Classic Florida Reads

|

On this page:

◇ Turtle Moon by Alice Hoffman, reconsidered by Natalie Havlina ◇ In the Heat of the Summer by John Katzenbach, reconsidered by Natalie Havlina ◇ A Land Remembered by Patrick D. Smith, reconsidered by Pamela Akins ◇ Cross Creek by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, reconsidered by Lauren Rivera ◇ Irving and Me by Syd Hoff and Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself by Judi Blume, reconsidered by Dina Weinstein ◇ Blood on Biscayne Bay by Brett Halliday, reconsidered by Susan Jo Parsons ◇ The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, reconsidered by Susan Jo Parsons ◇ Stick by Elmore Leonard, reconsidered by Nick Garnett ◇ Everglades River of Grass 60th Anniversary Edition by Marjory Stoneman Douglas, reconsidered by Jennifer Hearn ◇ The Barefoot Mailman by Theodore Pratt, reconsidered by Gwen Keenan ◇ The Corpse Had a Familiar Face by Edna Buchanan, reconsidered by Susan Jo Parsons |

Elsewhere on FBR:

On our Florida SF/Fantasy page, see Daniel Santos' reconsideration of Neil Gaiman's Anansi Boys, and Frank Tota's reconsideration of Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank. |

Turtle Moon by Alice Hoffman, A Reconsideration by Natalie Havlina

|

Turtle Moon by Alice Hoffman

(Berkley Books, Paperback, 275 pp., $13.00) Turtle Moon

(G.P. Putnam & Sons, Hardcover, 1992) Turtle Moon

(Brilliance Audio, August 2009) |

I first encountered Alice Hoffman in the summer of 1993. My mother and I were on the 1,100 mile road trip from our house in southwestern Idaho to my grandparents’ farm in northeastern Montana and the book on tape we listened to was Hoffman’s Turtle Moon. It enchanted us. A boy and a baby girl were on the run together, hiding under a culvert in a place where the heat was so intense it melted the pavement, the kind of heat that I could only imagine as a superlative, even while I was sitting in a car that had been driving across the prairie for eight hours on a sunny, July afternoon. Mom and I would talk about Turtle Moon for years to come, the strange beauty of that short, sweet book, and how we should revisit it sometime. We never did, because we lost the tapes. Fast forward twenty-five years. Mom is under the knife, midway through a surgery scheduled to last eight hours. I am waiting outside the hospital’s patient library, listlessly scanning a cart of used books for sale. I am expecting nothing, not even a momentary reprieve from anxiety. And there it is: Turtle Moon. Grabbing the book is not a rational decision; it’s a reflexive response to a leap of joy. Only in the next second do I rationalize buying the book. I will get it for Mom, maybe read it to her once she starts feeling better. In the meantime, Turtle Moon’s surreal cover can decorate her room in the ICU. The book won’t even require a card; Mom will know who it is from and what it means, everything it means. Two hours later, the surgery is taking longer than expected. I open Turtle Moon, skim the first page, and stop in surprise. How could I have forgotten? The story takes place in Florida. The bizarre, magical place that has been etched in my memory for the last quarter of a century is Florida, the same place where I have landed unexpectedly to pursue an MFA. Maybe I’m supposed to be there, after all. *

Originally published in 1992, Turtle Moon was Hoffman’s ninth novel and won the International Association of Crime Writer’s Dashiell Hammett Prize for Literary Excellence in Crime Writing. It was released in paperback in 1993 , reprinted in 1997, and reprinted again in 2002. New copies of both the hardcover and the paperback are still available, as is the audio version published by Brilliance Audio and narrated by Sandra Burr. Of course, Brilliance has discontinued the cassette tapes that Mom and I listened to. Now the book’s on Audible. Although, as Publisher’s Weekly pointed out in its 1992 review, Turtle Moon would make a “wonderful movie,” and Universal optioned the rights, a film has never been made. Turtle Moon takes place in Verity, “the most humid spot in eastern Florida,” where it’s so quiet you can hear strangler figs dropping onto car hoods and the air is so thick that neither cigarette smoke nor departing souls can rise. It’s May, and, as everyone in Verity knows, “Every May, when the sea turtles begin their migration across West Main Street, mistaking the glow of the streetlights for the moon, people go a little bit crazy.” This year, the May craziness includes the murder of Bethany Lee, a young mother hiding from her wealthy, soon-to-be ex-husband under an assumed name. Bethany’s ex sends a hit man to find her, kill her, and bring their twelve-month-old daughter, Rachel, back to New York. The scheme goes awry when twelve-year-old Keith Rosen, “the meanest boy in Verity,” finds the baby alone in the laundry room of their apartment complex and, hearing shots and screams from Bethany’s apartment, runs away with the baby. Keith’s disappearance makes him a suspect in the murder, leading his mother, Lucy, to undertake her own investigation. Her attempts to clear her son eventually lead her into a reluctant partnership with Julian Cash, a K-9 handler for the Verity Police Department, who is haunted by the death of his cousin twenty years before. Reading Turtle Moon for the second time, as an adult, was even more rewarding than listening to it as a child. Reading meant that I could jump up and grab a pencil (I tired of that quickly and read with pencil in hand) to underline my favorite passages. I wanted to carry with me Hoffman’s images of a twilight sky “full of heat waves and parakeets,” midnight stars turning red with the heat, a swaying wind chime that sounds like a falling star. Then there’s Florida. Now I know how, “In weather like this the air turns into waves, and those waves break down into sharp white circles, so you feel that you’re surrounded by stars in the middle of the day.” Experience has also given me greater insight into the characters. The first time around, I was most interested in Keith’s adventures with the baby. Now I’m the same age as Lucy. Like her, I’ve gazed at an invitation to my twenty-year high school reunion and felt, “shivery, and somehow embarrassed, as if, after twenty years, when the facts of her life should all be settled, she hasn’t even begun.” Far from diminishing the power of the story, the disillusionments of adulthood have made the wonders of Turtle Moon all the more precious. I recommend the book to anyone looking for, or willing to see, the magic in the everyday, especially in the heat of Florida. Natalie Havlina is a recovering environmental litigator teaching and writing in her hometown of Boise, Idaho. She received her Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from FIU and is a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. |

Classic Florida Crime:

In the Heat of the Summer by John Katzenbach, A Reconsideration by Natalie Havlina

|

In the Heat of the Summer

by John Katzenbach (Scribner, Paperback, 320 pp., $19.00) Reviewed by Natalie Havlina |

