FBR Feature: Jack Kerouac

Jack Kerouac's Orlanda Blues

by Ariel Francisco

by Ariel Francisco

|

Book of Blues by Jack Kerouac

(Penguin Books. 1995, paperback, 274 pp., $16.00) |

Two of the biggest events in Jack Kerouac’s life occurred while he was in Florida: the

publication of On The Road and his sudden death in 1969. The first stint, in Orlando, stretching between 1957-58, was incredibly productive though relatively unknown to most people, perhaps foreshadowing his future and final reclusivity in St. Petersburg. Living with his mother and sister, he wrote the entirety of The Dharma Bums, as well as working on The Subterraneans and Desolation Angels. It’s interesting that while his literary life took off during his stay in the Sunshine State, it rarely comes up in his work. There are, though, some small instances of his time in Florida in the 51 Choruses of his Orlanda Blues, which is a small section in his larger collection Book of

Blues.

Kerouac’s Book of Blues is comprised of poems written in his style of “blues” in various locations, from San Francisco to North Carolina to Florida. The poems, or “choruses,” self-described as “non stop ad libbing,” were framed by the constraints of the small breast pocket notebook in which they were written and meant to be akin to the bars of jazz music. Despite their spontaneous and perhaps even chaotic nature, they seem to represent the rare, quiet moments in his life, the breaks between racing cross-country with Neal Cassidy. Naturally, some of the landscape and life situations leak into these poems. In "31st Chorus," Kerouac writes “O Gary Snyder/we work in many ways.../But O Gary Snyder/where’d you go,/What I meant was/there you go.” While this doesn’t bring in Florida directly, it’s an interesting poem when we know that Kerouac was writing this while also working on The Dharma Bums, which was based on his adventures with Gary Snyder. It’s possible that this poem was written as a precursor, the initial manifestation of his thoughts on the time he spent out west with Snyder, and after finishing it dove head first into The Dharma Bums. Or perhaps it was composed while taking a break during the writing of the novel, or even after reading a letter from Snyder, with whom he kept up a correspondence. |

This mode of poetry allowed Kerouac to write out his thought process almost seamlessly. What triggered the thought often remains mysterious, as it is here. We know that Snyder was on his mind, but what came first, the poem or the novel?

However, sometimes a poem's trigger can be deduced a little more clearly. For example, a small inner sequence that begins with the ending of 6th Chorus, “You dont know how far/that sky/go,” continues into "7th Chorus":

However, sometimes a poem's trigger can be deduced a little more clearly. For example, a small inner sequence that begins with the ending of 6th Chorus, “You dont know how far/that sky/go,” continues into "7th Chorus":

Message from Orlanda:-- His musings often turned him towards God, as most of his writing did at some point or another,and these blues are no exception. Though a tremendous observer, his eyes always wondered skyward eventually and God was seemingly always there waiting for him. These poems that transcend into the heavenly are numerous and less interesting. It’s when Kerouac keeps his gaze Earth-bound that we get real insight into his world at the time, and the liveliness of his surroundings despite it being a quiet perod in his life.

And Kerouac follows that up in "8th Chorus," reassuring us that “thats awright, space’ll carry/usmaybe like little eggs.” Given the timeframe of his stay in Orlando, we get a little more insight into what’s happening in the world at large with these lines: It’s very likely that he was viewing one of the various rocket launches (many of which failed) lifting off out of Cape Canaveral, only some fifty-odd miles away to the east. At the time, the U.S. Space Program was desperately trying to catch up to the Russians Sputnik. It isn’t hard to imagine Kerouac sitting on the porch with his small notebook, seeing the rockets streak across the eastern sky, or hearing about them on the radio and stepping out to marvel, lighting up a cigarette, one of his many cats curling its tail around his leg in affection. In "19th Chorus" we get a little snippet of Florida with “coral snakes and alligators/on the sidewalk” which becomes more ominous in "21st Chorus" when we he writes “that cat’s in paradise.../But O, Lord above,/have pity on my/missing kitty.” The literal meaning here is clear: one of his cats has gone missing and there is more than one suspect. Kerouac continually turns a suspicious eye towards the Florida wildlife, and these two culprits return later in the sequence along with a few others in "44th Chorus" when he describes a man bitten by a coral snake hiding under his bed as he gets ready for work (coral snakes are notoriously poisonous), a little boy eaten by an alligator in his yard, an old woman killed by fire ants in her sleep, and his own mother witnessing a huge lizard with “big red eyes” on the garbage pail. This final devilish creature is the most ominous of all, certainly looking for Kerouac and not his mother. The poem, perhaps ironically or perhaps dead serious, opens with a line of advice: “Don’t ever come to Florida.” Knowing that Kerouac would die in Florida, there is something foreboding about that warning and some of the final poems in general, something muddled yet prophetic. What was it about Florida? It seemed to be warning him and yet he returned. In the final, "51st Chorus" Kerouac writes: which is the way to |

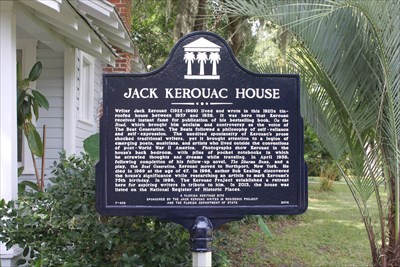

The circa 1926 house at 1418 Clouser Avenue in the College Park section of Orlando, where Jack Kerouac and his mother lived in rented rooms at the back of the cottage in 1957-58. Reporter Bob Kealing's 1997 article in the Orlando Sentinel, reporting on his investigation and discovery of the house in run-down condition, led to formation of The Kerouac Project.

The Kerouac Project, a non-profit, has restored the house, and now supports writers through residencies. Learn more about their programs to support writing in Central Florida.

|

He shouldn’t have come back. He should have taken his own advice.

Ariel Francisco is a first generation American poet of Dominican and Guatemalan descent. He is currently completing his MFA at Florida International University where he is the editor-in-chief of Gulf Stream Literary Magazine and also the winner of an Academy of American Poets Prize. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Gulf Coast, Tupelo Quarterly, Washington Square, and elsewhere, and his chapbook Before Snowfall, After Rain is forthcoming from Glass Poetry Press. He lives in Miami, FL.

Ariel Francisco is a first generation American poet of Dominican and Guatemalan descent. He is currently completing his MFA at Florida International University where he is the editor-in-chief of Gulf Stream Literary Magazine and also the winner of an Academy of American Poets Prize. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Gulf Coast, Tupelo Quarterly, Washington Square, and elsewhere, and his chapbook Before Snowfall, After Rain is forthcoming from Glass Poetry Press. He lives in Miami, FL.