FBR Feature: Tennessee Williams in Key West

"Do You Want to See My Shrine?"

By Madeleine Blais

By Madeleine Blais

The bus pulled out of the depot and glided past sunny streets filled with music about how you should not cry for me, Argentina. At least half the stores seemed to be selling suitcases. There was no doubt about it. Miami was a town on the go.

|

In 1979 Tropic Magazine of The Miami Herald (“Birthplace of Dave Barry”) was still an easy enough place to get freelance work and the editors there gave me an assignment to interview the playwright Tennessee Williams in Key West: the place where we run out of East Coast, where the cabs are pink, the sidewalks buckle, roosters roam free, people applaud the sunset, every local restaurant has the best fish sandwich in town, the t-shirts are vulgar, the cats have six toes, where in the early 90s Hooters went out of business because it was too Ohio, ceiling fans and balconies abound, the smell of beer competes with the smell of a new catch and the smell of night-blooming jasmine, and where sky and water are involved in some kind of sexy dance, blue on blue, and they let us watch.

If Key West was a dream, the opportunity to interview Tennessee Williams was a dream within a dream. I had wanted to meet him since the day I first heard an excerpt from The Glass Menagerie recited at a drama festival I attended in high school. I was stopped dead by the fantasy-besotted boy who wanted to write and to escape, the girl trapped in her fragility, the mother whose power at home came in part from being so powerless in the world. What floored me most was that a young girl’s collection of figurines on a shelf near the Victrola could be a plot device, a major source of action and metaphor. You mean you can write about that? To get to Key West, I traveled by bus the one hundred and fifty miles or so from Miami for the better part of a breezy February day. We passed fleet after fleet of charter fishing boats, with their promise of adventure and marlin. From time to time we would head over a series of baby bridges leading to villages the size of a twinkle, with shacks posing as stores, selling bait, booze and turtle soup. The trip, which normally takes three and a half hours, on average, due to narrow one-lane roads, took twice that because we stopped at every little bait shop and gas station along the way to pick up men traveling on their own, fair weather customers and drifters, many carrying their possessions stuffed inside green garbage bags, including, from what I could see, all the necessities: copies of behind-the-counter magazines, pint-sized bottles of sweet alcoholic beverages, and extra packs of cigarettes. Mostly they dozed off and were silent, or else they snored, or they bragged. |

“Almost one hundred proof.”

“That baby could go.”

“One fine woman . . .”

We passed Key Largo, with its billboards of smiling, sunlit people in bathing suits, wearing masks and snorkels as they explored reefs, and we passed the Last Chance Saloon, whose function was obvious, and another joint that said “Girls! Girls! Girls,” function also obvious.

I sat, prim and alert, directly behind the driver.

He was filled with bluster and unsolicited editorials.

My notebook came in handy that day:

“This is the thing about Florida,” he said. “We have all kinds in these parts.”

The point was not new.

You heard it all the time: It’s a real United Nations, especially the closer you get to Miami and Dade Country. There is old money, new money, drug money and no money. You have your White English, your Black English and your No English. Your cocaine cowboys, your out of work dictators, your rich housewives and the maids who are scheming to replace them, your former royalty, your big-time lawyers, your hot-shot docs, your exercise nuts, and your sun junkies.

This guy was singing the same tune, “Like I said, all kinds. But when you boil it down, at least in my experience, there are really only two kinds of people who live in Florida, those who can’t believe their luck and those who can’t wait for theirs to change.

“Just remember one thing. South Florida is more than just a pretty postcard. Some people say it is nothing but a big swamp with a lot of shopping centers plunked down on top. And the swamp part guarantees it is chock-full of dangerous creatures. I read a whole book about it. We have your blister beetles and your assassin bugs and your tarantulas and your scorpions, and that’s not even counting three kinds of rattle snakes, two kinds of coral snakes, not to mention your copperheads, your jellyfish, your Portuguese man-of-war, and your stingrays, and your alligators.

