Florida Politics

On this page:

◇ The Reluctant Republican by Barbara Olschner, reviewed by Dawn S. Davies

◇ Walkin' Lawton by John Dos Passos Coggin, reviewed by Bob Morison

◇ Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary by James C. Clark, reviewed by James Elens

◇ From Yellow Dog Democrats to Red State Republicans: Florida and Its Politics since 1940 by David R. Colburn, reviewed by Lynne Barrett

◇ An interview with Richard Grayson, author of Write-In: Diary of a Congressional Candidate in Florida's Fourth Congressional District with FBR correspondent Tom DeMarchi

◇ The Reluctant Republican by Barbara Olschner, reviewed by Dawn S. Davies

◇ Walkin' Lawton by John Dos Passos Coggin, reviewed by Bob Morison

◇ Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary by James C. Clark, reviewed by James Elens

◇ From Yellow Dog Democrats to Red State Republicans: Florida and Its Politics since 1940 by David R. Colburn, reviewed by Lynne Barrett

◇ An interview with Richard Grayson, author of Write-In: Diary of a Congressional Candidate in Florida's Fourth Congressional District with FBR correspondent Tom DeMarchi

|

The Reluctant Republican by Barbara Olschner

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 142 pp., $24.95) Reviewed by Dawn S. Davies |

The Reluctant Republican

Reviewed by Dawn S. Davies The Reluctant Republican by Barbara Olschner is an intriguing kiss-and-tell account of Olschner’s 2010 congressional run as a moderate Republican in the Florida Panhandle during the height of a conservative swing within the party. Not only does she lose the primary, she comes in last place, as Olschner admits at the beginning of the story, so the election itself holds no suspense. This is not a story about losing an election. Olschner’s Congressional District 2 is 34% registered Republicans, and among them are the state’s most socially conservative Republicans. A simpleton could predict that Olschner,as a moderate Republican with no political experience, would be headed for a pummeling before she even stepped into the ring. Let me say it again, this is not a story about losing an election. It is a story about an idealistic, yet reasonable person who finds herself immersed in the smarmy, sleight-of-hand world of politics. As a recovering Democrat who became a Republican, and who now attends PAA (Political Aficionados Anonymous) meetings to recover from my Republicanism, this book helped me remember why I do not agree with a two-party system that selects for ideologue candidates who move down the campaign trail like wooden puppets armed with bullet points. This particular system leaves Olschner, a self-proclaimed pragmatist and a fiscal Republican, without a place to hang her hat. The Dems don’t want her—she’s too conservative—and besides that, with her belief in less taxation, individual responsibility, and limited government, she truly is a Republican. The problem is that the Republicans don’t find her conservative enough, and her pesky use of the law and knowledge of the Constitution appear to blow holes through some of their ideology. By Olschner’s account, during the height of an uber-conservative swing, refusing to toe the party line causes her to be seen as an afterthought, the barely-tolerated pretty gal who thinks she can play with the big boys. During a meeting with RNCC chairman Representative Pete Sessions, he hands her his personal cell phone number and tells her to “call him before she does anything stupid.” Olschner’s interaction with the other candidates is the most delicious part of the kiss-and-tell. Much of the dialogue is alarmingly ridiculous and often funny. If her account is true, this congressional election veers into the comedic early, beginning with the only other female candidate who makes a habit of calling Olschner late at night, after seemingly “sucking down white wine with a straw,” reminding Olschner of the many ways she will not be successful in the race. During the Destin debate in July of 2010, candidate Steve Southerland, in referencing the Constitution, quotes the Declaration of Independence, and at some point during the evening, relatives of other candidates, and in one instance, a candidate himself, tell Olschner they would be willing to support her. On a serious note, Olschner’s account of the debates illuminates her belief that “one of the glaring problems with the current Republican Party is the support and encouragement for candidates and leaders who use belief systems and agendas—rather than objective knowledge—to make decisions.” She learns that being reasonable has very little to do with being successful in politics. Olschner admits that she “thought that average voter, like the average juror, would respond to reason and logic.” As a trial attorney she should have understood more about the balance of rhetorical devices as they relate to political responsiveness and voters. Most of the candidates rely on the appeal to pathos to sway their voters’ emotions, rather than knowledge and reason. As she says, “political problems often evoke responses more visceral than rational.” Olschner falls for the sophomoric idea that all people really need is a candidate who tells the truth. She believes that logic and reason should prevail in every situation, when in the real world of political elections it does nothing of the sort. Politicians are not only trained, they are indoctrinated, often while in college, and they learn early how to evade questions, think strategically, and play the game. The sport of politics is an underhanded, back-alley one with unwritten rules that can leave a new player with bloody teeth. Olschner writes, “I was so out of step with the right wing of the party that I became a mere spectator to what amounted to a vulgar brawl.” Olschner is an attorney who made an unsuccessful foray into politics, then wrote a book about it. All political books have agendas. This one didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already suspect about Florida politics, but it is a good story that serves a purpose, and in her heart, the author holds true to the essence of what her party is supposed to stand for and reminds us that any party, left or right, that is dominated by a single, narrowly defined ideology or agenda is not good for our country. I applaud Olschner for writing a story worth reading. Dawn S. Davies was raised in Fort Lauderdale. She is the recipient of the 2013 Betty Gabehart prize for nonfiction, and has been published in Real South Magazine. She is the graduate coordinator of the F.I.U. Writers on the Bay Reading Series and the assistant fiction editor for Gulf Stream Magazine. |

