleasure and science.” Even then, these botanists were deeply concerned about the rapid development on Florida’s natural resources and urged others to stop the destruction of our mangroves and hammocks. But, as is remarked in the book’s introduction, the “bust” part of the housing cycle is what preserves Florida’s natural wild and plant life. During a time of economic fear, at least we can take comfort in the fact that the downturn will force the slowing of development. It may be what saves some of our dwindling resources. Great Houses of Florida is an excellent coffee table book, but it’s also an interesting read for the architecture or design buff. For those wishing to visit any of these homes, an index lists all addresses and contact information. Molly McGreevy lives in a modest Floridian home in the city of Miami. |

|

Jazz From Row Six, Photographs 1981-2007 by Jean Germain

(New Chapter Publishers, Hardcover, 96 pages, $45) Reviewed by Louis K. Lowy |

Jazz From Row Six, Photographs 1981-2007

Reviewed by Louis K. Lowy Visualize sitting in the sixth row of a concert hall listening to the architects of America’s most revered music performing with the velvety, belly-warming heat of a twenty-year-old Scotch. Savor the joy in the musician’s eyes, the way their fingers ripple from key to key, valve to valve, drum skin to drum skin. Imagine what it was like for them, ages ago, to be standing on an oak plank stage in a smoke waffled speakeasy with Jelly Roll Morton, Louie Armstrong, and Count Basie, creating rhythms and melodies that would influence virtually all music from that moment forward. These pioneers, many no longer with us, were photographed by Jean Germain from 1981 to 2007. Her work fills Jazz From Row Six. Germain, a retired school teacher, moved from New York to Sarasota, Florida in 1979. Shortly afterward at Pelican Cove community tennis courts she had a chance encounter with Hal Davis, big band icon Benny Goodman’s publicist for thirty-five years. Germain and Davis struck up a friendship over their mutual love of jazz. An amateur photographer, Germain was asked to become the official photographer for the Jazz Club of Sarasota’s monthly concerts and the annual festival, both run by Davis. “Not feeling up to the task,” Germain writes, “I told him that I was not the person for the job—I didn’t know an f-stop from a truck stop . . . But Hal could be as persuasive as he was charming . . . And so, with his—and my husband’s—encouragement, I began my second career, and it has certainly changed my life!” Germain took photography classes and attended workshops to improve her skills. She was given the choice of choosing her viewpoint at the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall, where the jazz greats performed. As she put it, “I picked (row six) because I didn’t want to be so close that I would have to shoot everything looking up at an angle, nor so far away that I couldn’t capture the faces of the musicians in close-ups.” While she had an unprecedented access point she also had unique problems. “I was not only handicapped by being confined to one seat. I could not use a tri-pod to steady my camera. Stage lighting was my only illumination, as no flash was allowed.” Germain overcame the lighting obstacles by utilizing fast speed film, slower shutter speeds, and special filters. Most of the photographs are in black and white. The results create an impressionistic feel that evokes an earlier era and adds to the elegant grace of the aging musicians. “I liked the soft, blurry edges. I felt that in many cases they were just right for what jazz was all about.” Beyond the technical aspects, Germain has an eye for the emotional. She presses the shutter at exactly the right moment. It’s striking to view a 1992 photograph of eighty-six-year-old trumpet legend Doc Cheatham, his eyes serenely closed, his trumpet reverently angled toward heaven as if he was heralding his own arrival, which occurred five years later. Germain’s 1992 photo of vibraphone virtuoso Lionel Hampton, eighty-two and having difficulty walking, captures a man overtaken with delight, standing behind his ever present vibes, snapping his fingers like a jitterbug jiving teen to what must have been a rousing chorus of “Sweet Georgia Brown,” or “Hey BaBa Ree Rop.” With each shot Germain captures the essence of the artist: eighty-year-old Hootie McShann—the last of the great pianists who embodied the Kansas City sound—quietly reflecting while his hands smooth over the ivories, octogenarian Eartha Kitt’s playful sexiness as she croons from a chaise lounge, and seventy-two-year-old Latin percussion icon Tito Puente, tongue sticking out, banging his timbales with the glee of a third grader pounding away at a game of Whac-A-Mole. Strikingly, Germain’s collection gives us not only the ecstasy of these musicians when they were performing, but the pleasure she felt snapping these photos. Germain was right when she said this has changed her life. Fortunately for us, in Jazz From Row Six, we get to share that jubilance with her. Louis K. Lowy resides in Miami Lakes. He is the recipient of a State of Florida Individual Artist Fellowship. His work has appeared in Coral Living Magazine, Cartier Street Review, and Merge. His poem "Poetry Workshop (Mary Had A Little Lamb)" was the second place winner of the 2009 Winning Writers Wergle Flomp Humor Poetry Contest. He is currently enrolled in Florida International University's Creative Writing Program. Read more at his website. |