“Far as I’m concerned, it’s pure idiocy to leave the house if you’re not equipped with gauze bandages and Isopropyl alcohol and Betadine and Calamine lotion and Adolph’s meat tenderizer, unseasoned naturally, to rub on all those bug and snake induced wounds, not to mention tweezers and razor blades and surgical scissors. You just never know what you might run into.”

His words conflicted with the seeming good will of the landscape: the flatness that went on forever with its promise of easy living, the clean green feeling all around, all those palm trees, swaying in the breeze.

“And as if nature weren’t scary enough, we have another form of dangerous creature in these parts that will make you lose even more sleep. And who might that be? Well, just look around at your fellow passengers and you’ll see what I’m talking about. That most stealthy of predators, man himself. Read the headlines, sweetheart, if you don’t believe me. We have people in these parts that immure their brides in concrete walls. Kids who kill old ladies so they can steal their Pontiacs and go to Disneyworld and then blame it on their parents for not paying enough attention to them, blame it on television intoxication or some damn fool thing like that. Fellow, down in Hialeah, openly admitted to taking an ice pick and . . . well, better not to repeat it.”

I kept stealing glances at my fellow passengers, hoping that no one was listening to this joker and getting any bright ideas.

The Herald had given me a cash advance of one hundred and fifty dollars for transportation and to cover the cost of a room for up to three nights in an inexpensive guesthouse. Tennessee Williams had been in the news because while walking down Duval Street, the main tourist drag, at midnight, singing some kind of Protestant hymn, inebriated, he was mugged.

His house had been robbed, and vandalized.

Later his gardener was found slain—in his own apartment, not on Williams’s property, but the police made a disturbing discovery. Over the course of many years, this trusted employee had been stealing the outtakes from Tennessee William’s wastebasket, the prose that the writer deemed too faulty to keep, in the hope that it would be worth something some day. This was especially violating because most of it was substandard and Williams knew it; he had a legendary case of writer’s block.

Some teens—it was said to be local kids, this was before the days of spring breakers on their predictable benders—took to amusing themselves by lighting firecrackers and throwing beer cans up on the playwright’s porch and shouting, “Come on out, faggot.”

Yet he loved Key West, and had from the first time he visited, as evidenced by this letter written three years before The Glass Menagerie was staged:

“That baby could go.”

“One fine woman . . .”

We passed Key Largo, with its billboards of smiling, sunlit people in bathing suits, wearing masks and snorkels as they explored reefs, and we passed the Last Chance Saloon, whose function was obvious, and another joint that said “Girls! Girls! Girls,” function also obvious.

I sat, prim and alert, directly behind the driver.

He was filled with bluster and unsolicited editorials.

My notebook came in handy that day:

“This is the thing about Florida,” he said. “We have all kinds in these parts.”

The point was not new.

You heard it all the time: It’s a real United Nations, especially the closer you get to Miami and Dade Country. There is old money, new money, drug money and no money. You have your White English, your Black English and your No English. Your cocaine cowboys, your out of work dictators, your rich housewives and the maids who are scheming to replace them, your former royalty, your big-time lawyers, your hot-shot docs, your exercise nuts, and your sun junkies.

This guy was singing the same tune, “Like I said, all kinds. But when you boil it down, at least in my experience, there are really only two kinds of people who live in Florida, those who can’t believe their luck and those who can’t wait for theirs to change.

“Just remember one thing. South Florida is more than just a pretty postcard. Some people say it is nothing but a big swamp with a lot of shopping centers plunked down on top. And the swamp part guarantees it is chock-full of dangerous creatures. I read a whole book about it. We have your blister beetles and your assassin bugs and your tarantulas and your scorpions, and that’s not even counting three kinds of rattle snakes, two kinds of coral snakes, not to mention your copperheads, your jellyfish, your Portuguese man-of-war, and your stingrays, and your alligators.

“Far as I’m concerned, it’s pure idiocy to leave the house if you’re not equipped with gauze bandages and Isopropyl alcohol and Betadine and Calamine lotion and Adolph’s meat tenderizer, unseasoned naturally, to rub on all those bug and snake induced wounds, not to mention tweezers and razor blades and surgical scissors. You just never know what you might run into.”

