FBR Feature: Elizabeth Bishop

“Should we have stayed at home,

Wherever that may be?”

Social Distancing, a Return Home, and Elizabeth Bishop’s “Questions of Travel”

by Freesia McKee

Wherever that may be?”

Social Distancing, a Return Home, and Elizabeth Bishop’s “Questions of Travel”

by Freesia McKee

|

Elizabeth Bishop: Poems, Prose, and Letters

Library of America, 2008 Elizabeth Bishop The Complete Poems 1927-1979 Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1983 |

If there is one thing that this pandemic has taught my literary self, it is that there is no lack of creative writing on the topic of loneliness. “All poetry is about longing,” my undergraduate poetry professor opined. On my morning walk the other day, “One Art,” which is perhaps Elizabeth Bishop’s most famous poem, floated into my consciousness. And it made me cry because the poem is a love song to loss. We are living in a lonely era in which we need love songs. Bishop’s speaker possesses a deep and knowing calmness as she delivers imperatives to the reader: “Lose something every day. Accept the fluster…”

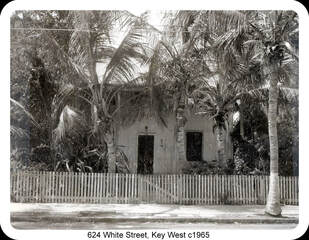

If you’ve read only one Bishop poem, it’s probably “One Art.” Lots of us first encounter the poem in literature survey courses or high school classrooms. Remember the opening? “The art of losing isn’t hard to master…” I read the line as a tongue-in-cheek quip, but also a treatise on the illusion of control, something the pandemic teaches us we possess so little of. As a child, Bishop lost her parents to illness and institutionalization. She moved a lot, and there is an acute sense in her work of the search for home. Bishop wrote most of her first book, North and South, while she lived in Key West for ten years in the nineteen-thirties and forties. Afterwards, Bishop moved away to Brazil. Bishop’s long-time lover Lota de Macedo Soares killed herself in 1967. And Bishop lived her life as a lesbian in the closet, which is another kind of loneliness, a persistent and existential kind of social isolation.