|

Walkin' Lawton by John Dos Passos Coggin

(Florida History Press, Paperback, 513 pp., $24.95) Reviewed by Bob Morison |

Walkin' Lawton

Reviewed by Bob Morison Lawton Chiles was a little-known-outside-Tallahassee state representative when he literally walked his way into the U.S. Senate in the 1970 election. He covered over 1,000 miles on foot from the Panhandle to the Keys, introducing himself to Florida and much of Florida to himself. (His campaign, operating on shoestring, managed to afford five pairs of boots.) Eighteen years later, and frustrated with the backroom ways of Washington, he retired from the Senate and not long thereafter got the job he really wanted – governor of Florida. After two terms, and within weeks of retiring, he passed away in the Governor’s mansion “with his boots on.” John Dos Passos Coggin takes us every step of the way in Chiles’ career. Schooled at the University of Florida and working as a small-town lawyer, young Lawton was treading a predictable career path when he ventured into politics and won the first of many elections against far-better-financed opponents. He won the state legislature seat in part because he took the unusual step of campaigning in the predominantly Black sections of Polk County. Chiles was unknown in most of Florida and predicted to be an also-ran in the Democratic primary for the Senate nomination when “The Walk” put him on the map. Along the way, people and local media became curious about the candidate, and he became more concerned about the issues Floridians faced, from taxation to the exploitation of migrant workers to the Vietnam War. He was still polling low when he reached Miami and a street corner “honk and wave” campaign lifted his spirits and his chances. The walk was an exercise in meeting people and listening to what they had to say. He connected with people because he treated no one as ordinary. In Washington, as in Tallahassee, he worked closely with like-minded colleagues (former Sen. Sam Nunn of Georgia wrote the introduction to Walkin’ Lawton), but he butted heads with the power structure. In both places, he fought for political reform and governmental transparency through “sunshine” laws. Early in his career he took up what became permanent causes: education, housing, health care, equal rights, reducing poverty, senior citizen services. Pre-natal and infant care became a focus when his grandson, Lawton IV, was born prematurely. As Governor, Chiles enjoyed controlling the agenda, but it wasn’t always a popular one. You couldn’t tell his party from his positions, as he worked for deficit reduction, tax reform, simplifying regulations, ethics reform, and campaign finance reform. Chiles never accepted large donations and so was never beholden to special interests. He never really took on Big Sugar, but he engineered Florida’s landmark financial settlement from Big Tobacco. He took the most heat for vetoing a law authorizing school prayer. Coggin shows us the inner Chiles through the recollections of others. He was family man, devout Christian, practical joker, hunter, loner. He was restless. He was loyal to a fault. He suffered bouts of clinical depression. We also meet Chiles through his own sometimes cryptic expressions. “Let that ox stay in the ditch.” “The cat’s on the roof.” And we see how Chiles defined himself in contrast with his political opponents. During the general election campaign for the Senate seat, the Republican held a $1,000 a couple cocktail party featuring Attorney General John Mitchell. The Chiles campaign set up camp a few miles away, hired some country music, and gave away 1,576 boxes of chicken. Chiles wrote very little aside from everyday notes to colleagues. Coggin tells the story with the help of news accounts and over 100 interviews with family and friends (political enemies are under-represented). The book seems a labor of love – perhaps too much love. Every action is worthy, every setback a valiant effort. Coggin praises Chiles for getting the Federal government in gear when the initial response to the devastation of Hurricane Andrew was slow and inadequate. Those of us in Miami at the time recall weatherman Brian Norcross having to first get Lawton Chiles in gear. Chiles himself would find the pedestal he’s put on a bit uncomfortable. Chiles’ one lengthy opus was his diary of published “progress reports” during The Walk, which is included as an appendix. It reveals mental as well as physical progress. Early entries are daily and full of detail about places stopped, people met, things discussed, food eaten, and the condition of his feet. Later ones cover more time and territory, and include much more musing on campaign tactics and public policy. Walkin’ Lawton includes a gallery of 40 photos, an appendix with four Chiles family recipes, a bibliography, and 888 footnotes, but no index (which would have helped given the large cast of characters). Cutting is difficult when you like your subject, but the book would be better if shorter. The topic changes abruptly in some places, the reader is left hanging in others (what happened to Lawton IV?), and the book doesn’t quite live up to its billing in the Preface. But if you’re a fan of Lawton Chiles, or interested in Florida politics, or curious about how to gain political office on a shoestring, you’ll enjoy your stroll through Walkin’ Lawton. Bob Morison is co-author of Workforce Crisis and Analytics at Work. He lives in Miami. More info at his website. |