His words conflicted with the seeming good will of the landscape: the flatness that went on forever with its promise of easy living, the clean green feeling all around, all those palm trees, swaying in the breeze.

“And as if nature weren’t scary enough, we have another form of dangerous creature in these parts that will make you lose even more sleep. And who might that be? Well, just look around at your fellow passengers and you’ll see what I’m talking about. That most stealthy of predators, man himself. Read the headlines, sweetheart, if you don’t believe me. We have people in these parts that immure their brides in concrete walls. Kids who kill old ladies so they can steal their Pontiacs and go to Disneyworld and then blame it on their parents for not paying enough attention to them, blame it on television intoxication or some damn fool thing like that. Fellow, down in Hialeah, openly admitted to taking an ice pick and . . . well, better not to repeat it.”

I kept stealing glances at my fellow passengers, hoping that no one was listening to this joker and getting any bright ideas.

The Herald had given me a cash advance of one hundred and fifty dollars for transportation and to cover the cost of a room for up to three nights in an inexpensive guesthouse. Tennessee Williams had been in the news because while walking down Duval Street, the main tourist drag, at midnight, singing some kind of Protestant hymn, inebriated, he was mugged.

His house had been robbed, and vandalized.

Later his gardener was found slain—in his own apartment, not on Williams’s property, but the police made a disturbing discovery. Over the course of many years, this trusted employee had been stealing the outtakes from Tennessee William’s wastebasket, the prose that the writer deemed too faulty to keep, in the hope that it would be worth something some day. This was especially violating because most of it was substandard and Williams knew it; he had a legendary case of writer’s block.

Some teens—it was said to be local kids, this was before the days of spring breakers on their predictable benders—took to amusing themselves by lighting firecrackers and throwing beer cans up on the playwright’s porch and shouting, “Come on out, faggot.”

Yet he loved Key West, and had from the first time he visited, as evidenced by this letter written three years before The Glass Menagerie was staged:

This is the most fantastic place that I have been yet in America. It is even more colorful than Frisco, New Orleans or Santa Fe. There are comparatively few tourists and the town is the real stuff. It still belongs to the natives who are known as ‘conks.’ Sponge and deep sea fishing are the main occupations and the houses are mostly clapboard shanties which have weathered gray nets drying on the front porches and great flaming bushes of poinsettia in the yards. This is beginning to sound like very bad travel literature—but I do wish you were here. I am occupying the old servant’s quarters in back of this 90-year old house. It has been converted into an attractive living space with a shower. The rent is $7 a week. I shan’t do anything the next few weeks but swim and lie on the beach until I feel human again. Then I shall learn how to fish. A good fisherman can thumb his nose at all commercial enterprise in the world.

I arrived late in the day, in time for sunset, which in Key West is a full-blown celebration held at Mallory Dock, where crowds gather to watch street entertainers compete with nature for their attention, the cat man and sword swallowers and the fire eaters and the guys who juggle knives.

|

My appointment with Williams was scheduled for the next day at noon. I woke up early and took a practice walk to his house so I could time myself and make certain I did not arrive late: forty five minutes each way. Then I backtracked and explored as much of the section known as Old Town as fully as I could, walking up and down those lopsided, crumbling sidewalks and those flat, low-lying, sea level, sun-washed streets, strewn with dead geckoes and little brown leaves and rotting mangoes, up and down and back and forth. I was propelled by smells, the coffee at the open air laundromat and the smell of fish, leading to a wonderland of docks with boats: Afternoon Delight, Water Cowboy, and Shore Enuf. I saw plenty of men dressed as women, flashing painted nails and tottering about on platform shoes in impossibly tight dresses. I went to the Southernmost Point and I walked by the museum dedicated to wreckers, people who would go out on the water and grab the goodies from boats that had gone aground nearby: swords from Spain, diamonds from