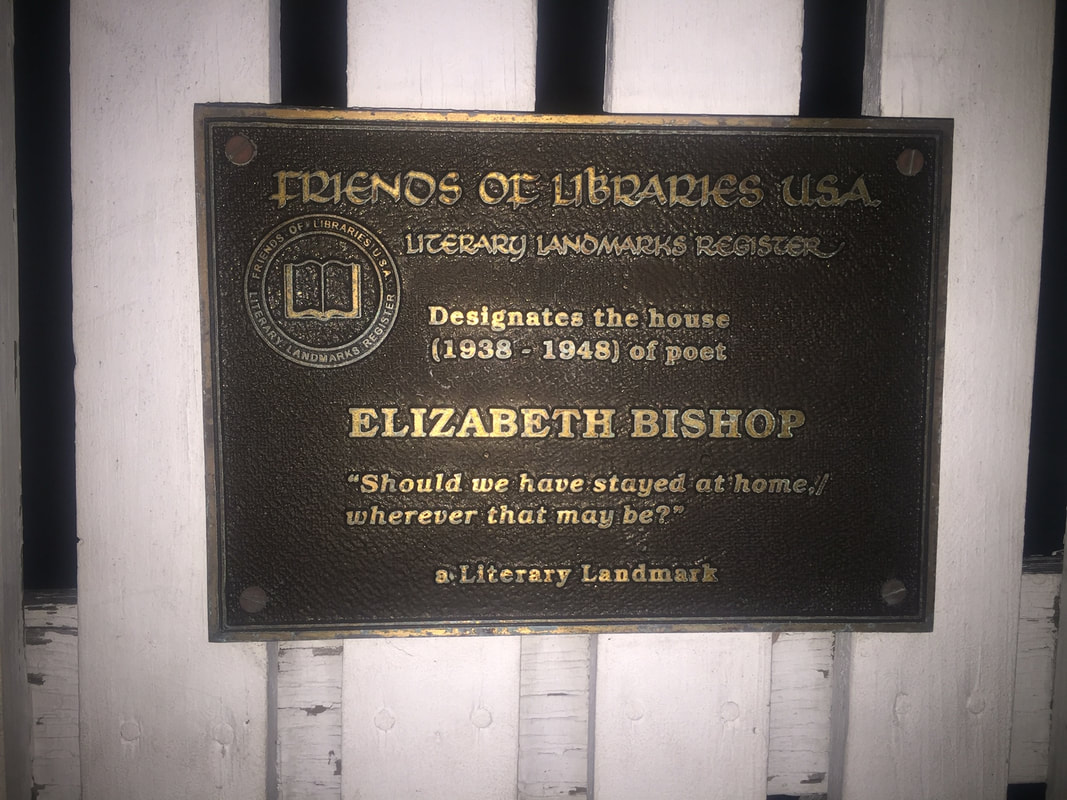

Friends of Libraries USA

Literary Landmarks Register Designates the house (1938-1948) of poet ELIZABETH BISHOP “Should we have stayed at home,/ wherever that may be?” A LITERARY LANDMARK

|

“Think of the long trip home,” Bishop writes in "Questions of Travel," the same poem from which the lines on the old plaque were sampled. "Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?/ Where should we be today?”

“Questions of Travel” ends with a “traveller” who “takes a notebook.” We see what she is writing in this notebook in the last two stanzas of this poem-within-a-poem:

“Questions of Travel” ends with a “traveller” who “takes a notebook.” We see what she is writing in this notebook in the last two stanzas of this poem-within-a-poem:

Is it lack of imagination that makes us come

to imagined places, not just stay at home?

Or could Pascal have been not entirely right

about just sitting quietly in one's room?

Referencing Blaise Pascal's 1654 maxim, "All of humanity's problems stem from man's inability to sit quietyly in a room alone," Bishop taps into a timeless tension. Do I stay or do I go? Where do I find the answers? And, now that I've gone loking and still haven't found what I need, where do I go next? Do I go back home? Where is home?

Here, two other thinkers bubble up from my own canonical education. Seneca wrote in his Letters to a Stoic, “You must lay aside the burdens of the mind; until you do this, no place will satisfy you.” Rilke wrote in Letters to a Young Poet, “Believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance, and have faith that in this love there is a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it.”

In this tradition, "Questions of Travel" is also, in a way, also, in a way, a kind of letter. The “traveller” in the poem continues to write to us:

Here, two other thinkers bubble up from my own canonical education. Seneca wrote in his Letters to a Stoic, “You must lay aside the burdens of the mind; until you do this, no place will satisfy you.” Rilke wrote in Letters to a Young Poet, “Believe in a love that is being stored up for you like an inheritance, and have faith that in this love there is a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it.”

In this tradition, "Questions of Travel" is also, in a way, also, in a way, a kind of letter. The “traveller” in the poem continues to write to us:

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there . . . No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?

The choice is never wide and never free.” I have been struggling in these times of social distancing with facing my own inner demons, my fears and my inadequacies and my guilt and my contempt. This confrontation happens during the quietest moments, like on my morning walks with my dog Merlin in North Miami. In the quiet, the choice is “never free,” but it is always worth it.

*

Anyone who’s tried to meditate—or just slow down—is familiar with the excruciating experience of turning inward. The things we spend our energy avoiding are suddenly right there, surfacing. When we practice social distancing, we are “losing farther, losing faster” the physical possibilities of how we might distract ourselves each day. For those of us who have lost our jobs or are working from home, our to-do lists shrink down to our immediate sphere. Even if our online presence makes us feel grander than we really are, the reality of our homes may, to return to "Questions of Travel," start to “look like the hulls of capsized ships, / slime-hung and barnacled.” Right here are the four walls of our fears, the closed doors of our plans, the ceilings of our inner capabilities.

Many people have lost access to their workplaces, spots for public socializing, the welcoming homes of friends, even car time spent during daily commutes, and so more time at home cracks open the illusion of distraction for each of us. We gain (sometimes terrifying) interior space that we may never have quite realized we cordoned off. Even if we still feel busy (I do), our roles as literal travelers are now limited.

In “Questions of Travel,” Bishop writes, “What childishness is it that while there’s a breath of life / in our bodies, we are determined to rush / to see the sun the other way around?” To stop rushing isn’t what most of us seek. We’re afraid of the sensation of boredom, some of us are fixated on illusions of accomplishment and legacy, and we’re scared of what will happen when we aren’t busy anymore.