The hardcover copy of John Katzenbach’s In the Heat of the Summer sitting beside my laptop looks older than it is. The red cover is faded from the sun and the gold lettering on the spine is worn. The first time I opened it, Chapter 1 and half of Chapter 2 separated from the spine and fell into my lap. Chapters 3 through 19 attempted similar escapes while I was reading. The book’s worn condition is probably the result of extensive use as much as age. Published in 1982, In the Heat of the Summer was nominated for the Edgar Award and launched Katzenbach’s career as a successful author of psychological thrillers. In 1985, a film adaptation starring Kurt Russell and Muriel Hemingway appeared as The Mean Season. The story begins in 1975 with the discovery of a sixteen-year-old girl’s body, bound and shot in the back of the head, execution style. Protagonist Malcolm Anderson, reporter for the fictional Miami Journal, scoops the story and sets out in search of further material, putting the book on what appears to be a standard amateur sleuth path. Then the killer calls. He’s got a point to make, and his teenage victim is only “Number 1.” As the murderer continues his kill-and-call routine through the summer, Anderson investigates, reports, and bears the killer’s message to the public. Anderson faces an increasingly urgent professional dilemma: “Are we covering [the story], or are we participating in it?” Or is it enough to say that, if Anderson’s paper stopped printing the story, “The competition, the television, the wires, everybody would be all over it. We would be alone.” The killer’s phone calls are instrumental to the novel’s suspense and its many twists. Every fresh kill and every telephone conversation increases the tension until, as the New York Times has said of one of Katzenbach’s later novels, “Only a bomb going off could pull you from the book.” For me, the book’s 1975 setting is part of its appeal. I was fascinated by the technical problems that Anderson and the police face. When Anderson suggests tracing the killer using a wire tap, for instance, the police detective laughs and accuses him of watching too much TV. “Even with computers and all of the fancy electronics equipment developed in the war, it would still be better, we would stand a better chance of interrupting calls at random around the city to see if we happened to stumble upon the killer.” Quaint technology notwithstanding, In the Heat of the Summer explores issues that are just as relevant today as when the book was published thirty-five years ago. The killer is a Vietnam veteran who claims that he can’t get adequate medical care from the Veterans’ Administration. While this does not appear to be the killer’s only problem, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and shortfalls in veterans’ services are hardly things of the past. Nor has the threat of random violence abated, as questions surrounding the shooting at the Fort Lauderdale airport this past January reminded those of us in South Florida. As a suburban mother interviewed by Anderson says, “It’s like an invasion of invisible enemies. You know that they’re out there, but you can’t see them to fight them, and that’s what makes me so scared.” My favorite part of the book is the killer. His methods are psychological, more subtle than the sexual assaults or torture favored by some villains, and he is smarter than many of his counterparts. He plays the public, he plays Anderson, and he played me. I encourage everyone who enjoys mystery and suspense to take a look, or take another look, at In the Heat of the Summer. It’s still in print and can be ordered as a paperback, but I hope the library will set up an appointment for the well-loved copy I’ve been reading with a book binder, or at least apply some glue, so that other patrons can enjoy it. Natalie Havlina is a teaching assistant in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Florida International University and a Florida Book Review Contributing Editor. Prior to coming to FIU, Havlina spent a decade practicing public interest law in the Northwest. |

A Land Remembered by Patrick D. Smith: A Reconsideration by Pamela Akins

|

A Land Remembered

by Patrick D. Smith (Pineapple Press, 403 pages, Hardcover 19.95, Paperback 14.95) Covers of the two-volume student edition, widely taught in Florida schools.

|

After reading my review of the picture book, Enchantments, an 80-year-old native Floridian urged me to read A Land Remembered, even loaning me her copy. Now, like her, I think every newcomer to the Sunshine State should read this 1984 action-packed saga of the taming of the Florida frontier. It not only offers a glimpse of what has come before, but what we are fast losing.

Winner of the Florida Historical Society’s Tebeau Prize for the most outstanding Florida historical novel, voted Florida Monthly readers’ favorite book for 10 years, and still taught in Florida schools, Smith’s iconic tale covers over 100 years of Florida history through three generations of the MacIvey family. Dirt-poor, honest and hardworking, they manage to survive and eventually thrive in a place of unforgiving heat, wild predators and human greed. The story begins in 1968 with Sol MacIvey ruefully surveying Miami Beach and family land he’s developed west along the Tamiami Trail. It then goes back to 1863 when Tobias and Emma MacIvey with their son Zech are eking out a living in Florida’s northern scrub country. They get by with a small garden, wild game killed with his front-loader shotgun, and supplies traded for animal hides at a small settlement on the St. John’s River. When Tobias is conscripted to deliver cattle to the Confederate army, he’s given a whip to keep the cows in line and becomes a proficient “Cracker.” After the Battle of Olustee, he claims a dead soldier’s horse and heads home, where he finds his cabin burned and oxen slaughtered by rebel deserters. Tobias gathers his wife and son and moves south, establishing a new homestead near the Kissimmee River. Idealistically portrayed, the MacIveys are kind, honorable and industrious. They befriend starving Seminoles, hire a runaway slave as ranch hand, and do thousands of dollars worth of business with just a handshake. They round up and drive wild cattle to Punta Rassa for shipment to Cuba and plant orange trees for steamers shipping fruit north. Tobias builds his own home from cypress logs, while Emma harvests wild greens, grinds flour from cattail roots, and cooks ‘coon stew to keep her family from starving. They are strong and resilient, surviving hurricanes, flash floods, and malarial mosquitoes. When rustlers ambush the family and kill Zech’s beloved Seminole wolf-dogs, Tobias tells him: “What you just seen and been through will come again and again. This whole wilderness is built on such as that, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better, if it ever does. You’ve got to learn to take the bad as well as the good, no matter what comes along. . . . Don’t be afraid or ashamed to love, or to grieve when the thing you love is gone. Just don’t let it throw you, no matter how much it hurts. If you make it in this wilderness, you got to be strong.” To get it right, Smith interviewed old Florida ranchers for years before creating his prototypical pioneers. In addition to documenting the peculiarities of Florida frontier life—no Western herd was ever wiped out within hours by swarms of mosquitoes—the book introduces a Florida-specific vocabulary: yellowhammer cattle, marshtackie ponies, koonti flour, swamp cabbage, Pay-Hay-Okee. And its descriptions of the wilderness, like Zech’s first glimpse of Lake Okeechobee, can be stunning:

The shimmering surface stretched into the horizon and gave no hint of a distant shore. Vast areas of blooming pickerel weed lined the water’s edge, creating a sea of soft blue that merged gently with clumps of willows and little islands of buttonbush with its creamy white flowers. Nearby rookeries exploded with birds, great blue herons and snowy egrets, white herons and wood ibises, whooping cranes and anhingas with the wings spread outward to dry them. Cormorants dived beneath the surface and popped up unexpectedly fifty feet away, startling flocks of ducks and coots that peppered the surface. Majestic roseate spoonbills stalked up and down the shallows, swishing their long paddle bills from side to side as they raked the bottom in search of food, their pink feathers catching the sunlight and making them appear even pinker. When Zech asks, “Pappa, who owns all this land out here?” Tobias answers, “The Lord.” By the time Zech’s son Sol takes on the family business, these values have been lost. This seems to be Patrick Smith’s ultimate message: if we are not careful, there will be nothing left of Florida’s original fierce beauty.