|

Africa, tea sets from China. At the Aquarium you could pet an actual shark. In Bahama Village, roosters with their stern secretarial air darted about as they hunted and pecked crumbs of food. The high school had a banner urging a team to victory, “Go Fighting Conch.” I felt sorry then and still do for any team with the misfortune of being called conch. It tastes terrible, like pencil erasers, chewy but dull, and it looks like erasers too, tough and pink. I am obliged to report that conch is one of the world’s great food disappointments.All around me, tourists flashed their wallets, hoping perhaps that the happiness that eluded them back home would overtake them on vacation. When it didn’t, they found solace in the usual false gods of trinkets and rum and burn marks from too much sun. I went by the house of a poet, Elizabeth Bishop, who said Florida was the state with the prettiest name. I saw the house where Ernest Hemingway lived, surrounded by a big fence he had built to discourage sightseers. Key West seemed to like him best of all: everything was Papa this and Papa that and there was even an annual contest to see who looked the most like him. Finally, at eleven fifteen, I set forth and found myself outside of the house of the playwright who wrote Streetcar Named Desire, featuring Blanche DuBois, who always depended on the kindness of strangers.

I knocked.

I paused.

I knocked again.

Inside, commotion: the sound of a vacuum cleaner.

More knocking.

At last, the door opened, revealing a young man who identified himself as a houseguest. He said the writer was not home and allowed as how Mr. Williams often forgets appointments, and he was at this very moment off having lunch. I don’t know if he suggested it or if I offered to come back at three o’clock in the hope of catching up with him then, but I do know I walked back to the guest house, and at two fifteen I set forth in the now woolly tropical heat.

This time the playwright was home, but indisposed, said his housekeeper, with something of a wink.

“Recovering from lunch, be my guess,” she whispered.

I went back again to my guesthouse that was now feeling less and less like a fey tropical getaway and more and more like a prison, and summoned my memory of the initial phone call.

“Sure, baby, come on down sometime. Monday would be just fine,” and maybe I heard only what I wanted to hear, a definite yes, instead of a friendly sure, sometime.

Were his words jumbled? Had his speech been slurred?

At five fifteen I set forth again and I arrived discombobulated and out of sorts at Williams’s house at six p.m. The burden of my debt to the Herald and the shame of coming back without a story weighed heavily in these considerations.

When he answered the door, Williams was in a similar state of dishevelment, of that kind of slight disintegration that occurs after the camera clicks when everyone has stopped posing. He was sixty-eight years old, the prime of his writing career was long gone, and he had the air of an aging lion. The TV was on. Cronkite. The news. Williams had just gone swimming and he was dressed in his trunks and a bathrobe. The stories on the TV were of devastation everywhere. He said that what worried him most in his life was not being mugged, not having someone pilfer his work, not the ignorant kids with nothing better to do than to heckle him, but that he could watch one awful news item after another and feel so indifferent. On the table were several empty gallon jugs of Gallo wine.

I would say he had momentarily forgotten about our appointment except I think the truth was even starker: he clearly had no memory of ever having made it.

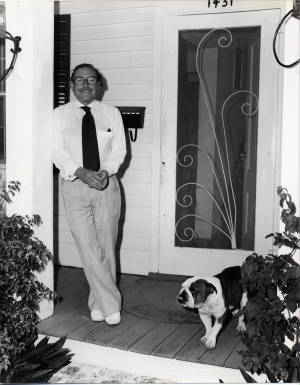

Yet Williams was a Southern gentleman and perhaps he sensed my panic as well as the pathos of my circumstances—the usual reporter’s stance, hat in hand, begging for a hand-out in the form of an apt quote or a memorable scene—for he proved to be cordial and rather than send me away he allowed me to spend portions of the next three days with him and his entourage, not even flinching when The Miami Herald sent a photographer down as well. Maybe he even found a certain theatre of redemption in my neediness and his benevolence. “Girl with notebook washes ashore; elderly man extends safety rope.”

I knocked.

I paused.

I knocked again.

Inside, commotion: the sound of a vacuum cleaner.

More knocking.