|

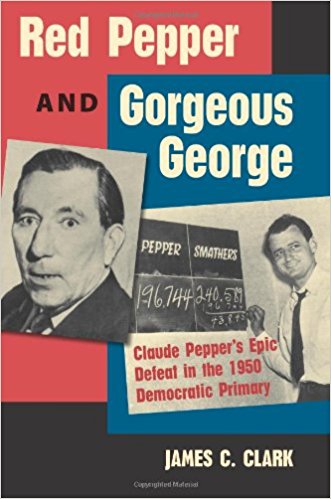

Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary by James C. Clark

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 197 pp., $29.95) Reviewed by James Elens |

Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper's Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary

Reviewed by James Elens It was long considered impossible to defeat an incumbent senator in Florida. For its entire first century of statehood, Florida had never once seen a challenger defeat a sitting U.S. senator in a primary, and since the Democratic stranglehold on the state rendered a Republican challenge hopeless, the Democratic primary was the only election that mattered. But why even have the primaries? Being a U.S. senator from Florida seemed like a lifetime appointment. Then in 1950, the right-leaning “Gorgeous George” Smathers’ pulled a stunning upset of the powerful Claude “Red” Pepper to cap off one of the most memorable elections the south has ever seen. Taking advantage of a shifting political climate and rising anticommunist fervor, Smathers launched a vicious attack campaign that stunned the party leadership at the state and federal levels, and which signaled the beginning a dramatic right-ward shift in southern politics. This important chapter of Florida’s history is documented in vivid detail in James C. Clark’s book Red Pepper and Gorgeous George: Claude Pepper’s Epic Defeat in the 1950 Democratic Primary. Clark employs crisp, clear prose and an ability to tie together many historical strands in order to construct his engaging nonfiction narrative. And he knows that in order to fully convey the significance of Smathers’ upset, it is necessary to paint a picture of Florida politics up to that time. The book does not intend to lure the reader with suspense. Indeed, the first sentence of the book reads, “As the election returns began to come in on May 5 in 1950, Claude Pepper learned early that he would not be returning to the United States Senate.” From there it plunges into the election’s fascinating set-up. The book spends the majority of its length detailing the state’s political history and the storied career of Claude “Red” Pepper, a fixture in the U.S. Senate and one of the most prominent New Deal Democrats. Clark depicts Pepper as a savvy politician, and writes of a 1928 state House campaign in rural Taylor County in which Pepper defeated incumbent W.T. Hendry by attacking his failure to vote on a bill that required farmer to dip their cows to remove ticks. But Pepper made this attack without getting entangled in the issue. Pepper never took a stand on the bill but was able to appeal to both supporters and opponents of the legislation merely by saying that the voters needed someone to vote on important issues. He upset Hendry and, as a result of his election, was named to the State Democratic Executive Committee. Pepper rose all the way to the U.S. Senate, but his shrewd maneuvering up the southern Democratic ranks would ultimately not protect him from the winds of political and cultural change that swept across American after the Second World War. Pepper never got along with his peers in Washington, including President Harry Truman, who found it hard to hide his dislike of the Sunshine State senator. Pepper had also been an outspoken advocate of good relations with the Soviet Union, and as Clark describes in tight and well-researched historical detail, the tide of anticommunist sentiment after the war made the senator extremely vulnerable as he continued to lose allies in Congress. Enter “Gorgeous George” Smathers in 1950, a conservative-leaning Florida Democrat who seemed to be Pepper’s antithesis. Smathers was so handsome that his political opponents tried unsuccessfully to dismiss him as a pretty boy. Where Smathers was agile and athletic, Pepper was awkward. Smathers stood ramrod straight, while Pepper seemed perpetually slumped over. Smathers was born to a wealthy family, while Pepper’s family always flirted with financial disaster. Smathers got attention naturally, while Pepper seemed to have to seize center stage. While Pepper was unpopular in Congress, Smathers was well liked. The two made for an extremely disparate pair of candidates, especially for a primary election. As described, their face-off seems like a dry-run for future television-age elections, notably John F. Kennedy’s defeat of Richard Nixon in 1960. But the most important difference Smathers tapped into was the candidates’ differing views on communism. Pepper maintained his stance of getting along with Russians and communists within America’s borders, and Smathers viciously attacked him for it, painting the incumbent as a communist sympathizer. Smather’s attacks were so intense that Pepper swore never to speak to the man again. Smathers went after Pepper on matters of civil rights too, pledging to oppose the kinds of progressive bills that Harry Truman was already trying to push through Congress. As Clark recounts them, these political attacks were frank, brutal, and public in a way the southern electorate had not seen before. And it all worked. Smathers defeated Pepper in the primary to the shock the Democratic establishment. Party leaders were nervous that the first defeat of a sitting Florida senator came at the hands of a fearless newcomer who leaned very far to the right. And they were right to worry. Though not a Republican victory, the results in the election signaled a momentous shift in southern politics, and over the next few decades conservative Republicans would wrest the region away from the party that had dominated it since the Civil War. The South would ultimately become dominated by Republican politics, though Florida remains a hotly-contested battleground state marked by controversial campaigns that recall the intensity of the Pepper-Smathers primary. The 1950 primary’s resonance as a watershed moment in American political history lies at the heart of Clark’s entertaining book. Clark, a history professor at the University of Central Florida, makes sure to drive the importance of this event home throughout his account, and thus the book is an important piece of reading for those fascinated by not only Florida politics but national political history as well. It’s a well-told tale of a handsome young challenger who rode the wings of cultural change (and a merciless campaign) and defeated a sitting senator where it had never been done before. A child of the beach, James Elens grew up in the Panhandle and now lives and writes in South Florida. |