A Land Remembered conjures up Florida’s colorful past and asks us not to forget what once was, what is gone forever. Pamela Akins is creative director of Akins Marketing and Design, and, although a born and bred Texan, she now lives in Sarasota, FL and New London, CT.

|

Cross Creek by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings: A Classic Florida Memoir Reconsidered by Lauren Rivera

|

Cross Creek by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

(Simon & Schuster, Paperback, 380 pp., $17.00) |

Classic Florida Memoir

Cross Creek by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings A Reconsideration by Lauren Rivera Moving to Gainesville from Miami led me to read Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ 1942 memoir set in the same county. Cross Creek, about Rawlings’ frontier life in the segregated backwoods of Alachua County, Florida, in the 1930s contributes to great American literature about space and race. In her memoir, Rawlings uses an inheritance to purchase an orange grove which she envisions profiting from in the background while she devotes herself to writing novels. But that kind of isolation proves impossible, as the grove has been a major employer in an area surrounded by families who subsist on fishing, hunting and seasonal labor. Her urban, New England life has inadequately prepared her for employing laborers, training help or resolving disputes over wandering livestock. She prevails, thanks to the advice and intervention of neighbors, her ability to write about the experience, and her gun. Cross Creek provides the timeless pleasure of exploring the natural environment. Passages devote careful attention to the song of bird calls, the joie de vivre of ducks, the gentlemanly manner of rattlesnakes, the symmetry of magnolia trees, and the sun beaming through orange groves. Her pristine prose is ripe with sensory detail and emotional impact. “To hear a panther scream is to add a new horror to the catalogue of evil,” Rawlings writes. “It is the shriek of a vampire woman, an insane shrill tremolo, half laughter and half moan.” Complementing her precise use of detail, Rawlings spells dialogue the way she heard it. “Oh Sugar,” says Martha, her housekeeper, “I knows you tired in the arms.” Her neighbor, Floyd Townsend, declares, “We bought us an ottymobile.” This use of vernacular helps Rawlings present characters in a way that feels authentic. However, Rawlings’ own character descriptions are sometimes troublesome. She uses “Negress” and “Pickaninny,” which were accepted terms in the 1930s South, but it doesn’t sound endearing today when she refers to a small child's hands as "careful black paws." The reader will stop short when Rawlings writes, “Preacher is a wizened little chimpanzee of a negro, his hands swift as the claws of a hawk among the oranges.” I think it helps to recognize Rawlings as a product of her time and place. Furthermore, she redeems herself somewhat by asserting that, “There is no hope of racial development until racial economies are adjusted,” evoking a more progressive, anti-segregation sentiment, and demonstrating that she supports creating opportunities to elevate the black race. Rawlings also gains credibility by emphasizing the ways her environment and her neighbors impact her, over her impact on them. The reader will appreciate her confessional tone. For example, Rawlings becomes self-conscious around other physically fearless women: “I felt feeble minded to find myself screaming at the sight of a king snake that asked nothing more than a chance to destroy the rats that infested the old barn." She acknowledges the futility of her attempt to treat children who were gray with hookworm, departing “with the sense of smugness common to all meddlers." The reader’s payoff comes largely from her pioneering spirit; Rawlings is able to study, observe and absorb her surroundings, without the intention to squander or exploit. Throughout, Rawlings is enamored of and deferential to her environment, stating that, “a part of the beauty is the fight to keep it, and that all good things do not come too easily and must perpetually be fought for. Our test is in our recognition of our love and our willingness to do battle for it.” Anyone who must adjust to a new environment will understand the challenges that Rawlings faces in Cross Creek. Mastering cuisine that includes palm hearts or rattlesnake she shows her determination, and ultimately the ways she and Cross Creek match each other. She survives. She stays. And the best signifier of her triumph is her transcendence. After changes in water levels render her map useless, she still embarks on a journey through various lakes, channels and marshes, seeking the St. Johns River. I thought, “This is fantastic. I’m about to deliver myself over to a nightmare.” In my two years here, I’ve come to see that Gainesville upholds the tradition of relocating here to develop intellectually alongside nature. Around these parts, we are in good company with Rawlings as we take the nature trails that run though the University of Florida’s campus. Graduate students grow vegetables with homemade compost and trade the surplus at the local farmer’s market. Graduate advisors, who recommend exercise along the Hawthorne Trail, forewarn: beware the cottonmouth. Rawlings would add that "there is a healthy challenge in danger, and a spiritual sustenance that comes from it."

Lauren Rivera, a native of Miami, received her MFA in Creative Writing from Florida International University. Gainesville is the new setting of a growing family, teaching secondary Language Arts, and plenty of reading and writing. |

Classic YA About Moving to Miami

|

Irving and Me by Syd Hoff and Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself by Judi Blume