At last, the door opened, revealing a young man who identified himself as a houseguest. He said the writer was not home and allowed as how Mr. Williams often forgets appointments, and he was at this very moment off having lunch. I don’t know if he suggested it or if I offered to come back at three o’clock in the hope of catching up with him then, but I do know I walked back to the guest house, and at two fifteen I set forth in the now woolly tropical heat.

This time the playwright was home, but indisposed, said his housekeeper, with something of a wink.

“Recovering from lunch, be my guess,” she whispered.

I went back again to my guesthouse that was now feeling less and less like a fey tropical getaway and more and more like a prison, and summoned my memory of the initial phone call.

“Sure, baby, come on down sometime. Monday would be just fine,” and maybe I heard only what I wanted to hear, a definite yes, instead of a friendly sure, sometime.

Were his words jumbled? Had his speech been slurred?

At five fifteen I set forth again and I arrived discombobulated and out of sorts at Williams’s house at six p.m. The burden of my debt to the Herald and the shame of coming back without a story weighed heavily in these considerations.

When he answered the door, Williams was in a similar state of dishevelment, of that kind of slight disintegration that occurs after the camera clicks when everyone has stopped posing. He was sixty-eight years old, the prime of his writing career was long gone, and he had the air of an aging lion. The TV was on. Cronkite. The news. Williams had just gone swimming and he was dressed in his trunks and a bathrobe. The stories on the TV were of devastation everywhere. He said that what worried him most in his life was not being mugged, not having someone pilfer his work, not the ignorant kids with nothing better to do than to heckle him, but that he could watch one awful news item after another and feel so indifferent. On the table were several empty gallon jugs of Gallo wine.

I would say he had momentarily forgotten about our appointment except I think the truth was even starker: he clearly had no memory of ever having made it.

Yet Williams was a Southern gentleman and perhaps he sensed my panic as well as the pathos of my circumstances—the usual reporter’s stance, hat in hand, begging for a hand-out in the form of an apt quote or a memorable scene—for he proved to be cordial and rather than send me away he allowed me to spend portions of the next three days with him and his entourage, not even flinching when The Miami Herald sent a photographer down as well. Maybe he even found a certain theatre of redemption in my neediness and his benevolence. “Girl with notebook washes ashore; elderly man extends safety rope.”

|

The series of interviews over the course of

several days with Williams proved to be an interlude of grace and

incandescence, one of those pivotal moments

which is clearly pivotal even when it is happening.

He talked about loving dawn on Key West, daytime’s “great triumph over night.” Sometimes he would sit at his desk early in the day and drink a Bloody Mary to overcome what he called the “initial timidity.” He talked about how his mother was ninety four years old and how she thought there was a horse in her living room and how that pleased him because he knew she had wanted a horse as a child. “Longevity,” he told me, “is a family disease.” He said his mother never fully grasped how much of the character Amanda had been based on her. He refused to answer the phone in Key West because he feared it might be his brother, saying she had died. He also refused to inflate the meaning of the recent series of mishaps on the island, saying it was “ridiculous” to make a big deal about it: “There is violence everywhere.” He dismissed the rumors that he was going to sell his house and move away: “I am not in the habit of retreat.” |

“I used to be kind, gentle. Now I hear terrible things, and I don’t care. Oh, objectively, I care, but I can’t feel anything. Here’s a story. I was in California recently and a friend of mine had a stroke. He is paralyzed on the right side and on the left side and he has brain cancer. Someone asked me how he was doing and I explained all this and the person said, ‘But otherwise is he all right?’ I said, ‘What do you want? A coroner’s report?’ I never used to react harshly, but I feel continually assaulted by tragedy. I can’t go past the fact of the tragedy; I cannot comprehend these things emotionally. I cannot understand my friend who is sick in California and who loved life so much he is willing to live it on any terms.

“Sometimes I dream about getting away from things, recovering myself from the continual shocks. People are dying all around you and I feel almost anesthetized, feel like a zombie. I fear an induration, and the heart is, after all, part of your instrument as a writer. If your heart fails you, you begin to write cynically, harshly. I would like to get away to some quiet place with some nice person and recover my goodness. I cannot, for instance, feel anything about my mother. I dream about her, but I can’t feel anything.