|

The New Deal in South Florida: Design, Policy, and Community Building 1933-1940, edited by John A. Stuart and John F. Stack, Jr.

(University Presses of Florida, Hardcover, 288 pp., $29.95) Reviewed by Antolin Garcia Carbonell |

The New Deal in South Florida: Design, Policy, and Community Building 1933-1940

Reviewed by Antolin Garcia Carbonell Recently awarded the Florida Book Awards Silver Medal for Florida Nonfiction, the six, well researched and unexpectedly timely essays in this beautifully illustrated book revisit how specific New Deal projects and initiatives addressed the social and economic difficulties confronting South Florida’s needs during the Great Depression. The New Deal in South Florida by John F. Stack, Jr. and John A. Stuart describes the big picture economic and social issues the New Deal initiatives faced in Florida and how administrators maneuvered around the Deep South’s distrust of the Federal government and congenital racism. Many of these efforts broke new ground in social relations that later paved the way for the much needed changes brought about by the civil rights movement. “Constructing Identity: Building and Place in New Deal South Florida” by John A. Stuart traces the Federal government’s contribution to the creation of a distinct South Florida architecture through the buildings created under its auspices. These spare, even austere, buildings meant to leave no doubt that money had not been wasted on frivolous decorative elements were in accord with developing modernist architectural ideas and while not meant to be cutting edge design, still managed to convey an image of an elegant, yet efficient and up to date city. “Migrants, Millionaires, and Tourists: Marion Post Wolcott’s Photographs of a Changing Miami and South Florida” by Mary N. Woods takes a look at the South Florida society recorded in the photographs taken under the auspices of the Farm Security Administration. Images of struggling urban workers and destitute farm laborers alternated with those of sleek Art-Deco hotels and the idle rich at play by the sea. Yet, in documenting the contradiction, the F.S.A. also documented part of the solution to the problems of the poor, since ultimately the renascent tourist and construction industries provided one of the means for many of the destitute to a better life. “Whose History Is It Anyway? New Deal Post Office Murals in South Florida” by Marianne Lamonaca analyzes one of the most beloved and long-lasting legacies of the New Deal, the historical murals that grace the lobbies of our Art-Deco Post offices. Intended to complement the spare architecture of the period, the subject matter of these murals reflect the mindset and priorities of the era’s decision makers as well as their biases and conceptions of social and racial hierarchies. “The Civilian Conservation Corps in South Florida” by Ted Baker documents how a program driven by the need to provide employment for young unemployed men built some of South Florida’s greatest parks, among them Greynolds and Matheson Hammock, while “improving” the natural landscape. This legacy of the WPA paid off during South Florida’s post-war expansion and remains a key component of our recreational infrastructure. “Liberty Square: Florida’s First Public Housing Project” by John A. Stuart explores the many contradictory issues that resulted in the creation of this architectural landmark: providing improved housing for the poor while using racist justifications to increase the physical segregation of the Black community. This project also broke new ground in social as well as physical engineering. Tenants were selected to ensure that they were responsible individuals and management provided social support for struggling families. The units themselves came with indoor plumbing, electricity and running water, basic amenities not always available in the rental shotgun houses of Overtown. This timely essay gives a much-needed boost to on-going community efforts to revitalize this once ideal neighborhood that became mired in crime, drugs and social problems. As, once again, South Florida finds itself the recipient of Federal largess to stimulate a moribund economy, The New Deal in South Florida arrives just in time to serve as an invaluable guide for evaluating our options by showing us what worked in the past. A forty-seven year resident of North East Miami, Antolín García Carbonell, a registered architect with professional degrees from the University of Florida and the University of Miami, spent 30 years managing design and construction projects for the Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Read his FBR piece In Search of Florida’s Forgotten Poet Laureate, Vivian Laramore Rader. |