|

From Yellow Dog Democrats to Red State Republicans: Florida and Its Politics Since 1940 by David R. Colburn

(University Press of Florida, Hardcover, 272 pp. $29.95) Reviewed by Lynne Barrett |

From Yellow Dog Democrats to Red State Republicans: Florida and Its Politics Since 1940

Reviewed by Lynne Barrett The reader of this book soon thinks of Florida as a map of conflicts, some open, some patched over till their uneasy alliance attains power and then splits apart. For fifty years, Republicans from the Midwest moved into Southwest Florida, and established a sort of Cincinnati-on-the-Gulf in an otherwise Democrat-dominated state. When the Yellow Dog Democrats (those willing, that is, to vote for a “yellow dog” if he was a Democrat) of North Florida turned Blue Dog Democrats (defined here as former Yellow Dog Democrats who choke “blue” on national Democratic party stands on civil rights and social issues) started voting Republican, too, the joined-up groups could prevail. But when it came time to govern (as in, say, the administration of Republican Bob Martinez in the late 80s) the rural, hard-scrabble Panhandle Blue Dogs and the business interests in the state split over Martinez’ advocacy of a tax on services. So things fell apart for Martinez, as Lawton Chiles (ex-Senator, folk-hero) ran for office, pulling the North Floridians back across the Democratic line, rejoining them with the more liberal Democrats in the Southeast part of the state—temporarily. David R. Colburn concentrates on Florida governors in his narrative. Gubernatorial elections put the factions on display, and whoever wins is then tested by the difficulty of getting anything done in a state with a fiercely defended, not very rich tax structure and what look like irreconcilable social and economic differences. A state, too, in which legislative districting has been a game played ruthlessly. The state legislature delayed throughout the 1950s doing constitutionally mandated redistricting per the 1950 census to avoid giving to South Florida and West Florida the representation they should have had because of the many who had moved there after World War II. In the mid 1990s, Republicans struck a deal with African-American Democrats to craft some oddly shaped districts with large African-American populations, allowing more black politicians to hold state office (a deal the white Democrats were unwilling to give them), but also thereby constructing lots of majority conservative, Republican districts, with almost no spot left where an election would be a real contest. In either set-up, a governor faces a legislature owing nothing to him. Something I have watched but never understood before reading this book is the ordeal of a Florida gubernatorial campaign. In both parties, multiple contenders run, each, usually, from a different geographical base, that very strength in one spot causing them to be suspect or resented at the state’s opposite extremes. They scrap and fight, through an elimination contest which often includes not just a primary but a run-off, too. This can leave the victor damaged and exhausted, too weak to prevail in the general election, or, if he does make it, too saddled with ill-will to govern. This system was developed in the years when the Democrats had a monopoly in the state, so that the Dem. nomination made the governorship a done deal, but as the Republicans grew in numbers, they adopted the same trial by fire. (Recently-arrived Floridians will have seen this during the election of 2006 which offered plenty of nasty infighting, augmented by Jeb Bush’s attempt to settle some scores on his way out of power.) The size and divisions in the state requires large personalities—people who can do well on television, and, interestingly, who know who they are and do not waver—to get elected with any hope of success thereafter. A fascinating pattern Colburn describes is that it has often been better to come in second in the first round of the primary and then amass the following of the others eliminated to beat the “front runner” and so gain momentum rising towards the actual election. Once elected, the governor often gets in trouble when pandering to any one part of his base--no interest is strong enough to hold off the wrath of the others. Those who have succeeded in the post have done so by being forceful individuals who could articulate their own strong views, whatever those views were, to the most people, as well as being able at dealing with legislators on an individual level. Gov. Leroy Collins stands out as a figure of great interest. First elected in 1955 as the issue of desegregation heated up, he took stands against the pro-segregationists (Dixiecrats) and was able to argue that in Florida racial conflict such as that going on in neighboring states would damage the state’s tourism business and the increasing movement of new people from the north to Florida; the business community responded. Collins spent a good deal of his energy and clout on vetoing measures from the legislature, and essentially held those who opposed integration to a kind of standstill (no public school in Florida was successfully integrated during his tenure as governor, but the state was not plunged into the turmoil of neighboring Alabama and Georgia). But the infighting pulled the previously all-powerful Democratic Party in the state into pieces. He was succeeded