A Reconsideration by Dina Weinstein From afar, Miami is a magical place, but moving here is not always that magical. It can be full of awkward moments, as I know from experience. That transition to Florida is the subject of Irving and Me (Harper & Row Publishers, 1967) by Syd Hoff and Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself (Random House, 1977) by Judy Blume. Both books are geared to middle grade readers who themselves are on the cusp of change. I first read Starring Sally in the 1980s as a middle school student in Boston who would vacation with my snowbird grandparents in Miami Beach. And, now a local, I came upon Hoff’s out-of-print book while curating a 2012 centennial exhibit on him to accompany the dedication of his Miami Beach home as a Florida Literary Landmark. I acquired my copy of the out-of-print Irving and Me as it was being de-accessioned from a local library. Struck by their approaches to dislocation, I became interested in reconsidering Starring Sally and Irving and Me together. The books have similar plots: Jewish kids from the New York/New Jersey area have to readjust to life in Miami. Both books document Jewish cadences, worrywart Jewish mothers, Jewish foods and Yiddish expressions. I relate to the characters grappling with issues of class-differences. Hoff and Blume address relocating, fitting in, powerlessness, self-doubt and greater world events. The books are part-autobiographical, as both authors were transplants themselves. Hoff is best known as an author/illustrator of picture books Danny and the Dinosaur (1958) and Sammy the Seal (1959) and a cartoonist for The New Yorker. Irving and Me was Hoff's only young adult book and, despite the author's popularity, his only work to earn recognition by The New York Times as a top children's book. The Bronx-born Hoff moved to Miami Beach in the mid-1950s, in his mid-forties, when one of Hoff’s daughters injured her hip and Miami Beach’s balmy climate was supposed to help her convalesce. Hoff remained here and died in 2004. Hoff's protagonist, Artie, moves because Brooklyn becomes too tough and the family thinks Florida will be better for his mother’s arthritis. Hoff skims over some of the heavy-duty issues, namely that Artie’s family flees Brooklyn because blacks and Hispanics are moving into the neighborhood, creating ethnic frictions. He alludes to the civil rights struggle and also mentions race riots, a timely topic in 1967. Hoff dances around issues of white flight and the mixed feelings Jews had about leaving vibrant urban neighborhoods for boring suburbs, even though these offered more space to spread out. The characters are clearly all-American but are still figuring out how much to wear their Jewish identity on their sleeves. In Irving and Me, thirteen-year-old Artie arrives in Sunny Beach and has a hard time adjusting. Hoff captures the transplant’s feeling of isolation when Artie thinks: Why can’t kids see when there’s a stranger in town and take time out to make him feel at home? Someday I’m going to make that my life’s work - saying hello to kids the minute they arrive from someplace. Soon, Artie meets a local boy, Irving, on the beach. The two boys hit it off and become fast friends. The book describes the friendship progressing and Artie adjusting to his new town with a number of tense moments, disagreements, and misunderstandings as well as regular dealings with the neighborhood bully. The two buddies spend the summer attending activities at the neighborhood community center, taking guitar lessons, and romancing neighborhood girls.

Judy Blume is best known as the author of dozens of middle grade books dealing with teenage angst like Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. (1970), Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing (1972) and Blubber (1974). Blume lived in Miami Beach in 1947, the year she turned ten in the wake of World War II, a concept that looms large in the story. She wrote Starring Sally as an almost 40-year-old. Sally moves to Miami Beach for a year with her mother and grandmother, leaving her dentist father behind in New Jersey for her brother's health. When I first read Sally, the book spoke to me, showing me what it would be like to live in this place I only knew as a vacation spot, a locale that was bright and warm while it was dark and frigid in my hometown. One scene gave me pause. Etched in my memory is Sally feeling uncomfortable in the bathrooms at her new Miami Beach school because there were no stall doors. I’ve never seen that here, but I bet my Chicago-born sons have their own story to tell of things that seem not quite right. The fact that Sally is still in print is a testament to the author’s skill at portraying complex characters, her extensive body of work, and the intriguing subject matter. Sally’s character is more out there than Artie. She is more bluntly fearful and suspicious than Artie was. Sally is afraid her father is going to die because he is exactly the same age as his two brothers were when they died, and "bad things happen in threes." She thinks an elderly neighbor is really Hitler hiding in plain sight. She constantly thinks about a cousin who was murdered by Nazis. In the book, the ten-year-old protagonist changes from little, obedient girl to a more independent person who questions her mother’s beliefs, forges new friendships, and furtively listens to the neighbor’s conversations on the apartment building’s telephone party line with her grandmother’s knowledge. Like Artie, she too forms a first relationship that goes as far as a kiss. Both books convey a sense of amazement about Florida, which symbolizes a new leaf for the characters. On her way to her new school, Sally snaps a big red flower off a bush and tucks it behind her ear like her favorite movie actress, swimmer Esther Williams. Artie sweats out the blistering summer heat, marvels at the salamanders scurrying freely about and dreads pools and beach meet-ups because he can’t swim. Spoiler alert: In the end Sally goes back to New Jersey, while Artie gets a dog and stays in Sunny Beach declaring, “I think I’m beginning to like Florida. Really like it.” Surely, a modern-day Artie or Sally is out there, having come from a Spanish-speaking country or Haiti or Chicago, with his or her own story to tell of moving and adjusting to Florida, its challenges and appeal, under a big canopy of current events, shaded by bright, red poinciana trees. To Learn More:

Official Judy Blume website. Official Syd Hoff website. The Syd Hoff Literary Landmark at his home in Miami Beach was dedicated Feb. 10, 2013. Read more about the Florida Literary Landmarks. |

Classic Florida Crime

|

Blood on Biscayne Bay by Brett Halliday

(Originally Published 1946. Out of print.) |

Blood on Biscayne Bay

A Reconsideration by Susan Jo Parsons The irony of Blood on Biscayne Bay by Brett Halliday is that the book describes a time long ago, but the off-the-wall characters and places could easily be found in modern day South Florida. The setting is 1945: With the end of summer, the Magic City’s tempo was quickening. This was the first “Season” since peace had come to a war-weary world, and already tourists were crowding in, eager to spend their inflated money and clamoring for the frenzied gaiety which Miami knows so well how to offer. Mike Shayne, a private eye, is enjoying a vacation in Miami, partly in order to escape his confusing feelings for “Lucy Hamilton, his attractive secretary in New Orleans.” His vacation is soon interrupted by a visit from Christine Hudson, a friend of Shayne’s wife, Phyllis, who passed away a few years before. Christine is in trouble and she needs Shayne’s help and his loyalty to his departed wife makes it impossible for him to refuse.