“I would like to invite my sister, Rose, down to Key West for a visit. I was in psychoanalysis once for about nine months, and the psychiatrist told me to quit writing and to break up with someone. I did neither, but the one thing analysis showed me was that my father was a victim, too, and mother was the strong one. She is the one who approved the lobotomy. My sister had been away at a school for girls, All Saints School, and when she came home she talked about how the girls stole candles from the chapel and committed self-abuse. My mother wanted her to stop saying those things, just like Mrs. Venable in Suddenly, Last Summer. My mother could not bear the idea of anything sexual. Every time she had sexual intercourse with my father she would scream. Rose and I would hear her and we would run out of the house, screaming, off to a neighbor’s. My mother had three children, so I imagine she was raped rather frequently.”

Just as we were winding down, he asked me if I wanted to see his shrine to St. Jude.

He then ushered the photographer and me into a side room with an alcove featuring a table with a white cloth. It had a picture of his sister Rose, whose bad thoughts had been amputated, and it had a Tree of Life, some votives, and a veiled Madonna. When the rose bushes were in bloom, it always had fresh flowers. A self-portrait of Williams’s dead lover, Frank Merlo, hung on the wall nearby.

From the Herald story:

“Sometimes I dream about getting away from things, recovering myself from the continual shocks. People are dying all around you and I feel almost anesthetized, feel like a zombie. I fear an induration, and the heart is, after all, part of your instrument as a writer. If your heart fails you, you begin to write cynically, harshly. I would like to get away to some quiet place with some nice person and recover my goodness. I cannot, for instance, feel anything about my mother. I dream about her, but I can’t feel anything.

“I would like to invite my sister, Rose, down to Key West for a visit. I was in psychoanalysis once for about nine months, and the psychiatrist told me to quit writing and to break up with someone. I did neither, but the one thing analysis showed me was that my father was a victim, too, and mother was the strong one. She is the one who approved the lobotomy. My sister had been away at a school for girls, All Saints School, and when she came home she talked about how the girls stole candles from the chapel and committed self-abuse. My mother wanted her to stop saying those things, just like Mrs. Venable in Suddenly, Last Summer. My mother could not bear the idea of anything sexual. Every time she had sexual intercourse with my father she would scream. Rose and I would hear her and we would run out of the house, screaming, off to a neighbor’s. My mother had three children, so I imagine she was raped rather frequently.”

Just as we were winding down, he asked me if I wanted to see his shrine to St. Jude.

He then ushered the photographer and me into a side room with an alcove featuring a table with a white cloth. It had a picture of his sister Rose, whose bad thoughts had been amputated, and it had a Tree of Life, some votives, and a veiled Madonna. When the rose bushes were in bloom, it always had fresh flowers. A self-portrait of Williams’s dead lover, Frank Merlo, hung on the wall nearby.

From the Herald story:

The photographer took a picture of Williams, who had fallen silent. Wearing only his robe, he recalled the playwright’s own words from The Night of the Iguana: “When the Mexican painter Siqueiros did his portrait of the American poet Hart Crane, he had to paint him with his eyes closed because he couldn’t paint him with his eyes open—there was too much suffering in them and he couldn’t paint it.” As Williams sat next to the shrine and the portrait of his dead lover, there was a nakedness to him, except for one detail. He wore sunglasses in the dim room, as if to reveal his eyes, particularly during this, the final scene before we left, would be to reveal too much, to demand too little of his audience. Miss Rose had been punished for her madness, diagnosed as lunacy. He had been honored for his, hailed as genius.

Had he escaped?

“Oh, no,” he said, in his cadenced voice, “I have been punished, too, by her punishment, and by difficulties of my own.”

As a reporter for The Miami Herald, Madeleine Blais won a Pulitzer Prize. She is the author of In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle (one of Sports Illustrated's 100 best sports books of all time), The Heart is an Instrument: Profiles in Journalism, and the memoir Uphill Walkers. Read more about her here.

This essay also appeared in the Jan. 18, 2008 edition of Solares Hill, Key West's oldest weekly newspaper.