by a Republican, Claude Kirk, Jr., in the late 60s. Democrats, still in control of the state legislature, united against Kirk whose term included various debacles from his meddling in busing battles to dubious personal actions. (To fight organized crime in Dade County he “hired the Wackenhut Corporation, a private detective agency, to handle the investigation, instead of the State Bureau of Investigation” and then claimed that the underworld had a price on his head.) All of which helped to hand things back to charismatic Democrat Rueben Askew. One small, irresistible example of their political battle: When Kirk in 1970 called Collins a “mama’s boy,” Askew, in front of an audience in South Miami Beach, said “I just wanted you to know that he is correct, because I love that mama of mine” and got a standing ovation from an audience in which, as he put it, “the vast majority...were Jewish mamas.” Askew swept to victory. Lawton Chiles in the same year came from nowhere to win the Senate seat by walking 1,000 miles across Florida speaking to the grass-roots voters of the state, while television coverage turned him into a household name. Askew, Chiles, and Askew’s successor Bob Graham, admired Collins and learned from him. They understood how to reach out via the media to the people of Florida and to speak across their divisions, to find the common denominators on the personal level. Jeb Bush—the most dominant figure the Republicans had ever had—lost to Chiles in '94, but after softening his image some on issues of race and education, took office in '98 and set about, as he had promised, dismantling much of the state government bureaucracy, undoing the state university Board of Regents and privatizing much of the civil service, while at the same time taking the lead on two issues on which the whole state seems to agree, hurricane preparedness and protecting the Everglades. All through these years, below the gubernatorial level, local and legislature elections showed an inexorable shift to the Republicans (helped by a court ruling forcing redistricting in the late 1960s to unlock the Democrats’ control). This, and waves of arrivals, from the Midwest, from the Northeast, from Cuba and then from the Caribbean and Latin American, bring us to the point where the book reaches its natural climax, our category 5 political hurricane, the Presidential election of 2000. Whole books—among them Jeffrey Toobin’s Too Close to Call and Julian Pleasants’ Hanging Chads—have been written about this event alone, but Colburn concentrates on how this spectacle resulted from the political state of the state. The splits in parties and partisanship play out, as does the way the state had grouped into distinct political bastions of the like-minded, so that the Palm Beach “Butterfly Ballot" alone undoubtedly changed the result of the election, in a way that might not have been true somewhere where the political groups were more thoroughly shuffled. The change (made in the late '90s) from having a powerful set of elected members of the governor’s cabinet to just a few, with the other positions becoming gubernatorial appointments, gave us Secretary of State Katherine Harris (whose ignorance of the election laws was matched by the partisanship and ineptitude of many, on both sides, at lower levels), a State Supreme Court largely made up of Chiles appointees, and a State Legislature now majority Republican and eager to wind things up in Bush's brother’s favor. One small correction that should be made: In 2000 when the absentee ballots from the military became an issue we were not, as the author says, at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s been a long war, but not that long—and the course of the wars of this decade are in part the result of what happened in those few weeks after election day. In his acknowledgments, the author thanks a succession of people who offered advice in making his book more readable and conveying the story, and I thank them, too. Colburn clearly knows lots about demographics, but the book is accessible, the prose and points vivid, even to this non-wonk. The book ends with the election of 2006, which is covered briefly, concentrating mainly on Charlie Crist becoming governor. (Here at FBR we await with interest Congresswoman and 2006 Senatorial-candidate Katherine Harris’s promised memoir, and where is the book on Mark Foley?) One lesson for the future is clear. While the book speaks of yellow, blue and red, we are purple, with the fulcrum of our seesaw now the I-4 corridor across the middle of the state: new people moving into and around Orlando are mixed in age, race, and ethnicity and their votes are unpredictable. We have one Republican and one Democratic Senator, and a Republican governor who soon after taking office made clear that we need voting machines as reliable and verifiable as our gas pumps and automated tellers. We in Florida know that every vote counts. Everyone who leaves the state (don’t you know someone who has taken a vote to the mountains of North Carolina or Tennessee?) matters. And so, most importantly, does each new voter, whether young Floridians coming of age here, fresh arrivals from Minneapolis or Mississippi, or newly-made citizens from Peru. Few know or understand the state’s history; books like this should be required reading. Lynne Barrett is Editor of The Florida Book Review. |