|

Key West in Black and White by Tom Corcoran

(The Ketch and Yawl Press, Paperback, 189 pages, $19.95) Reviewed by Harry Calhoun |

Key West in Black and White

Reviewed by Harry Calhoun Tom Corcoran has produced a lovingly done book of black-and-white photos, one that truly captures the Key West that I know and love. What makes this more impressive is that a lot of Key West’s charm is in its colors: pink bougainvillea, multicolored verbena and lantana, the pink and white houses and orange terra cotta roofs. But Corcoran’s monochrome shots capture the quirky spirit and the beauty of the island. Aside from providing great shots of buildings, the water, Corcoran also gives us short, well-written commentaries on each photo. Almost every one is a gem in its own right. Some of them, like the shot of Elgin Lane on page 39, send chills down my spine with memory of my days there. Corcoran describes the lane as “The essential quiet of the Old Island, a few blocks off the tourist track.” And indeed, I remember riding my bike with friends down lanes like this, off to hear a poetry reading or to have a few beers in the evenings. Corcoran’s photo is so perfect I can almost smell the night-blooming jasmine. The photos vary in mood and spirit. A shot of three shrimp boats with a squall outside the reef behind them is brooding and eerie. So is the photo of what remains of the old Seven Mile Bridge jutting out into the water like an unfinished sentence. Others are more whimsical and fun, bright photos that captures the nearly constant sunniness of the island. He even manages to find an interesting and unusual angle for a photo of the Southernmost House, surely the most overly photographed building in Key West. There are surprisingly few people shots in Key West in Black and White. Corcoran works his magic mostly by letting the island tell its own tale of ramshackle, rundown seediness in the midst of great natural and architectural beauty. The shots were taken from the 1970s through the nineties and are in no chronological order. I also liked the whimsical introduction by Randy Wayne White, who displays some conch pride while introducing us to Corcoran. He ends his introduction by saying, “Welcome to Tom Corcoran’s Key West — the real Key West.” Having lived there, and having fallen permanently in love with the little island, I would have to agree. Tom Corcoran can imbue photos of drugstores, restaurants and fishing boats with a sense of romance and the idyllic beauty of Key West. Harry Calhoun is a widely-published writer of articles, literary essays, and poems. He has recent publications in Chiron Review and poetry forthcoming in Abbey, Word Catalyst and LiteraryMary, and writes a wine column, Ten Dollar Tastings. |

|

A Florida Fiddler: The Life and Times of Richard Seaman by Gregory Hansen

(University of Alabama Press, Hardcover, 254 pp., $45.00) Reviewed by Leejay Kline |