I want to argue that slowing down, if possible, may be an ironic gift, a kind of painful blessing. By social distancing and slowing down, we are saving each other’s lives. And deliberation also happened to be what made Bishop a great artist, polishing her exquisite oeuvre with finer and finer grades of sandpaper. Not an electric sander, but handiwork. I’m not saying that we should put pressure on ourselves to write Bishop-level poems right now, nor that we need to coerce ourselves into creative production during this time of collective trauma, but just that this distance we are experiencing (this grief, this slowness, this alteration) might provide us with mental and spiritual opportunities.

"Questions of Travel" continues: “Oh, must we dream our dreams / and have them, too?” Nightmares about getting sick, curious memory-dreams of big social gatherings, intense worry about loved ones that manifests somatically through lack of sleep or not being able to wake up in the morning: Yes, indeed, like Bishop, we are being forced to have our dreams and dream them, too.

Many people have lost access to their workplaces, spots for public socializing, the welcoming homes of friends, even car time spent during daily commutes, and so more time at home cracks open the illusion of distraction for each of us. We gain (sometimes terrifying) interior space that we may never have quite realized we cordoned off. Even if we still feel busy (I do), our roles as literal travelers are now limited.

In “Questions of Travel,” Bishop writes, “What childishness is it that while there’s a breath of life / in our bodies, we are determined to rush / to see the sun the other way around?” To stop rushing isn’t what most of us seek. We’re afraid of the sensation of boredom, some of us are fixated on illusions of accomplishment and legacy, and we’re scared of what will happen when we aren’t busy anymore.

I want to argue that slowing down, if possible, may be an ironic gift, a kind of painful blessing. By social distancing and slowing down, we are saving each other’s lives. And deliberation also happened to be what made Bishop a great artist, polishing her exquisite oeuvre with finer and finer grades of sandpaper. Not an electric sander, but handiwork. I’m not saying that we should put pressure on ourselves to write Bishop-level poems right now, nor that we need to coerce ourselves into creative production during this time of collective trauma, but just that this distance we are experiencing (this grief, this slowness, this alteration) might provide us with mental and spiritual opportunities.

"Questions of Travel" continues: “Oh, must we dream our dreams / and have them, too?” Nightmares about getting sick, curious memory-dreams of big social gatherings, intense worry about loved ones that manifests somatically through lack of sleep or not being able to wake up in the morning: Yes, indeed, like Bishop, we are being forced to have our dreams and dream them, too.

*

You who are reading this, dream with me. Because I am in the land of my imagination more than usual these days, I have a vision of traveling back to stock Island and bicycling to Bishop's home in Key West. The Literary Seminar will have put together another week of Bishop-themed events, again taking place in her house, this time singularly focused on Bishop’s notions of home. We will be sitting in a room full of other poets, every seat filled. We will be listening to a live lecture. After the lecture, we will shake hands with the presenter. Or, maybe, we will ask if we can hug her for the hell of it. Why? Gathering our lonely selves together will have become "the long trip home."

Freesia McKee is author of the chapbook How Distant the City (Headmistress Press, 2018). Her words have appeared in Flyway, Bone Bouquet, So to Speak, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Virga, Painted Bride Quarterly, CALYX, About Place Journal, and the Ms. Magazine Blog. Freesia is a staff book reviewer for South Florida Poetry Journal. Her reviews have also appeared in TQ Reviews, Pleiades Book Review, Gulf Stream, and The Drunken Odyssey. Freesia was the winner of CutBank Literary Journal’s 2018 Patricia Goedicke Prize, chosen by Sarah Vap. Learn more at her website.

Freesia McKee is author of the chapbook How Distant the City (Headmistress Press, 2018). Her words have appeared in Flyway, Bone Bouquet, So to Speak, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Virga, Painted Bride Quarterly, CALYX, About Place Journal, and the Ms. Magazine Blog. Freesia is a staff book reviewer for South Florida Poetry Journal. Her reviews have also appeared in TQ Reviews, Pleiades Book Review, Gulf Stream, and The Drunken Odyssey. Freesia was the winner of CutBank Literary Journal’s 2018 Patricia Goedicke Prize, chosen by Sarah Vap. Learn more at her website.