|

Write-In: Diary of a Congressional Candidate in Florida's Fourth Congressional District by Richard Grayson

(Dumbo Books, Paperback, 105 pp., $9.95) Interview by Tom DeMarchi |

Tom DeMarchi interviews Richard Grayson, author of Write-In: Diary of a Congressional Candidate in Florida’s Fourth Congressional District

In 2004, fiction writer Richard Grayson campaigned as the Democratic write-in candidate against incumbent Republican Ander Crenshaw for Florida’s 4th Congressional District, a move roughly akin to Harvey Fierstein crank calling Evander Holyfield for the Heavyweight Boxing Title. (In the end, Crenshaw received 255,448 votes; Grayson received 1,167.) Grayson’s hilarious, informative account of his 2004 campaign first appeared as a blog on McSweeneys.net. In 2007, Grayson compiled his blog entries and published them as Write-In: Diary of a Congressional Candidate in Florida’s Fourth Congressional District, through his own press, Dumbo Books. He plans on publishing books by other authors later this year. Write-In might be a collected blog, but it unfolds like much of Grayson’s fiction. On display we find suspense, humor, self-mockery, absurdity, telling details, deep knowledge of the subject matter, and a narrative voice informed by humility, fierce intelligence, and compassion. It makes you wonder what Grayson could accomplish if he took his campaign more seriously. Grayson has campaigned for Congressional office multiple times. A lifelong political activist, he’s currently running as the Democrat against incumbent Republican Jeff Flake for Arizona’s 6th Congressional District. Florida Book Review: Are you a fiction writer who campaigns or a candidate who writes fiction? Richard Grayson: Yes. FBR: Throughout Write-In you admit that your chances of winning are slim and none. Your chances against Flake are equally bad. Why invest so much time, money and energy toward running in unwinnable races? RG: For the same reason I write books of short stories that are unwinnable in the marketplace, I guess. Because I enjoy doing it. But I really believe that contested elections are important in a democracy. One of the reasons we tend to have a partisan war with hysterics on both sides in Congress is that the vast majority of districts are safe seats. I testified at the state commission that did the redistricting in 1991, following the 1990 census, when they met in Gainesville. Karen Thurman, the current Democratic party state chair, was on that commission, and surprise, one of the districts created was one that centered around her state senate district and she got elected to Congress (a seat she lost after the 2000 redistricting). The Ocala Star-Banner, Orlando Sentinel and Gainesville Sun ran stories on my testimony. I showed some drawings I'd made of my proposed districts. For the Orlando area, I'd created a Congressional district in the shape of Mickey Mouse ears. For Brevard County and the Space Coast, my district was shaped like a rocket ship. I had a gator-shaped district centered around Gainesville and a palm-tree-shaped district in Palm Beach County. I was in my first semester of law school, and one of the members of the redistricting commission, former House speaker Jon Mills, director of UF Law's Center for Governmental Responsibility, asked for my drawings so that they could have them for the official record. Three years later, Jon became my boss when I went to work as a staff attorney at CGR, but he made sure he kept me out of any work we did on the electoral process! John Anderson, whom I voted for in the November 1980 election for President—the only time since 1972 I didn't vote for a Democrat—and whom I mention in my book, is now a Nova Southeastern law professor whom I got to know during my four years as an administrator at the law school. John has studied the issue with colleagues, and they've done some brilliant scholarly writing on the problem of the gerrymandering that has turned the vast majority of U.S. House seats "unwinnable," as you say, for one party or the other. He's also proposed several innovative solutions that work in other nations, such as multi-member districts (which we used to have in the Florida legislature when I moved to the state in 1980) and preference voting. It annoyed me that so many Florida incumbents in Congress were "elected" on that day in May when they filed for reelection and no one bothered to oppose them. In 2002, living in Davie, I got a ballot I had gotten several times in the past: there's not even a spot for the U.S. House race. You'd think at least you could vote for the incumbent or not vote for him or her. But Florida doesn't do that, and I find it sad. As a hopeless candidate, I don't have to worry about fundraising, currying favor with anyone or avoiding saying what I think for fear of losing votes. It's an ideal situation in many ways. FBR: You open Write-In with a frightening statistic: "Over 90 percent of Americans live in congressional districts that are essentially one-party monopolies." These monopolies are maintained though a variety of tactics and conditions: redistricting, voter apathy, and patronage, among others. How do parties establish these monopolies in the first place? RG: Through the redistricting process, which is first and foremost incumbent protection and sometimes