“$10,000 by Midnight” is the title of Chapter One, and that’s what Christine needs Shayne to deliver. She is being blackmailed by Arnold Barbizon, the crooked owner of the 20-acre casino near 79th Street on Miami Beach called the Play-Mor Club. Christine explains she has racked up a gambling debt, and she can’t risk her high society husband finding out. She’s made a replica of a valuable pearl necklace her husband gave her, and she asks Shayne to sell the real pearls and deliver the cash to the blackmailer. Shayne, however, figures the young lady is being treated unfairly, and instead roughs up Barbizon, grabbing the I.O.U. in the process. When he bolts from the club, he shares a cab with a sexy young blonde who is also in a hurry to get out of there, and the taxi drops her off at Christine Hudson’s house of all places. The next morning reveals the young blonde to be Christine’s housekeeper, and she’s dead—murdered shortly after the taxi dropped her off. As a private eye who sometimes bends the rules to get results, Shayne has an uneasy relationship with the local cops, particularly Peter Painter, the Chief of the Miami Beach Detective Bureau. Shayne quickly discovers that Christine wasn’t completely honest with him, and when Painter finds out Shayne is peripherally involved, Shayne soon becomes a suspect. If he doesn’t sort the mess out himself, he’ll never make that plane he keeps postponing back to New Orleans. A group of shady characters emerge, including Christine’s husband, her former boss, and his sultry wife, an unscrupulous reporter, a local private eye and a crabby cab driver. The best character is the former boss’s wife, Estelle Morrison, who Shayne meets as she is sunbathing behind her house, wearing “a wisp of flowered cloth over her pointed breasts, and a triangular piece of the same material for a loincloth. . .” Her first husky words to Shayne are, “Do you approve of what you see?” Shayne is no fool, though, and doesn’t mess with this femme fatale, except to give her a Cognac and Cointreau mixture that makes her pass out so he can slip away from her. One of the most delightful aspects of this book is the geography. Shayne zips around the city in stolen cabs, up and down Collins. He spends time on boats crossing Biscayne Bay in the wee hours of the morning. He swims up shore to sneak into the back beach entry to the Play-Mor Club unnoticed. As a former resident of Miami Beach, I found myself trying to picture where a club like the Play-Mor could have been located and visualizing Shayne’s midnight passages across the Bay. Shayne is a tough-talking smart aleck but you clearly see his soft spot as he dodges going back to New Orleans to face the romance developing with Lucy or as he reflects on the loss of Phyllis. It is a pleasing mixture that makes for a protagonist one can root for. Blood on Biscayne Bay is out of print, but copies are available online, and well worth the search. Susan Jo Parsons is the founder and publisher of The Florida Book Review. |

|

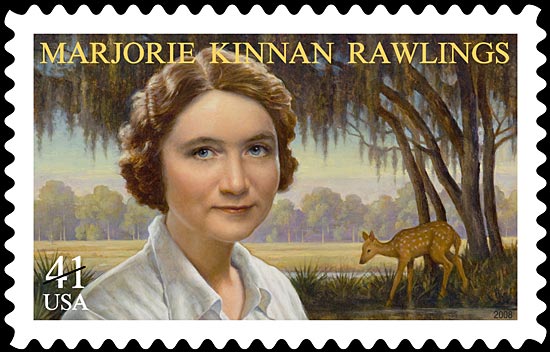

The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

(Aladdin, Paperback, 528 pp., $5.99) A Reconsideration by Susan Jo Parsons |

The Yearling: 70 years later—a glimpse of old Florida

A Reconsideration by Susan Jo Parsons Before Scout Finch became the precocious narrator of To Kill a Mockingbird, there was Jody Baxter, the ten year-old hero of The Yearling. Author Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was a protégé of Maxwell Perkins, the editor from Scribner’s who aided the careers of Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Rawlings held her own among those literary giants--The Yearling, published in 1938, captured the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1939. Now, the book is a staple on Florida high school reading lists, but it mustn’t be dismissed as a tale for school children. It preserves post-Civil War pioneer life in Florida as well as offering the reader a nostalgic look at childhood.

The Yearling is set in the wilderness of northern inland Florida. Jody Baxter lives in a small, isolated house with his parents. His mom, Ora Baxter, is a large, hard woman with sharp words for her son. You soon forgive her, though, because you witness her really roughing it—water has to be hauled to the house from a nearby sink hole, she has no other women to share her household duties and she lost several children at early ages. Jody is the only of her children to survive. Penny Baxter, Jody’s small-framed but tough father, is a bit more indulgent with his son, and strives to teach him the ways of survival in their harsh landscape. Penny’s lessons don’t end at how to hunt or how to cultivate—he strives to teach Jody how to be a good man. The dialogue is a bit tedious at first since it’s an odd mixture of formal English and backwoods speech. But you soon grow accustomed to the language. Jody and his father set off to hunt down a dangerous bear, Old Slewfoot: "You’ll not be scairt when we come up with him, Pa?” Trouble is aplenty—mostly from the hard blows Mother Nature delivers. Old Slewfoot repeatedly attacks the Baxter’s small homestead, killing their livestock, and a flood destroys the crops. The family survives these hardships only because of Penny’s perseverance.

Further trouble arises from the Baxter’s nearest neighbors, the Forresters, a wild, hard-drinking bunch. While Penny is a model of patience and good values, the Forresters are quick to stir things up. When hardship strikes one family or the other, however, the other family immediately pitches in to help, despite their uneasy relationship. It’s the only way to survive on the unforgiving frontier. The Forrester family provides Jody with the only playmate his age, Fodder-wing, a sickly boy who has a gift for caring for wild animals. Fodder-wing’s exotic pets inspire Jody to adopt an abandoned fawn, Flag. Flag and Jody are soon inseparable, and as boy and fawn travel the forest, they enjoy the freedom of childhood and learn the sometimes costly consequences of childish mistakes. The Yearling explores the inevitability of growing up and losing the magic of wonder childhood holds: …Sunset was coming a little earlier, and at the corner of the fence row, where the old Spanish trail and turned north and passed the sink-hole, the saffron light reached under the low-hanging live oaks and made of the gray pendulous Spanish moss a luminous curtain. The Yearling has one of the best novel endings I have ever read—it is bittersweet, like life. You could call The Yearling a coming of age story. Or even a man versus nature story. Or possibly a Florida history book. I call it a love story, about love for family and home.

Susan Parsons is publisher of The Florida Book Review. |

|

Stick by Elmore Leonard

(Harper Collins 2002, Paperback, 401 pp., $7.50. Originally published by William Morrow, 1983) A Reconsideration by Nick Garnett |

Stick: Once Upon a Crime

A Reconsideration by Nick Garnett In order to appreciate Elmore Leonard’s raucous and satisfying 1983 crime thriller, Stick, one must recall that the Miami of the early 80s was spinning its wheels and looking for traction. The era of the 60s hipster and rat-pack was long over and Don Johnson and his white Armani jacket were a year away from painting the town pastel, creating the slick mystique that would put Miami back in the fast lane. Though the TV show had not yet aired, there was plenty of vice in Miami. An assortment of high rollers and lowlifes trolled the town, scamming, making deals, and looking for the next big score.