A Florida Fiddler: The Life and Times of Richard Seaman

Reviewed by Leejay Kline In the mid 1950s, after performing across north Florida for three decades, old time fiddler Richard Seaman put his fiddle up. Keith (Richard’s son) was the last guitar player I had, and when he died, why I didn’t have anybody to play with. The fiddle sat right up there on that mantelpiece for thirty years, and I didn’t have any feelings for it at all. Additionally, the young crowds who had always come to dance to Richard Seaman’s traditional songs were discovering a newer music more to their liking. The Rock‘n Roll revolution was in full swing with Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, the Everly Brothers and other southerners leading the vanguard. When he was in his early eighties, Richard began to perform in public again. This time he played in schools, at folk music festivals and folk life symposia. In his absence, old time fiddling had gained a new audience hungry for authenticity. Although not as well known as fellow fiddlers Chubby Wise, Vassar Clements and Erwin T. Rouse, Richard Seaman’s performances, peppered with anecdotes and jokes about the old days in Florida, charmed fans of old-time music wherever he played. He was born in 1904 on a central Florida farm in deeply rural, turn-of-the-century Kissimmee Park, before radio, before movies, before electricity came to that part of the state. Aside from church socials, the common entertainment in Richard’s early years was house parties where families rode in on wagons or walked from miles around to hear a fiddler play for square dances. The men rolled up the rugs and carried the furniture out to the side yard and the mothers put the babies in one room to sleep until the party broke up either from exhaustion or a fight. Richard Seaman picked up his first fiddle when he was 12 and performed at house parties until he moved to Jacksonville in 1926, where he worked as a machinist for the Seaboard railroad until his retirement. In his introduction to A Florida Fiddler: The Life and Times of Richard Seaman, Gregory Hansen lets us know that his book is neither a biography nor an ethnomusicological analysis of Florida fiddling, but rather, a look into the way one man considered his life experiences in relation to his music. We are fortunate that Hansen, who loves and plays traditional music, was lucky enough to cross paths with Richard Seaman. Over the years, Seaman played fiddle with Jimmy Rodgers, Clyde Kirkland, Vassar Clements, Chubby Wise, and Erwin T. Rouse as well as led his own band, the South Land Trail Riders. He was blessed with a good memory of his times and life and had humorous stories and tall tales to fit any reminiscence. When the author lets him speak, which is the heart of the book, the result is happy, engaging and thoughtful. Although rewarding, the book is not an easy one—there are more than 50 pages of acknowledgements, preface, introduction, footnotes and bibliography. Nor is it a straight-on chronological tale of a life that spanned and witnessed racial segregation, the fast urbanization of Florida when many abandoned farm life for what seemed a better one in the cities, the technology and communications explosion, and the loss of common rural customs. The author moves us back and forth in time through interviews, music, stories, recollections and anecdotes to capture his subject’s life in and out of music. Great portions of the book seem to be direct transcriptions of interviews and performances. The chapter titled “Workshop” records Richard Seamen, Chubby Wise and George Custer in performance at a folk life workshop in Jacksonville in 1993. Whether it was the fault of the moderator who led the workshop or simply the overwhelming personality of Chubby Wise, one thing is certain: Richard Seaman is close to invisible for a great part of the chapter. When the moderator finally realizes he has pretty much left Richard out of things, he allows the fiddler to talk at length about his life and music. This chapter could have benefited from some judicious pruning and rearranging. One does not need to know 15 times that the audience applauded. Is it peckish to notice such repetitions? Perhaps, but serious readers count everything, do they not? They count the number of times a word is repeated in close proximity to itself and wait to see if it is style or carelessness. They count adverbs and adjectives and puzzle why a biographer would use the personal pronoun to the point where it becomes not simply noticeable, but annoying. Still, the author is obviously a fan of Richard Seaman’s music and has great compassion and admiration for his subject’s life of sorrows and triumphs. When he speaks, Richard Seaman gives us insights into the musical and working life of his times on nearly every page. Perhaps the most valuable portion of the book in terms of getting to the heart of Richard Seaman is Chapter Four: “Your Word Was Your Bond.” It is an anthology of tall tales Richard told to students and fans of old time music to contrast the way of doing things in a large, modern city against how they were done a long time ago down in rural central Florida. The book is rich in detail and research and would be a valuable addition to any library of one interested in old time American music. As a tribute to Richard and an aid to musicians, the author transcribed and placed in the back of the book eight of Seaman’s favorite tunes, including “The Annie Seaman Waltz,” written for his wife. There is a slight irony about the inclusion of these songs. Richard Seaman, who died in 2001 at the age of 97, could neither read nor write music. Leejay Kline is a writer and teacher who lives among the alligators, wading birds, bears and snowbirds in Lake County, Florida and is happy to report that early one morning last week he spotted a coyote walking down his street. |

|

Fiddler’s Curse: The Untold Story of Ervin T. Rouse, Chubby Wise, Johnny Cash and The Orange Blossom Special by Randy Noles