ridiculously partisan. I recall being in Fort Worth in 2003 while Tom DeLay was getting the Texas legislature to redistrict the Congressional seats in a naked Republican power grab. The Democratic legislators fled to Oklahoma and New Mexico to avoid the vote, but they couldn't do it forever and the GOP could gerrymander state to create several more Republican safe seats Of course Tom DeLay's own seat wasn't safe after he was indicted on corruption charges. FBR: One of Write-In's real triumphs is your humorous handling of the surveys you received from all those special interest groups and organizations. When the first one landed in your mailbox—from Gun Owners of America—you wrote, "Surveys from interest groups are fun to fill out and can help the campaign." Within two months "questionnaires [were] coming in at a rate of about one a day," many of them exhaustive and tedious. Right-leaning Eagle Forum, a group that opposes same-sex marriage (their website's mission statement proclaims "We support constitutional amendments and federal and state legislation to protect the institution of marriage and the equally important roles of father and mother," and “Eagle Forum successfully led the ten-year battle to defeat the misnamed Equal Rights Amendment with its hidden agenda of tax-funded abortions and same-sex marriages") bludgeoned you with 69 questions; when their final question asked you to describe how you'd "support traditional marriage," you answered, "Kill Liza Minelli." Why is same-sex marriage such a polarizing issue? RG: I think it's fading a bit. In 2006, Arizona became the first state to vote against an anti-same-sex-marriage amendment to the state constitution after that issue seemed to work everywhere else. I was shocked last month when Jeff Flake, the very conservative Arizona Republican I'm now running against—someone with a very poor record on gay rights (organizations like the survey-happy ones you mention but on the left, like Human Rights Campaign, had consistently rated him a zero based on his votes)—ended up as one of the 35 GOP House members to vote for ENDA, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act. Flake, a religious Mormon, said it was the hateful rhetoric against gay people that made him inclined to vote for the bill. Now, I happen to be one of those happily single people who, like Ralph Nader, believe that same-sex marriage is a crafty plot to force us all of into matrimony and couplehood. I was 18 and hanging out in Greenwich Village the summer of 1969 during the Stonewall riots, and to some of us back then, the only advantage of being gay was that you couldn't get married. But I support choice, and there are really good policy reasons that we need same-sex marriage. Teaching in a religious high school a couple of years ago in Phoenix, I discovered that just about all the kids, including the kind of straight jocks you'd think would be very homophobic, just couldn't understand why there isn't same-sex marriage yet. This issue will eventually fade as an electoral hot-button; right now people are more interested in demonizing immigrants. FBR: Which presidential candidate do you support for '08, and why? Who do you think has the best chance of winning? RG: I have no preferences among the Democrats. Due to a staff mix-up, I am actually listed as a candidate for President in the February 5 Arizona presidential preference primary: I'm where I was back in 1988, when I headed a political committee called Florida Democrats for Undecided. In the Florida primary that year, "uncommitted" was listed along with Michael Dukakis, Paul Tsongas, Jesse Jackson and the other candidates, and I was one of those championing the unsure and the uncaring. I got publicity in the Florida Times-Union and other state papers and got on several radio shows, like Debbie Elliott's show on WNWS in Miami. I think 2008 will be a Democratic year no matter who the presidential nominee is. FBR: You've been politically active since you were a teenager in the 1960s. What first sparked your interest in politics? RG: My parents and grandparents talked about it a lot, I guess. My grandfather Herb Sarrett had been a big supporter of Eugene V. Debs, the five-time Socialist candidate for President. I just found politics interesting. When I was in kindergarten, I wore a Stevenson/Kefauver button with pictures of the Democratic candidates. Elections seemed like a lot of fun. Despite its ostensible serious concerns, politics is basically a comic enterprise. FBR: I was born in 1969, so my sense of an author's cultural influence might be highly romantic, but it seems that during the sixties an author's political perspective mattered on a broader level than it does today, particularly to college students. I don't think it's a coincidence that Kurt Vonnegut was one of the best-selling authors on college campuses during the late sixties and early seventies. It's doubtful that Slaughterhouse-Five influenced Melvin Laird's policies, but Vonnegut's anti-war message spoke directly to a large segment of the population. Mainstream journalists went to people like Vonnegut, Mailer and Heller for statements about the Vietnam War. Many outspoken authors were, I think, household names, literary celebrities, even to casual readers, the way David Sedaris and J.K. Rowling are