Yes, it’s a crooked town, and in Stick, Leonard populates it with his characteristic mix of vividly-portrayed kingpins, oddballs and schemers, including the villainous Chucky—“big all over, high-waisted, narrow through the shoulders, the broad hips of a woman . . . and a sagging crotch”—a hyperkinetic, dope-wholesaling ‘Nam vet (a precursor to deranged Iraq War veterans who are now beginning to populate contemporary thrillers) looking to get out of the game, who barely fends off his post-traumatic stress disorder with a steady diet of Quaaludes, and Nestor Soto, a Cuban-American mob boss who’s not above practicing Santeria rituals on humans as well as chickens. When a $200,000 coke deal with Nestor goes bad because Chucky inadvertently sends an undercover cop to make the buy, Nestor demands more than his money back; he wants a pound of flesh. Chucky agrees and arranges for one of Nestor’s bad boys, Eddie Moke, a skinny, laconic, reptilian, Stetson-wearing sociopath, to make sure whomever Chucky sends with the $200,000 won’t come back. Enter our protagonist, Ernest Stickley (Stick), a cagey, 42-year old small-time car thief, fresh out of prison for armed robbery. Stick has drifted down to Miami for a fresh start and proximity to his adolescent daughter whom he hasn’t seen since being sent up. Rainy, one of Stick’s jailbird buddies who now works for Chucky, convinces the reluctant Stick to be his back-up bag-man to return Nestor’s money. What neither of them knows is that Chucky has offered up Stick to Nestor as payment in full. Fortunately for Stick, things don’t go as planned and it’s Rainy who’s gunned down, an outcome that satisfies Nestor and Chucky, but not Stick, who barely escapes with his life and goes on the lam down in South Beach. (Yes, South Beach. Back then, Ocean Drive was low rent, populated mostly by seniors squeaking by on Social Security.) Leonard’s lead characters are often driven by their own moral code (in this case prison born) and it’s Chucky’s betrayal of Rainy (not to mention the five grand he was supposed to pay) rather than seething personal vengeance that motivates Stick to get even. Wily as he is, Stick, a practically broke, middle-aged ex-con, disoriented by and out of touch with the free-wheeling vibe he encounters in Miami, could do with some help and a little coaching. Stick is a quick study, though. All he needs is a break or two, which Leonard provides (along with a dose of social commentary) in the form of more whacky, deliciously-described characters. There’s Barry Stamm, a would-be-wise-guy millionaire investor who, upon deducing that Stick was about to steal his Rolls, hires him to be his chauffeur and puts him up at his fabulous Bal Harbor compound where he meets the houseman, Cornell Lewis. When Cornell, also an ex-con, isn’t performing “freaky-deaky” Nubian slave fantasies with the lady of the house, he’s displaying a wry and practical outlook on his surroundings. It’s Cornell who suggests that Stick pay attention to the house’s comings and goings and learn something. “Learn what?” asks Stick. “I don’t know. Something,” Cornell says, “There must be something you hear listening to all these rich people can do some good.” That something is provided by Stick’s love interest, Kyle McLaren, a long-legged, successful investment consultant who’ll eventually help Stick try to beat Chucky at his own game. Unfortunately, in falling for Stick even after he tells her his past includes murder, Kyle, a fresh-faced idealist with a brother in the FBI, also sets off the reader’s implausibility alarm. This is only a road bump, however, in a story which for the most part stays in the passing lane from beginning to end. Along the way, Stick manages to make a point or two about our desire and ability to reinvent ourselves. Elmore Leonard couldn’t have known it 1983, but the city in which he chose to set his story would do a pretty good job in that regard. Nick Garnett lives in Miami Beach and continues to write about it in his memoir. |

|

Everglades River of Grass 60th Anniversary Edition by Marjory Stoneman Douglas

(Pineapple Press, Hardcover, 447 pp., $19.95) A Reconsideration by Jennifer Hearn Online resources for more information on Marjory Stoneman Douglas:

Marjory Stoneman Douglas Biography Douglas' Friends and Peers |

Everglades River of Grass 60th Anniversary Edition by Marjory Stoneman Douglas

A Reconsideration by Jennifer Hearn Marjory Stoneman Douglas opens The Everglades: River of Grass with a straightforward yet compelling sentence: “There are no other Everglades in the world.” This year, which marks the 60th anniversary of River of Grass, we celebrate the words of Ms. Douglas, which galvanized a nationwide movement to protect a region of the earth that, although teeming with life, was seen by the world as a wasteland. Because of her and other advocates’ commitment to bring the world’s attention to this miraculous river of sweetwater and sawgrass, the Everglades is no longer a moribund ecosystem. It has a pulse, although still very quiet.