(Centerstream, Paperback, 226 pp, $14.95) Reviewed by Mark M. Martin |

Fiddler’s Curse: The Untold Story of Ervin T. Rouse, Chubby Wise, Johnny Cash and The Orange Blossom Special

Reviewed by Mark M. Martin Vassar Clements, the famous fiddler from Kissimmee, Florida, refers to the Orange Blossom Special as “the fiddle player’s national anthem.” One need only Google the song to see the colossal reputation it has gained since its original 1939 recording, due in no small part to Johnny Cash who made it the title tune of his 1965 album. According to Cash himself in 1994, “In the mid 60s everybody who recorded it claimed the arrangement because no one knew who wrote it.” No one, that is, except Maybelle Carter, Cash’s mother-in-law. As the story goes, while attending the recording session, she was asked if she knew who wrote the song. Her response: “Sure I do. Ervin Rouse and his brother, Gordon. Last time I heard, they were in Florida.” Of course, the story neither begins nor ends there, and in his book, Fiddler’s Curse, author Randy Noles attempts the task of separating fact from fiction, gospel from legend surrounding the song and its original performers. Though the book is difficult to follow at times, one must give Noles credit for it is not just one story he is telling, but three: the life of arguably the most popular bluegrass song ever written, and the tumultuous accounts of two musicians, Ervin T. Rouse and Chubby Wise, who spent most of their lives “performing on a cash-and-carry basis – a practiced called ‘busking’ – in taverns, on street corners, or wherever else people might stop and listen.” Both men achieved standing ovations almost everywhere they played, and the Special continues to live on as the quintessential folk tune guaranteed to bring the house down. One of the most interesting takeaways from the book is the discovery that neither Rouse nor Wise ever even rode the train – from which the song got its name – that provided service from Miami to New York for many years and, as Noles points out, “Only the most fervent railroad nostalgia buffs seemed to care when it pulled into Miami for the last time on April 12, 1953.” The man credited with the song’s ownership, Rouse, endured tragedy, alcoholism and mental illness. According to Noles, “He spent his final years in southern Florida, sick in body and mind, plying his trade at remote roadhouses frequented by swamp denizens.” As for Wise, who claimed co-ownership of the song, Noles reports in great detail the fame he achieved as “the seminal fiddler of the bluegrass genre, [who] struggled to overcome personal demons and heal the scars of childhood abandonment and abuse.” As explained in the preface to the book, “There are those who claim that fiddlers behave strangely because they continually breathe in rosin dust that accumulates under the strings and between the f-holes, thereby affecting the brain.” Considering Rouse, the most tragic of the two creators, one can’t help but wonder about the authenticity of this claim. Rouse, who began his career as a child vaudevillian, was also known as a “trick-fiddler,” and at the age of nine could play the instrument behind his back and make music by sliding his fiddle up and down a bow tucked between his knees. As you read Noles’ account of Rouse’s turbulent life, one can’t help but ponder the similarities between the forlorn fiddler and the infamous Italian violinist, Niccolò Paganini, who was believed by his contemporaries to have sold his soul to the devil for his unbelievable abilities. What’s that? Is Charlie Daniels mentioned in the book? You’re darn tootin! Everybody who’s anybody in bluegrass music graces the author’s stage. For dedicated fiddler aficionados and bluegrass historians, Fiddler’s Curse is a must read. As evidenced by the exhaustive research Noles put into his subject matter, one can learn a little bit about everything having to do with the song and bluegrass music from the time of the tune’s creation in the late thirties to the present. For those readers who, like me, have never had the opportunity to see the song performed live, YouTube has countless versions, including Cash’s 1965 rendition and Vassar Clements who can be found there performing the song with The Del McCoury Band. What’s more important? Song or subject? Read this book, and rosin up your bows, my friends. Mark M. Martin is a poet and business writer who lives in Hollyweird, Florida with Lily, the indoor/outdoor cat his ex-girlfriend left behind. |

|

Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida by Bobby Braddock

(Louisiana State Univ. Press, Hardcover, 271 pp., $24.95) Reviewed by Gene Hull |

Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida

Reviewed by Gene Hull Bobby Braddock has had a successful career as Country Music songwriter and producer. This memoir of his early years—up to age 24, before he relocated from central Florida to Nashville—is his first venture into book writing. He was “born and raised” in Auburndale Florida, colloquially known by folks in “those parts” of central Florida as Orburndale. Hence the title. Most county music fans remember “D I V O R C E,” recorded by Tammy Wynette, a number one hit on the Country Charts in 1968. In 1980 George Jones recorded “He Stopped Loving Her Today” which was chosen Country Music Song of the Year in 1981 and 1982, and voted best country song of all time by Country America readers and BBC listeners. Braddock co-wrote both of these huge hits with his friend and mentor, Curly Putnum. He also co-wrote the George Jones-Tammy Wynette duet, “Golden Ring”. His solo-writer hits include, “Time Marches On,” “Texas Tornado” and Toby Keith's #1 hit, the country-rap song “I Wanna Talk About Me”. These and many more songs and arrangements have added to Braddock’s reputation as one of best known songwriters in the history of Nashville Music Row. So how did he get there? Down in Orburndale reveals the early roots of a career, rather than progressive steps taken on the way to it. Braddock sculpts deft descriptions of his roots in his reminiscences with obvious affection. He recalls many minute details of the lay-of-the-land, who lived-where, who-did-what and who-said-what with candid humor, which, however, sometimes seem to have little bearing on who he was to become. These were days the days before the Disney invasion, theme park developments, and colossal growth of Central Florida. Auburndale was a typical cracker Old Florida town of less than 2000 people. In this environment of orange groves, small lakes, rural values, boyhood high jinks and teenage obsessions with girls, Braddock does not hold back in describing his exploits, even those which got him into trouble. Fans of Braddock may find his honest account of his young years and coming of age interesting when searching for the answer to the logical question: What influenced a young boy from a sleepy little central Florida town to eventually become a successful country music songwriter? Good question. However, you will not find a seminal event or fire-stoking career impetus in this memoir. Rather, what’s here is the life of an average coming-of-age kid who loved music, who came from a good family with caring parents, had an average country-boy up-bringing, had piano lessons for a while, enjoyed singing, radio-listening and girls—certainly an adequate beginning for a career in country music. He writes: For several years, it had been Orburndale after-school ritual to turn on the radio in the afternoon and listen to The Polk County Express over WSIR in Winter Haven… 'Blow that whistle, ring that bell, listen to that engine yell,’ went the theme song of this weekday show that played country music three days a week and pop music the other two. One thinks of a vacuum being created after something disappears, but there was a music vacuum before rock’n roll came along. We didn’t know it then, but we were waiting for it to be born… According to his account he stumbled, blundered, practiced, drank, fell in love, screwed up, and screwed his way through his late high-school-age years and for a few years after that, playing with any band he could.

When I think about this time in my life, I think of the girls (that I longed for), friends (that I had a lot of fun with), and music (that I loved). All these factors came into play when I went with my buddies to see Elvis’s first movie, Love Me Tender at the Polk Theater in Lakeland. We were gratified vicariously as the girls screamed and moaned over Elvis. When he sang ‘Let Me’, one girl sitting behind us gasped “I’ll let you, Elvis,’ This was the Eisenhower era of innocence—it was the time of the Cleavers and the Cunninghams. Yeah, right. Braddock worked in his father’s orange groves when he had no music work in Rock and Roll bands. He married, moved, moved again, but pressed on toward a goal, which only became clearer as he grew up. His target was Nashville, where he eventually relocated and one year later joined the Marty Robbins band.

Braddock’s fond memories of his youth in Auburndale, and the obvious love he has for a patient and supportive father and mother, live in the pages of Down in Orburndale. He pulls no punches and tells his story just like he writes music: with joy, sadness, humor, irony and confidence. He plans a sequel memoir about his professional life. Gene Hull is a freelance writer and author of Hooked On A Horn, Memoirs of a Recovered Musician. Learn more at his website. |