today. Rowling has a huge cultural influence—the cape industry is booming, kids are chowing down booger-flavored jellybeans, fundamentalist campers roast marshmallows over burning copies of Order of the Phoenix, etc—but I can't imagine Time asking her or Sedaris to offer a perspective on Iraq. And if Time did ask, I wonder whether readers would notice or care. Did the era of best-selling-author-as-motivating-activist ever actually exist? If so, what factors have led to its demise? RG: Probably the same cultural factors that have made serious literature a marginal enterprise. We do have celebrities testifying before Congress, leading antiwar rallies, taking up causes—but they are all performers, since nobody but other writers know who leading authors are. The closest thing now is Obama backer Oprah Winfrey, who is important in literary circles because her Book Club can move a lot of units—the term younger writers in New York now use for what we used to call books. The writer-as-candidate was less unusual in the 1960s: James A. Michener and Gore Vidal ran for Congress; Mailer and William F. Buckley ran for mayor in New York. I loved Vonnegut from the afternoon when I was 16 and picked up a copy of Cat's Cradle at the Walt Whitman Shopping Center in Huntington, Long Island, but it had nothing to do with politics. I don't recall him being political. To be honest, I went to probably a hundred antiwar rallies and can't really remember any writers speaking. I didn't go to the Pentagon in 1967, but Mailer's The Armies of the Night is one of my favorite books, one I've enjoyed teaching. Today nobody cares what fiction writers or poets or playwrights think about politics...or anything else. Arthur Miller is dead. FBR: Has your activism informed your fiction writing? RG: I wouldn't think so. But it has taken time from my production of short stories, so it's been a boon to lovers of good literature all over the United States. I can perform a civic service and please discerning readers of fiction at the same time. FBR: Between a crushing teaching load (seven classes!), campaigning, and blogging regularly, where do you find time to write fiction? RG: Well, the seven classes was a one-time thing, and I'll hardly be teaching much in 2008. But I write fiction only when I enjoy it. I wrote a lot of stories in the fall of 2004, when I was running the campaign in Write-In, had a job as associate director of student services at Nova Southeastern University's Shepard Broad Law Center and taught two undergrad classes at night. Right now I've stopped writing fiction with no plans to go back to it. My last couple of books got some nice notices, but they didn't sell many copies—to put it mildly!—and, as at other times in my fiction writing "career," usually after a book comes out, I get discouraged and decide that nobody's interested. I did not write any fiction for years at a stretch—for example, between 1991 and 1994, when I was studying at UF law school and beginning my faculty job there, and most recently between 2001 and 2003, my first years on the job as director of academic resources at NSU Law before I took a lesser position that freed up my time. There's no point in writing fiction unless it gives me pleasure. For now, I don't have anything to say in the genre. With almost 300 published stories and a bunch of books, I've probably written enough bad fiction for this lifetime—as some perceptive critics have suggested. That said, I probably will one day decide to write another story. FBR: What unique political challenges did Florida face in 2004 that it still faces in 2008? RG: Probably there are more challenges now. In 2004 the economy was good and growth was still vibrant. At the Center for Governmental Responsibility back when I worked there, Jon Mills and other and the state's other policy institutes were working on how to manage the phenomenal growth. But in the year ending July 1, 2006, Florida slipped to the 19th-fastest growing state, a huge drop from the 9th-fastest growing the previous year. Retirees now are more likely to head for the Southwest, Georgia or the Carolinas. The insurance cost crisis didn't exist in 2004. With the mortgage crisis and housing industry in a recession, Florida's can't rely on growth anymore. There are other problems. Florida's educational system never really caught up; I remember Gov. Bob Graham's goal from the early 1980s of getting us into the top quartile of states in education spending, but Florida never made it. My own feeling is that the constitutional bar to a state income tax has been a real detriment to Florida—I once headed a state political action committee called Floridians for a Personal Income Tax that went nowhere. But the weather's great and Florida is breathtakingly beautiful. That's why I plan to buy a condo in a Sunrise senior citizen community now that I'm age-eligible. If you want to follow Richard Grayson’s current Congressional campaign, visit his blog. For more information on Grayson’s 2004 Congressional campaign, fiction writing, astrological sign, favorite musicians and movies, and to see how much he has in common with Spiderman, visit: http://www.myspace.com/Richard_Grayson or http://www.richardgrayson.com/ Tom DeMarchi, Director of the Sanibel Writers Conference, lives and votes in Fort Myers, Florida. |