The Everglades stretches one hundred miles from Lake Okeechobee to the Gulf of Mexico and is up to 70 miles wide. Originally when rain poured into Okeechobee it was propelled by way of rivers, creeks, rivulets and other water systems. “The Whole system,” Douglas writes, “was like a set of scales on which the forces of the seasons, of the sun and the rains, the winds, the hurricanes, and the dewfall, were balanced so that the life of the vast grass and all its encompassed and neighbor forms were kept secure.” Douglas first brings to life the Everglades when it was still an unspoiled river enclosing diversity. In language as rich and dense as the flora and fauna that crowded the jungles of the Everglade’s Ten Thousand Islands, she writes of the gnarled trunks of the custard apple, the ephemeral life of the chizzle winks, the creeping of the moonvines and the luminescence of their white blossoms at night. We can feel the pressure of the strangler fig’s embrace as she describes it climbing up an oak. Douglas shows us, also, the prehistoric Glades people who developed their own civilization, in which art, craftsmanship and religion burgeoned and spread throughout the neighboring communities. Her descriptions are so vivid, it’s as though she was hiding behind a palmetto tree underneath her big floppy hat, peering at dancing priest who wore wood-carved animal masks, or watching a funeral ceremony in which the dead were buried in mounds with their knees to their breast, "the position he held," Douglas writes, "unborn, in oblivion of his mother's body.” Then Douglas carries us far from the palm-thatched houses in Indian villages to the bustling, sordid cities of Europe where men in harbors and quayside wine shops held their flat maps of the ocean, completely absorbed by the looping rings of the Outer Sea. Douglas evokes the discoverers’ perilous journeys to the New World, the dread of the lurking, frowzy pirates, and the devastation of the Indians by the white man. She writes, “The docile Arawaks of the first islands died like flies. The fiercer Caribs of Cuba were being hunted, brought in long chained files to the mines and the fields and exterminated. They died too rapidly, unable to bear the unremitting toil, the lash, the starvation, the overcrowding, the disease, but most of all slavery.” We can almost hear the hissing of the arrows coming out of the mangroves and see the stripe of war paint on a high cheekbone behind the blades of sawgrass. In the chapter “The Free People,” Douglas introduces us to the Seminoles, whose name in the Muskogee language means “people of distant fires.” We meet Tiger Tail and Billy Bowlegs, valiant heroes of the Glades, who resisted forced migration as well as the cajoling and bribes of men who wanted their land. Probably the most intrepid of all was young Osceola, who when forced to sign a treaty he knew the Americans would breach, walked up to signing table, pulled out his knife and stabbed it into the table through the paper. “This is how I sign.” he said. When Florida became a state, the legislature urged Congress to “examine and survey Everglades, with a view to their reclamation.” Men with large handlebar mustaches and schoolboy logic made out an impetuous plan to drain the Everglades with the goal of converting it to farmland. These men were the first to be responsible for creating a change that would be as drastic as the glacial melting nearly four thousand years before. Soon, the dredging began. The dynamiting began. Dikes and canals were constructed. Railroads ran like metallic stitches through the peninsula, and towns swarmed like the hives of wasps. Douglas’ “systematic scales” soon went awry. The cypress and oaks were hewn down and the ancient relics of the first Glades people were destroyed. Oil boats stirred up sediment, and rainfall drainage became confused and inadequate. The once gentle meandering Kissimmee River ceased to flow. Tourists invaded the Indian land, and old women with careworn faces and necks strung with beads watched as their children learned to accept coins. Their existence had become a spectacle. Species, from the microscopic world to those who soared just below the stratosphere, began to die rapidly. Douglas writes, “What had been a river of grass and sweetwater that had given meaning and life and uniqueness to this whole enormous geography through centuries in which man had no place here was made, in one chaotic gesture of greed and ignorance and folly, a river of fire.” She ends the book, however, with a tone of hope: “Perhaps even in this last hour, in a new relation of usefulness and beauty, the vast, magnificent, subtle and unique region of the Everglades may not be utterly lost.” As a young woman, Douglas moved from Massachusetts to Miami to work for her father’s paper, which would eventually become the Miami Herald. In addition to writing articles for the paper, Douglas also wrote fiction and poetry. All of this experience shows in The Everglades: River of Grass, in which storytelling, lyricism, nature description, and history combine in a work we would today call “creative non-fiction.” Douglas was not alone in her fervor. In the decades before Douglas’s book, a national park had been proposed by other advocates such as Charles Torrey Simpson, John Kunkel Small, May Mann Jennings, David Fairchild, and the fiery Ernest Coe who referred to the Everglades as the “great empire of solitude.” In 1947, the same year The Everglades: River of Grass was published, the Everglades National Park opened. President Truman formally dedicated the park with a passionate speech. “For conservation of the human spirit,” he said, “we need places such as the Everglades National Park.” But the area reserved for the park was only part of the system, and the damage continued. By 1974, the legendary wading birds had been reduced by 90 percent. Since 1984, the wood stork has been listed as a federal endangered species. The Florida panther, which once could be seen slinking behind cypress trees all over the Everglades, is now in immediate danger of extinction. Generations who have read Douglas have continued the struggle. In 1984, the Water Management District built steel walls across the Kissimmee to recreate the river bends so that water could be pushed back down towards the Everglades. Bureaucrats, scientist and tribal government leaders came together to discuss the restoration of the Everglades, and today projects continue—and continue to be debated. Until her death in 1998, Douglas remained eminently active in rousing support in saving the Everglades, and Friends of the Everglades, founded by Douglas in 1969, continues to work to guarantee that “her” river will never cease to flow again. Statewide, schoolchildren read Douglas’s classic, and remembering the history of the Everglades has become part of Florida’s ethical and social responsibility. Besides being a powerful work of literature, the book is also a colorful atlas of the past, which can serve as a guide for those who shape the Glades’ future. To look out into the panorama of the Everglades’ unbroken greenness is to rediscover the concept of infinity. Douglas writes, “The water is timeless, forever new and eternal.” Like the river she describes, Douglas’ voice is also immortal. Jennifer Hearn lives in Miami where she writes about nature and traveling. She would like to name her first born son Osceola. |

|

The Barefoot Mailman by Theodore Pratt

(Florida Classics Library, Paperback, pp.215, 50th Anniversary Edition, 1993, out-of-print but available online from $5.23) A Reconsideration by Gwen Keenan This replica of the original statue of the Barefoot Mailman stands at the foot of the Hillsboro Inlet Light. There the eleven barefoot mailmen crossed the hazardous inlet as they carried the mail along the beaches between Palm Beach and Miami. Speculation that one of them, James “Ed” Hamilton, who disappeared here in 1887, was attacked by alligators while swimming the inlet is the basis for a significant scene in The Barefoot Mailman. The original statue was erected in front of a Hillsboro restaurant and was later moved by the town to its present location, in front of the Hillsboro Beach Municipal Hall (1210 Hillsboro Mile, Hillsboro Beach, FL).

|

The Barefoot Mailman by Theodore Pratt

A Reconsideration by Gwen Keenan In stop-and-go, rush-hour traffic near Palm Beach, the idea of a three-day walk down the beach to Miami seems a plausible, desirable alternative mode of transit. This footloose fantasy comes from my recent rereading of the perennial Florida favorite The Barefoot Mailman by Theodore Pratt, first published in 1942 and set in the 1890s.Eighteen years ago I read The Barefoot Mailman, at the suggestion of my Floridian boyfriend, now husband, to get a feel for what Florida was. I’m from Ohio, and my vision of Florida revolved around sunny beaches, tall buildings and a famous, oversized rodent. This was my first introduction to “Cracker” living and the characters who settled this unlikely patch of brush and swamp. It set the hook that led me to Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Ernest Hemingway and a fuller, richer understanding of the state I now call home.

Mystery, intrigue and a compelling love interest make The Barefoot Mailman, a timeless, pleasant read. Pratt’s characters are eminently likeable, if vaudevillesque: good suitor, bad suitor, maiden, and a cast of colorful characters in support. Pratt constructs the rivalry of his two main male characters for the love interest so that it stands for the battle between competing interests for Florida itself. Steven Pierton, the barefoot protagonist, is an orphan raised by the bachelor Bethune Brothers in the frontier Palm Beach. Steven carries the southbound post three days down the beach, the only passable trail to Miami, overnights, and then returns with the northbound mail. Steven is the local boy made good, having secured this rare stable federal employment. He knows everyone and is known to them. Steven also guides newcomers to Miami, via his route. Enter Adie, a boarding school runaway, who “hitches a walk,” and goes on to play a pivotal role between the two male leads. Steven knows and appreciates the landscape, which he describes to Adie: And you don’t locate morning glory land like this all the time. I’m hoping to find one [a wife] who’ll plant herself here and grow and bloom just like they do. And who’ll like the birds and the other living things. Even the snakes when they can be friendly-like, such as a big old black snake who comes around the house to eat palmetto bugs and lizards and scorpions and keeping away rattlers and moccasins. You hear the birds? It’s them I’m wanting her to like most. Steven’s Eden here is Hypoluxo, an island now largely covered in condos and sandwiched between the concrete banks of high-rises to the east and the ten-lane I-95 that pulses to its west. In his words, there is a yearning to hold on to the harsh and fleeting natural beauty that was early Florida.

Steven’s second “passenger” is Sylvanus Hurley, the suave, unscrupulous land prospector. As they walk toward Miami, Sylvanus expounds on the promise of this beachfront. “I looked up the weather records before I came here. . . Climate’s the thing, that’s what I’m interested in. Take this beautiful sunny day with the blue sky and the breeze and the waving palm trees. . . This is the American Riviera. That’s what it’s going to be here, that’s what I’m going to make it. Steven retorts, “The land’s pretty good right here by the coast, but you go back about as far as you can spit and there you get it by the gallon instead of by the acre.”

This split between the unscrupulous, if ultimately visionary, developer and the contemplative, pastoral mailman haunts Florida to this day. Pratt skillfully uses the local trading posts to flesh out the contrasting hopes for fledgling Florida with each mail delivery: "Pineapples is the thing here. Citrus? Truck vegetables? Well, maybe. But let me tell you: ten thousand pineapple plants can be put on one acre of ground to return as much as two thousand dollars a year." That was straight Middle West twang, probably Illinois. Sylvanus seeks to snap up acreage and create a boom town based on the climate, while Steven expounds the natural beauty and parries Sylvanus’ underhanded efforts to corner the Miami land market. The ensuing contest for the hand of Miami’s most eligible and attractive maiden is an allegory for the competing loves which shaped old Florida and vie for its affections even now.

Author of thirty books – thirteen of which are set in Florida—Theodore Pratt knew the land. His prose captures the look and smell and feel of Cracker Florida: Before noon they came to Hillsborough. You could tell it from far away by the great trees its water nurtured. There were gray cypresses thicker than a barrel, lofty pines, and great banyans whose ropelike air roots dropped to the ground from high overhead… And Mailman gives us the bird song that serenaded these settlers:

They listened. There was the shrill call of the parakeet. A limpkin wailed insanely. Ground doves cooed sensuously, almost indecently. A woodpecker tapped. A chuck-will’s-widow whistled and another answered. Most of all there was the continuous message of a mockingbird, scolding between imitations of other calls. Perhaps these descriptions, which preserve that fleeting natural beauty and the rugged individuals who first settled here, provide the best recommendation. The book is more poignant to me now that I have seen so many wild places disappear and have witnessed the joy of my children as they experience the pure wild beauty that remains. Pratt’s The Barefoot Mailman is pedestrian-paced journey across sandy beaches, gator-infested inlets, and time, guiding us to an unforgettable and unforgiving land of beauty and possibility.

Gwen Keenan is a budding freelance writer and retired Coast Guard commander. She lives in Tallahassee with her husband and their four young children. |

|

The Corpse Had a Familiar Face by Edna Buchanan

(Pocket, Paperback, 448 pages, $7.99) A Reconsideration by Susan Jo Parsons |

The Corpse Had a Familiar Face by Edna Buchanan

A Reconsideration by Susan Jo Parsons In the late 70’s and early 1980’s Miami became the black sheep of the Florida family as it went from a sleepy vacation resort to a major center of crime. Some fled the influx of refugees and the violence surrounding the “cocaine cowboys,” but others were drawn to the fascinations of this city in transition. Edna Buchanan is one of those people.

In The Corpse Had a Familiar Face Buchanan chronicles this period. As a reporter on the police beat at The Miami Herald, Buchanan saw it all—and then some. The book is written in a reporter’s style, with short synopses of numerous crimes, longer features of others and chapter titles as simple and revealing as headlines. Buchanan also pauses to reflect along the way. “In my sixteen years at the Herald, I have reported more than five thousand violent deaths,” she writes. “Many of the corpses have had familiar faces: cops and killers, politicians and prostitutes, doctors and lawyers. Some were my friends.” In addition to the crimes, Buchanan tells her own story. She was the only child of a New Jersey divorcee and as a child she occasionally filled in for her mother on the night shift at a candle factory. At an early age, she developed an interest in crime and pored over the local newspaper crime section while her peers were still reading the comics. Eventually, she and her mom went to Miami Beach for a vacation and Buchanan realized this was her true home. They relocated. Buchanan earned her position at the Herald not with a fancy degree, but after years of pounding the pavement for a smaller newspaper. She had to work a little harder than her coworkers since there weren’t many female reporters on the police beat in the 1970’s. “A woman in my profession has to convince the cops to forget she’s a woman,” she reflects. “You want them to think of you as a confidante, a professional who will always be fair, or if nothing else, a piece of furniture they are so used to seeing they forget you are there.” Buchanan won them over, and became so successful she was eventually awarded a Pulitzer. She expresses admiration for the Miami cops, and writes about several local cops who she remembers as heroes. But she also remembers the cops who went bad. Other criminals she recalls in the book include Murph the Surf, an enigmatic Miami Beach jewel thief, Willie the Actor, a famous bank robber, and Robert Carr, a serial killer. She remembers the chaos the city faced when “the most ruthless killers ever encountered in Miami, arrived among the Mariel refugees. Some men who would have, should have, died in Cuban prisons or mental wards [opened] fire on strangers in crowded bars or cafeterias to prove quien es mas macho.” And she recalls the 1980 riot when “Life would never be the same again…Hearts would break…Eighteen men and women would die, and three hundred and fifty people, some of them children, would be hurt.” And this brings us to the heart of the book. Buchanan remembers the victims, long after others have forgotten. “The face of Miami changes so quickly,” she writes, “but the dead stay that way. I feel haunted by the restless souls of those whose killers walk free.” “A corpse has no privacy,” she explains, “…[homicide detectives have] a single mindedness matched only by that of a jealous lover, they must know all about you…Secrets you wouldn’t tell your best friend. Particulars you didn’t understand about yourself. Nothing is sacred…They will read your diary and your mail and scrutinize the contents of your safety deposit box and your stomach.” She still wonders about the unsolved crimes, and in the 2004 edition, she updated a few of the cases. In the twenty years since The Corpse Had a Familiar Face, Buchanan has written several novels including Cold Case Squad, and a popular mystery series about Britt Montero, a Miami reporter. Her most recent book in the series, Love Kills, was released in June. But The Corpse Had a Familiar Face is her classic book. It is a great history of crime in Miami and an inspirational story about a woman who realized she wasn’t just writing stories for a deadline, she was writing about people. Susan Jo Parsons is the founder and publisher of The Florida Book Review. |